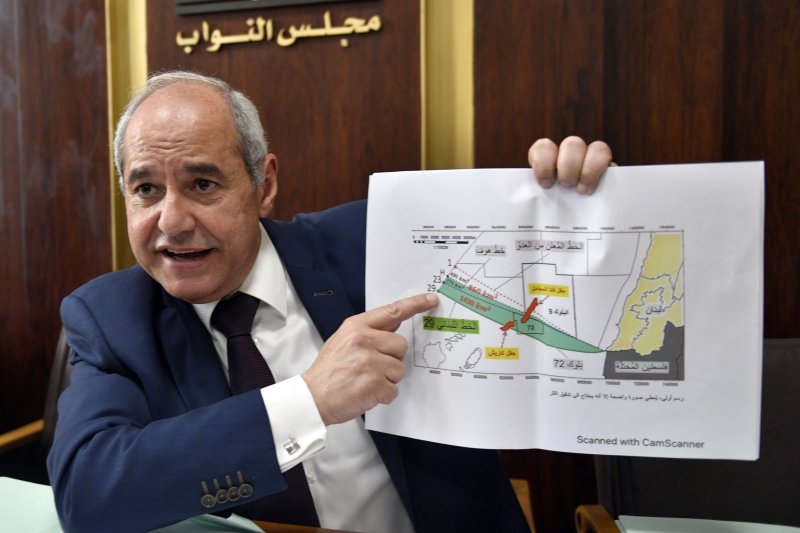

Member of the Parliament Melhem Khalaf shows a map of Line 29 at the Lebanese Parliament building in downtown Beirut on June 6. He said Israel began drilling for oil in some fields, including those adjacent to the Lebanese border. Photo by Wael Hamzeh/EPA-EFE

BEIRUT, Lebanon, June 24 (UPI) -- Europe's growing need for gas caused by Russia's war on Ukraine is increasing interest in speeding exploration and drilling of gas fields in the Mediterranean Sea -- and pushing Lebanon and Israel to try settle their years-long maritime border dispute.

The arrival of a floating gas exploration ship, operated by London-based Energean, to the Karish field off the Mediterranean coast earlier this month has revived the dispute and raised tension between the two countries, which are still in a state of war.

The Karish field, which contains 1.4 trillion cubic feet of proved and probable gas reserves, is located south of the southern boundary of the disputed area.

The rising tension prompted the Lebanese government to call for stopping Israel's exploration efforts and to ask Amos Hochstein, an American who has been mediating indirect talks since 2020, to intervene.

In a recent turn of events, Lebanon presented a new "more realistic" offer to Hochstein, a senior adviser for energy security at the U.S. State Department, during his visit to Beirut last week, an official source told UPI on the condition of anonymity.

"It is clear that it [demands] more than Line 23 and backed away from Line 29, which it considered as the negotiation line," said the source, who has been involved in the negotiations for years.

Last year, the Lebanese delegation to the talks, made up of Army generals and experts, presented a new map that would add 550 square miles (referred to as line 29) to the disputed 330 square mile area (referred to as line 23) of the Mediterranean Sea that each side claims is within their own exclusive economic zones. The negotiations stopped while Lebanon never officially claimed Line 29, which would give it part of the Karish field.

Debt-stricken Lebanon, which hopes to enter the club of oil producers, has wasted almost a decade adopting different delimitation methods and negotiation tactics. Israel, meanwhile, has developed offshore natural gas rigs and started exploration activity outside the disputed area, which is potentially rich in oil and gas and that both countries claim.

Lebanon, the source said, is waiting for Hochstein to come back with Israel's reply to its new proposal, which would give the Karish field to Israel and the Qana field to Lebanon.

He emphasized that his country "will never accept, not now nor tomorrow nor next week, that Israel keeps on drilling in an area that they allegedly claim is outside the disputed zone while we cannot do the same in our own area," the Qana field.

A consortium of international companies, Total, ENI and Novatek, were awarded the right to explore in 2018 with the aim to find natural gas, but "have been pressured not to start drilling" in the Qana field, according to the source.

He, however, noted that Hochstein confirmed Israel's gas-drilling rig, stationed in the Karish gas field, is located in Israeli territory and will not pump gas from the disputed area.

That might have, at least temporarily, defused tension that reached "a dangerous level," with Lebanon's heavily armed Iran-backed Hezbollah and Israel exchanging threats over Karish gas drilling, according to the source.

Hezbollah chief Hassan Nasrallah warned that it will not allow Israel to extract gas from the field until negotiations with Lebanon are completed. Israeli Army Chief Aviv Kochavi threatened to respond with "overwhelming force" in any next war with Hezbollah.

It is yet to be seen whether Lebanon's new compromise would open the door for resuming the negotiations and averting confrontation.

But backing away from Line 29 has angered opposition politicians, energy experts and activists in Lebanon.

"Whatever the Lebanese part has proposed to Hochstein, it is not linked in any way possible to a technical or legal basis. We are no longer talking about technical matters, law of the sea or international laws. I don't know what this could be called," Marc Ayoub, an energy researcher affiliated with the American University of Beirut's Issam Fares Institute, told UPI.

Ayoub argued that by getting behind Line 29, Lebanon "has started from a position which is weak because Line 23 has a lots of defaults." It also raised questions about "a political compromise" and what is the "political price for that."

He explained that while the Karish field has been in operation since 2013 and the Qana field not yet explored, "you are comparing a field that will be producing in three months' time to a field that is still prospective."

"We don't know what Qana includes until we drill. There are speculations that it could contain some high prospects of oil and gas. But we don't know how much and whether it will succeed or not," Ayoub said. "We need three to five years to know if there is gas and oil and how much.. and this if they allow the international companies to drill" in Lebanese waters.

By then, Lebanon will be missing great opportunities to join the many gas deals underway in the region accentuated by the Ukraine war and Europe's needs for gas supplies.

In fact, it won't be in Israel's interest to reject Lebanon's offer if it wants to develop Karish and increase its gas production. Earlier this month, Israel, Egypt and the European Union signed a memorandum of understanding to export Israel's natural gas to EU countries, which are trying to reduce dependence on the supply from Russia.

"They [EU officials] are looking for the fields that are already explored and here we are talking about Israel and Egypt," Ayoub said, arguing that pressures are being exerted on Lebanon "for the sake of Israel because no company will start working in Karish without security guarantees and a maritime demarcation line."

With Lebanon's collapsing situation and acute financial crisis, he said, the message is clear: "You will not produce gas unless we say when, with whom and how... One can be weak but can negotiate from a strong position, preserving the minimum of national dignity."

A Beirut-based Western diplomat argued that Israel needs an agreement as much as the Lebanese, saying, "There is an open door."

But would Hezbollah, which previously stated that it will agree on any demarcation line adopted by the Lebanese government, accept such a compromise?

"Let's say it gives Hezbollah an exit strategy to avoid having to resort to options that could spark a war," Riad Kahwaji, a Dubai-based Middle East security and defense analyst who heads the Institute for Near East and Gulf Military Analysis, told UPI.

Kahwaji said Israel is focusing on Iran and is sending clear messages to Hezbollah and Lebanon of adverse consequences if Hezbollah decides to step in to back Iran militarily in case of an Israeli strike on its nuclear facilities or its arms depots in Syria.

"All these threats, although in a way are linked to the gas field-border dispute between Lebanon and Israel, it is not the whole story, it is part of the story," he said.

It is clear, he added, that Hezbollah does not want to provoke a war as it "allowed the Lebanese government, which everybody knows it has a strong influence over it and over the president, to show flexibility and make concessions to the Israelis to try to de-escalate."

Regardless of how the border issue in Lebanon is resolved, Kahwaji said Hezbollah is trying "to delay the inevitable" as much as possible because "it is always hopeful" there could be a nuclear deal reached by Iran, the United States and the Europeans that will prevent any attack from Israel.