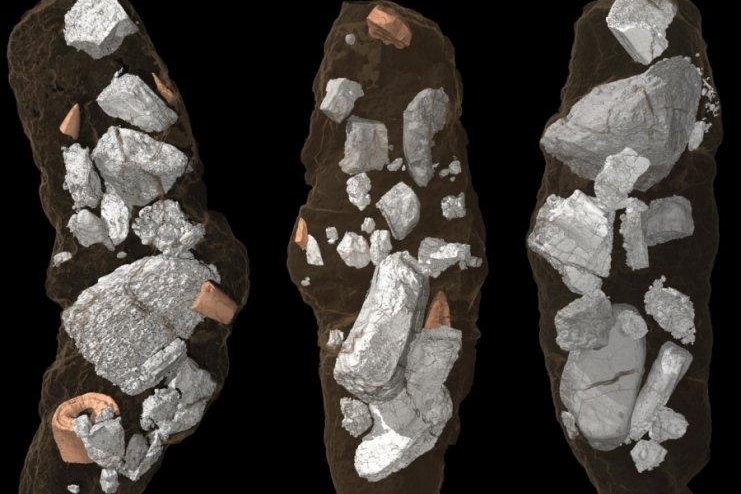

Scientists used advanced imaging to render the structures inside the fossilized archosaur droppings in three dimensions. Photo by Martin Qvarnström/Uppsala University

Jan. 31 (UPI) -- An archosaur species named Smok wawelski was crushing bones 140 million years before the first tyrannosaurids arrived in North America, new research says.

Most dinosaurs used razor-like teeth to rip the flesh from their victims, but tyrannosaurids, including the famed T. rex, sliced flesh and crushed bones. Animal bones offer useful nutrition, including salt and marrow.

Bone-crushing, or osteophagous, the purposeful exploitation of bones, is fairly common among mammals, but rare among dinosaurs and their earliest relatives.

Scientists aren't sure whether Smok wawelski was a dinosaur or dino-like precursor. But thanks to new analysis of a selection of coprolites, or fossil droppings, researchers know Smok wawelski was a bone-crusher, according to a study published Wednesday in the journal Scientific Reports.

Using synchrotron microtomography, imaging technology similar to a CT scan, scientists at Uppsala University in Sweden identified structures within the 210 million-year-old coprolites, including bones belonging to large amphibians and juvenile dicynodonts.

Smok lived during the Late Triassic. The bone-crusher grew to nearly 20 feet in length.

"Smok was a top predator that fed on various prey animals such as temnospondyl amphibians, juvenile dicynodonts, and even fish. So Smok probably ate everything it got its hands -- I mean teeth -- on," Martin Qvarnström, a doctoral student at Uppsala, told UPI. "Some bones in the fossil droppings appear etched but others not. So it appears that the food retention time in Smok differed over time depending on, for example, food type and availability."

Researchers also found the archosaur's teeth in the fossilized droppings, which were unearthed in Poland.

"The typical thin and blade-like teeth of theropods were good for slicing through soft tissue but probably not very useful for crushing bone," Qvarnström said. "The teeth in Smok are quite rounded toward the base, making them slightly more conical in shape and probably more resistant to higher bite forces. But we also know that they were repeatedly crushed, swallowed accidentally, and replaced by new ones."

Though only distantly related and separated by 140 million years, Smok and the tyrannosaurids both featured large heads and broad bodies, the kind of anatomy needed for bone-crushing.

"These large predators thus provide evidence of convergence driven by similar feeding ecology at the beginning and end of the age of dinosaurs," researchers wrote in the study.