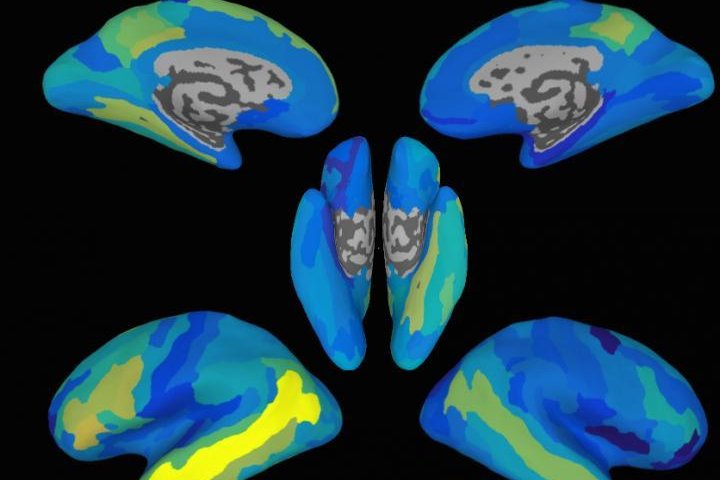

Different words excite different parts of the brain. By monitoring brain activity patterns while study participants silently read sentences, researchers where able to deduce word signatures and predict the brain patterns of newly assembled sentences. Photo by Andrew Anderson/University of Rochester

ROCHESTER, N.Y., Aug. 15 (UPI) -- Neuroscientists are the University of Rochester are taking sentence diagramming to the next level.

For the first time, scientists decoded sentences by analyzing human brain activity, allowing researchers to identify word signatures among brain activity patterns and predict their appearance in different sentences.

Neuroscientists have done a number of studies focusing on the representation of words in the brain, but most have focused on single words. Researchers at Rochester focused on the representation of words within the context of a sentence.

The researchers recruited study participants to silently read dozens of sentences while their brain activity was monitored using functional magnetic resonance imaging.

"Using fMRI data, we wanted to know if given a whole sentence, can we filter out what the brain's representation of a word is -- that is to say, can we break the sentence apart into its word components, then take the components and predict what they would look like in a new sentence," Andrew Anderson, a research fellow at Rochester, explained in a news release.

Fourteen participants read 240 sentences. By analyzing the brain activity pattern for each sentence, researchers were able to dissect specific word representations and predict their future appearance with a success rate of 70 percent.

Researchers further buoyed their semantic model by plotting the sensory, emotional and social context of 242 words. For example, researchers had study participants rate each word or root concept, on a scale of zero to six, for 65 attributes -- including "color," "pleasant," "loud," and "time."

"The strength of association of each word and its attributes allowed us to estimate how its meanings would be represented across the brain using fMRI," said Rajeev Raizada, assistant professor of brain and cognitive sciences at Rochester.

Researchers were able to use this analysis to work backward and predict the patterns of entirely new sentences, using their understanding of the previous sentences and the representations of the aforementioned 242 words.

The findings -- detailed in the journal Cerebral Cortex -- are part of growing body of science illuminating the ways language and meaning are represented in the brain. But there is more illuminating yet to be done.

"Not now, not next year, but this kind of research may eventually help individuals who have problems with producing language, including those who suffer from traumatic brain injuries or stroke," concluded Anderson.