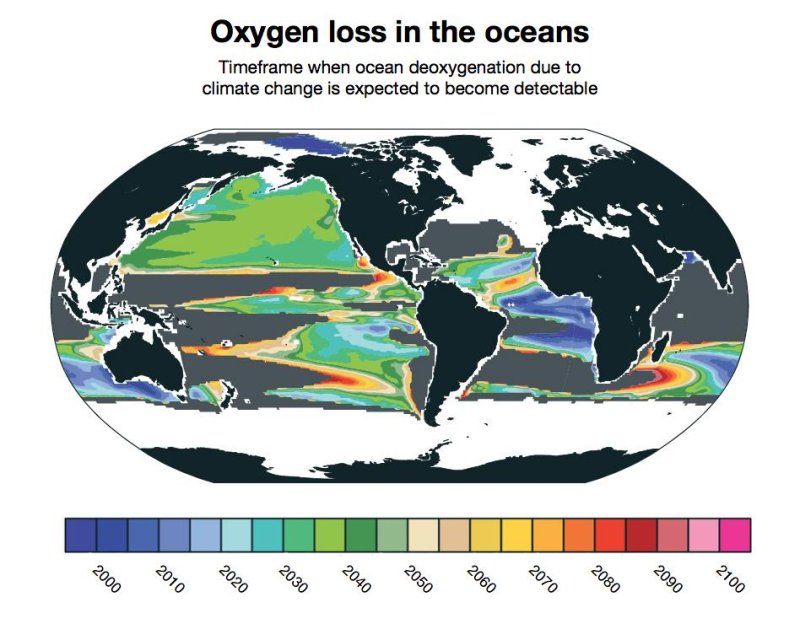

A map shows where deoxgenation caused my climate change will be most severe. Photo by Matt Long/NCAR

BOULDER, Colo., April 27 (UPI) -- Climate models suggest climate change is slowly sapping oxygen from the world's oceans. In some places, declining oxygen levels are already discernible, but in most oceanic regions, scientists struggle to differentiate between climate change-related losses and natural fluctuations.

A new model, developed by researchers at the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, suggests scientists' differentiation difficulties won't last much longer. By the 2030s, oxygen losses caused by climate change will be widespread and readily apparent.

Ocean water gets oxygen both directly from the atmosphere and via photosynthesizing phytoplankton. Its ability to take up oxygen directly from the atmosphere is inhibited as ocean water warms. Warm surface water is less dense and less likely to sink, discouraging mixing and the dispersal of oxygen to lower depths.

Because of natural heating and cooling cycles and complex systems of currents and upwelling, oxygen levels are constantly fluctuating.

To get a better sense of how much fluctuation is natural, researchers ran the NCAR-based Community Earth System Model more than a dozen times for the years 1920 through 2100, making slight manipulations in air temperature inputs each time to account for global warming.

Over time, variability is outstripped by change. The model's evolving outputs allowed scientists to determine whether oxygen-deprived fluctuations are natural or caused by global warming. Patterns of oxygen drain caused by global warming first became apparent during the models run for 2030.

The phenomenon could make it harder for many marine species to breathe, as well as encourage larger dead zones where no marine life can survive.

Researchers published their findings in the journal Global Biogeochemical Cycles.

"We need comprehensive and sustained observations of what's going on in the ocean to compare with what we're learning from our models and to understand the full impact of a changing climate," NCAR scientist Matthew Long, the study's lead author, said in a news release.