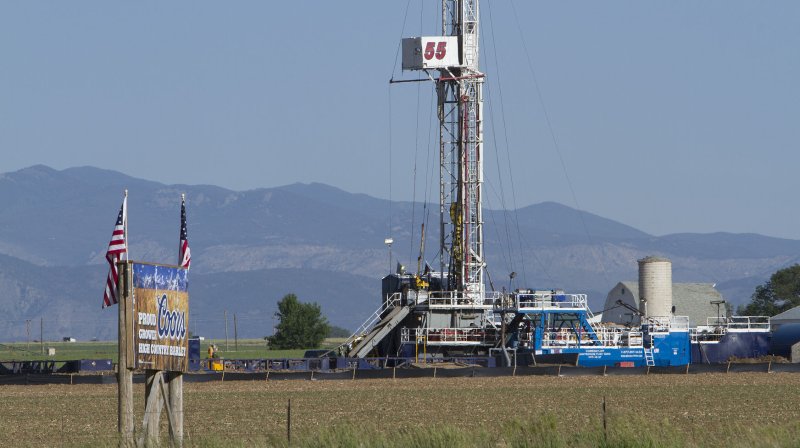

An oil rig stands on farmland that grows barley for Coors Brewery at the Niobrara oil shale formation in Weld County, North eastern Colorado on May 30, 2012. Gas and oil companies are using large amounts of water to obtain shale oil and gas in a process called hydraulic fracturing or fracking. UPI/Gary C. Caskey |

License Photo

Protesters gathered outside the Democratic Governors' Association meeting in Aspen, Colo., over the weekend to protest Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper's support of hydraulic fracturing.

The Protect Our Colorado protesters chanted and waved signs outside the St. Regis hotel, where governors from across the country gathered to discuss political strategies for the 2014 midterm elections.

Hickenlooper has supported the method, known as fracking, of injecting water, sand and chemicals into rock at high pressures to release fuel, and said nearly all of Colorado's oil wells use the process.

Protesters said fracking poses health risks for those who live nearby the wells, because it allegedly provokes air and water pollution that can lead to increased cancer incidence and other health problems.

“This is polluting the water, polluting the air,” said Xiuhtezcatl Martinez, a leader of Earth Guardians, an environmental youth group. “It’s making animals and people sick."

"It’s really scary knowing if you live close enough to a well you can get really sick," Martinez said. "You can have nosebleeds or headaches or blackouts, and it can build up to worse stuff like lung cancer.”

Others appealed to the governor to hear citizen concerns.

"We want the governor to know that fracking is very unpopular with people,” said Micah Parkin, who helped organize the protest. “There is a ground swell of parents and youth and people across not only Colorado but our whole nation that are very concerned with fracking, and we want to see it stopped until it can be proven safe.”

In addition to localized health risks, new research seemed to confirm concerns fracking weakens the ground and becomes vulnerable to seismic activity. The study found fracking sites saw an increase of "earthquake clusters" triggered by seismic movement far away.

A spokeswoman for Energy In Depth, an industry-run outreach program through the Independent Petroleum Association of America, dismissed the protesters concerns, citing strong support for the method from state and national leaders.

“These activists are staking out a fringe position that’s been rejected by Democrats across the country," said Courtney Loper, Mountain States field director for Energy in Depth, in an emailed statement.

Support for fracking, she said, comes "from state legislators to governors to members of President Obama’s cabinet, and even the president himself, who stated that natural gas can provide 'safe, cheap power' and will 'help reduce our carbon emissions.'"

"That’s because scientists, engineers, state regulators and federal officials have concluded many times that hydraulic fracturing is a fundamentally safe technology that’s been used safely for more than 60 years," she added.

Both Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell and her predecessor, Ken Salazar have stressed the safety of the process "for decades."

Researchers at Stanford addressed concerns about natural gas or the fluids used in the fracking process leaking into drinking water supplies, concluding the risks of contamination are mitigated by the difference in depth at which fracking occurs compared to water sources.

While aquifers and other drinking supplies are usually no more than a few hundred feet below ground, fracking injections typically take place at 6,000 to 7,000 feet down.

"This said, there are instances where natural gas has been found in drinking water supplies, which is one of the problems that can be caused by poor well construction," explained Stanford geophysicist Mark Zoback. "If the steel well casing is not fully cemented, gas can leak up around the outside of the casing and contaminate shallow aquifers."

Zoback said the problematic wells typically "can be traced to leaking casings of very old wells that predate recent drilling for natural gas by 40 or 50 years."

The EPA, too, has toed the administration line, recently backing off a multibillion-dollar investigation into a Wyoming natural gas field in a move industry advocates cheered as a long-overdo correction to flawed science.

The study instead will be conducted by the state, and funded by EnCana, the drilling company at the heart of the alleged Pavillion, Wyo., aquifer contamination.

Critics say the Environmental Protection Agency appear to be "stepping off the gas," so to speak, for reasons they say are politically motivated.

Environmentalists point to a closed investigation into a groundwater pollution in Dimock, Pa.; a claim against a Parker County, Texas driller charged with methane gas bubbling into residents' faucets; significantly revised a 2010 estimate of the contribution leaking gas to climate change; and failing to enforce a ban on using diesel in fracking.

“We’re seeing a pattern that is of great concern,” said Amy Mall, a senior policy analyst for the Natural Resources Defense Council in Washington. “They need to make sure that scientific investigations are thorough enough to ensure that the public is getting a full scientific explanation.”

Oil and energy industry pressure on lawmakers -- and lawmakers bending to that pressure -- is hardly new in Washington.

And regardless of the science, there's one thing everyone seems to agree on: a broad dislike of the EPA.

"The EPA has put a 'kick me' sign on it," said John Hanger, a Democratic candidate for governor in Pennsylvania, one of the states where the fracking debate has been the hottest. "Its critics from all quarters will now oblige."