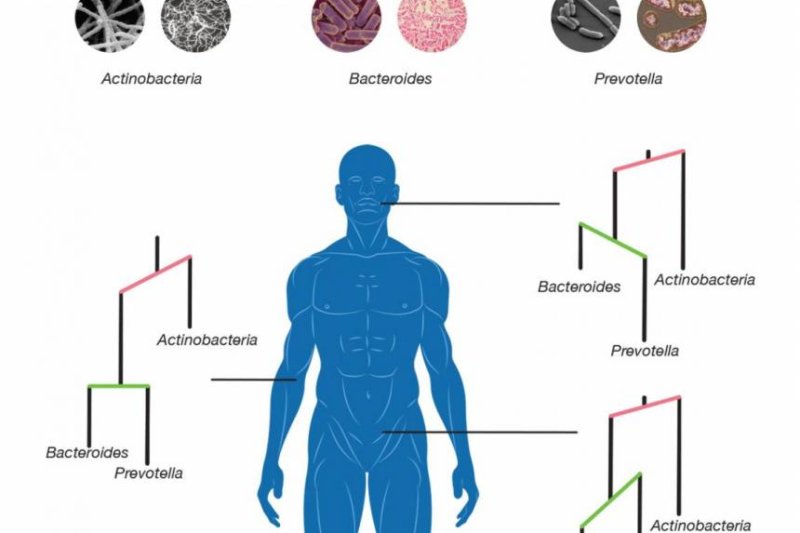

New statistical modeling tools allowed scientists to track the evolution of microbe species in different parts of the human body. Photo by Jonathan Fuller/Duke University

March 20 (UPI) -- Different microbes specialize in colonizing different parts of the human body. New research by Duke scientists shows microbes diverged into new species as they adapted to new organs and body parts -- including mouths, noses, genitalia and guts.

"Over the last decade, there has been significant interest in developing probiotics and transplants of beneficial bacteria to treat a wide variety of health issues," Lawrence A. David, an assistant professor of molecular genetics and microbiology at Duke's School of Medicine, said in a news release. "Our analysis gives us a window into how different bacteria adapt and evolve so that we can more effectively predict which implanted species will survive to make an impact on disease."

A growing body of research has made it increasingly clear microbes play an important and long-unappreciated role in many facets of human health. But understanding how microbes evolved to thrive within a variety of human biological systems -- from the brain to the digestive tract -- has proven difficult.

One of the main problems is measuring how shifts in the abundance of one bacterial species affects others. Researchers at Duke developed a solution to the problem using a model typically deployed for the analysis of mineral ratios within rocks.

Researchers populated their model with microbiota sequencing data as well as information on each species' position within their family tree.

As researchers explained in their paper, the strategy "combines statistical and phylogenetic models to overcome compositional data challenges and enable evolutionary insights relevant to microbial communities."

Their statistical simulations showed how changes in bacteria abundance influenced the evolution of microbes in different parts of the body.

"This technique unlocks a tremendous toolbox of statistical methods that wouldn't have worked before, but that can now be used to analyze microbiome data," said Justin Silverman, a doctoral student in David's lab.

David and Silverman used their new statistical tools to analyze bacterial sequencing data from the Human Microbiome Project. They found one group of streptococci bacteria only recently diverged from its relatives, branching species specifically adapted to various parts of the mouth -- the palate, tongue, throat, tonsils, gums and plaque.

Researchers hope their findings, detailed in the journal eLife, will inspire new microbial therapies for human health problems.