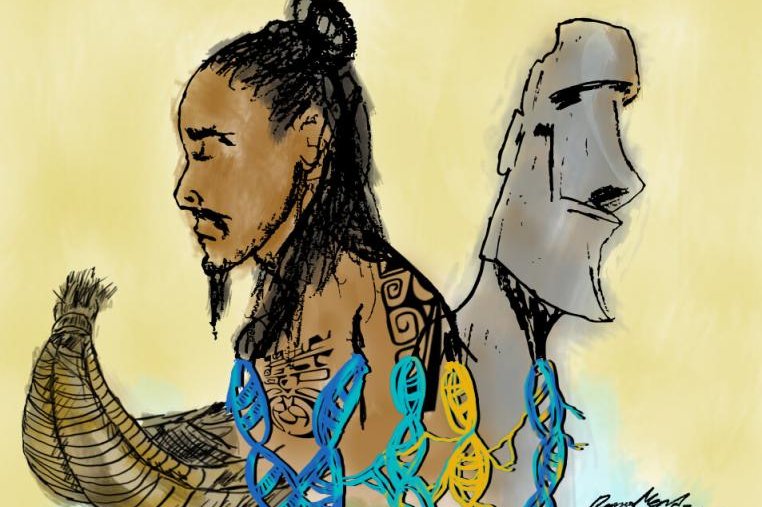

New research suggests ancient Polynesians and Native Americans from what's now Colombia interacted and produced children several hundred years ago. Illustration by Ruben Ramos-Mendoza

July 8 (UPI) -- Ancient Polynesians and Native Americans hailing from what's now Colombia were in contact prior to the arrival of Europeans, according to a new genomic survey.

The topic of precolonial interaction between Polynesians and Native Americans has been debated for several decades.

Proponents of precolonial contact point to a word for a staple crop, the sweet potato, shared by the two groups -- one of several cultural commonalities between Ancient Polynesians and Native Americans.

But critics have argued the two groups weren't capable of navigating the thousands of miles of open ocean that separate the Polynesian islands from South America.

Now, new genetic analysis -- detailed Wednesday in the journal Nature -- suggests the DNA evidence supports those in favor of precolonial contact.

"Genomics is at a stage where it can really make useful contributions to answering some of these open questions," lead study author Alexander Ioannidis said in a news release.

"I think it's really exciting that we, as data scientists and geneticists, are able to contribute in a meaningful way to our understanding of human history," said Ioannidis, a postdoctoral scholar at Stanford University.

After collecting DNA samples from 800 living indigenous inhabitants of Colombia and French Polynesia, researchers surveyed the genomes for evidence of shared ancestry. Scientists were able to trace common genetic signatures -- shared lineage -- between the two groups back several hundred years.

"Our laboratory in Mexico has been very interested in understanding the genetic diversity of populations throughout Latin America and, more generally, of underrepresented populations in genomic research," said Andrés Moreno-Estrada, professor and head of genomic services at the National Laboratory of Genomics for Biodiversity in Mexico.

"Through this research, we wanted to reconstruct the ancestral roots that have shaped the diversity of these populations and answer deep, long-standing questions about the potential contact between Native Americans and Pacific Islanders, connecting two of the most understudied regions of the world."

Before scientists confirmed genetic links between the two indigenous groups, researchers knew that sweet potatoes, first cultivated in South and Central America, also grew in Oceania, which includes the islands of Polynesia.

"The sweet potato is native to the Americas, yet it's also found on islands thousands of miles away," Ioannidis said. "On top of that, the word for sweet potato in Polynesian languages appears to be related to the word used in Indigenous American languages in the Andes."

Although it's possible ships carrying Native Americans might have been blown off course and landed among the Polynesian islands, researchers suspect it's more likely Polynesian ships visited what's now Colombia and carried sweet potatoes back across the Pacific.

However, attempts to investigate the genetic relationships between the sweet potatoes of the Americas and Oceania have yielded inconclusive results. Analysis of ancient DNA from excavated bones have also failed to provide irrefutable evidence of precolonial contact between the two groups.

Now, thanks to modern genomic analysis techniques, researchers were able to trace identical snippets of DNA back to ancestors shared by the two groups. The new analysis suggests the two groups interacted around 1200 A.D., and produced children with both Native American and Polynesian DNA.

"If you think about how history is told for this time period, it's almost always a story of European conquest, and you never really hear about everybody else," Ioannidis said. "I think this work helps piece together those untold stories -- and the fact that it can be brought to light through genetics is very exciting to me."