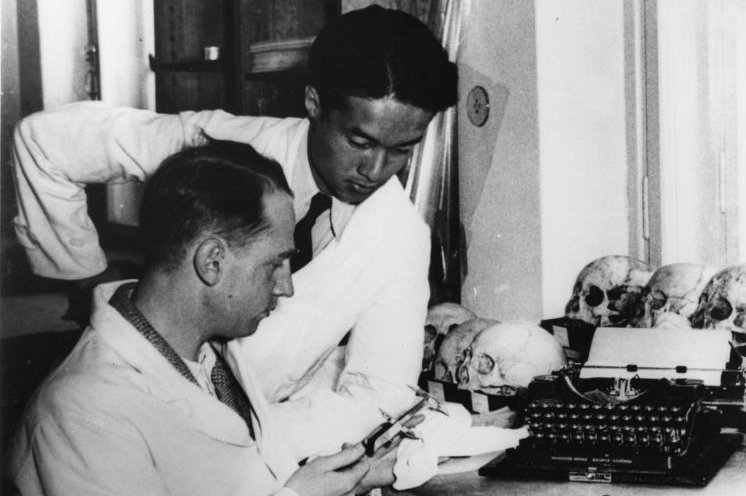

1 of 2 | Kim Paek-pyong, a Korean eugenicist at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics in Berlin, is seen standing in this undated photograph with an unidentified German associate measuring plaster casts of human hands. Photo courtesy of Frank Hoffmann/Archives of the Max Planck Society, Berlin

NEW YORK, Jan. 8 (UPI) -- Koreans who lived in Berlin during the period of Nazi rule briefly thrived under Adolf Hitler, despite the catastrophic ambitions of the Third Reich, according to a U.S.-based Korean studies specialist.

Frank Hoffmann, author of Berlin Koreans and Pictured Koreans, has studied the history of Koreans in the German capital from 1909 to 1940. He is also working on a book on the activities of the Manchukuo Embassy in Berlin, the outpost of the Japanese puppet state created during Tokyo's occupation of Manchuria.

Limited Korean espionage connected to the embassy and the hidden lives of the Koreans who lived in Berlin between the first and second world wars reveal relatively unexplored truths about Koreans of the Japanese colonial period, according to Hoffmann.

The group's ideological disagreements and the dissolution of their longstanding friendships may have even foreshadowed the political disputes and eventual division of the Korean Peninsula during the Cold War.

"In the '20s, you see the different political groupings," Hoffmann told UPI, referring to the group's leanings that ranged from socialist to royalist. Some Koreans at the time were advocating for the return of the Korean monarchy.

"But they still all work together. They talk to each other, they go to each others' weddings," he said.

That cohesiveness changed after 1945, according to Hoffmann. Koreans in Berlin returned to the peninsula, with some people repatriating to the North, others to the South, ahead of the armed conflict between the two sides.

Despite their differences, the Koreans in Germany appeared to be in agreement on one important issue by 1933, when Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany, and Japan had annexed Manchuria.

Any movement toward overthrowing Japanese rule was "completely dead" by then, Hoffmann said.

"Before, they would try to get something in the German newspapers" about Korean resistance movements, the analyst said.

Koreans in the Third Reich

Highly educated Koreans from wealthy families who collaborated with Japanese colonial authorities may have fared best under the Nazis.

Kim Paek-pyong, one of the Berlin Koreans, flourished in Germany while pursuing a career in medicine in the Third Reich.

Kim, a recipient of two German doctoral degrees and the author of a thesis on "racial differences in embryonic pig skulls," had a powerful mentor in Eugen Fischer, a Nazi eugenicist who had drawn the admiration of Hitler with his work on "bastards" and miscegenation in colonial German Southwest Africa, according to Hoffmann.

Despite possible involvement in eugenic sterilization projects in Germany, Kim was granted a special work permit in the United States after the war. Hoffmann was able to trace him to Belchertown State Hospital in Belchertown, Mass., where he was working in 1960. In 2009, Kim's remains were transported to the Korean National Cemetery in the South with "five other Korean-American patriots," Hoffmann's findings show.

Other Koreans who stayed on in the Third Reich may have helped with the Nazis' food supply. An Pong-gun, the cousin of revered Korean martyr An Jung-geun, could have worked as a soybean expert when the Germans were desperately seeking meat substitutes in wartime, according to Hoffmann's research.

Anand Toprani, an associate professor at the U.S. Naval War College, and author of Oil and the Great Powers: Britain and Germany, 1914 to 1945, said Germany at the time was short of every vital commodity for a major wartime economy.

"When it came to food, the Germans were happy to starve people, especially in the Soviet Union," Toprani said by email.

Some of the scarcities were addressed through the alliance with Japan, which supplied commodities like rubber, quinine, wolfram and tungsten not easily found in Europe, Toprani said.

The complicated histories and motives of the Berlin Koreans do not fit tidily into South Korean narratives about the colonial past.

Under President Moon Jae-in, Seoul pushed for the recognition of the Korean Provisional Government in Shanghai, founded in 1919, as the official starting point of modern Korea -- a controversial proposal that took many South Koreans by surprise. The Korean activists in the Chinese city may have represented only one of many "parallel" movements at the time, however, Hoffmann said.

Moon, who said in a speech delivered in Berlin in 2017 that Germany's experience with unification gave him hope regarding Korea's prospects, has praised the "peace and cooperation" that was integral to the process.

Eric Ballbach, a research fellow at Free University of Berlin, told UPI by email that economic conditions have improved in Germany since unification, but "mistakes" made are still felt today.

Complex identity questions remain, particularly among former East Germans who underwent a perceived loss of recognition and a general devaluation of one's own life by the West. Examples include people who worked in jobs specific to East Germany, such as news shows that were dismissed as "political propaganda" programs in the West, Ballbach said.

"The societal effects are obvious: While the discontented [Easterners] had turned away from politics and refused to vote in elections, the emergence of the right-wing populist party Alternative für Deutschland provided an opportunity to express their disappointment," the analyst said, referring to the surge of anti-immigration sentiment in 2019.

"While I think that reunification is an ongoing process, [it] is nowhere near completion."