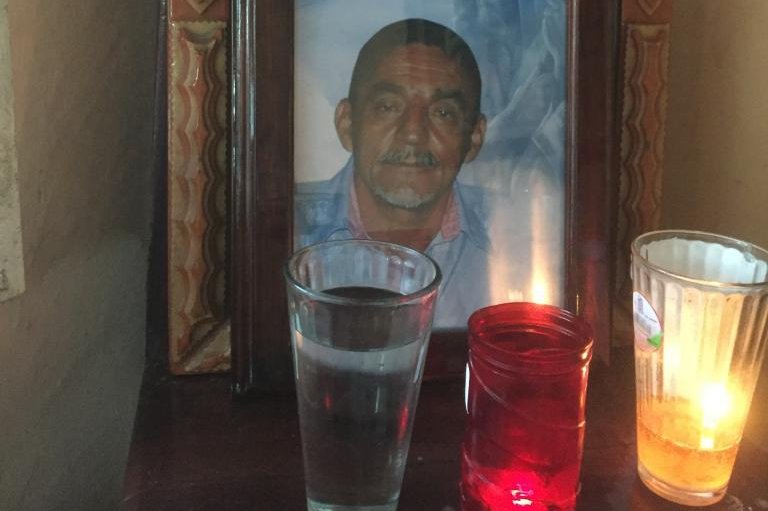

1 of 3 | A candle burns at a shrine to slain Mexican journalist Cándido Ríos in Veracruz, Mexico. Rios died in August 2017 after he was attacked by gunmen in a truck in one of the country's most dangerous areas for reporters. Photo by Patrick Timmons/UPI

MEXICO CITY, Sept. 4 (UPI) -- One year ago, Cándido Ríos became the first Mexican journalist enrolled in a federal protection program to be killed. Today, the case is unsolved, leaving his family and editor wondering if it was even investigated.

Meanwhile, a second journalist covered by the Mechanism to Protect Human Rights Defenders and Journalists, run by Mexico's Interior Ministry, was killed in late July and another reporter was killed this week.

Officials have said Ríos was not the target of the Aug. 22, 2017, attack that killed him and two others -- one a former police officer with ties to organized crime.

"Everything seems to indicate Ríos was in the wrong place at the wrong time," Roberto Campa, then-deputy minister for human rights in Mexico's Interior Ministry, said after the crime.

Ríos' family is not buying that explanation.

"The investigation into my father's murder stalled almost as soon as it began," daughter Cristina Ríos told UPI. "My father supposedly had federal protective measures since 2013. But these did not protect him. That's why Campa dismissed my father's work as a journalist as a motive for his murder."

The Mechanism provided Ríos with security cameras, reinforced locks and a panic button -- which were of little comfort to Rios' family, as he worked in an isolated part of southern Veracruz, the most dangerous region of the most dangerous state in Mexico. Since 2011, five other journalists from southern Veracruz have been killed, and one disappeared.

Jan Jarab, the representative of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights in Mexico, called on the government this week to ensure adequate funding to protect the 959 journalists and human rights defenders enrolled in the program.

"We must not forget the importance of the Mechanism," Jarab said in a statement. "Its existence has saved the lives of journalists and human rights defenders who are fundamental to the rights we all enjoy in Mexico."

But now with the slaying of Javier Rodríguez Valladares in Cancún on Aug. 29 -- the ninth journalist killed in Mexico this year -- advocates for endangered reporters say the government isn't doing enough.

The Ríos investigation

Mexican authorities entered Ríos in the protection program when the town's mayor, Gaspar Gómez, threatened him for reporting on corruption. In 2015, Rios urged readers of his newspaper, La Voz de Hueyapan, not to vote for Gómez. Two weeks before his death, he posted a video to YouTube in which he again criticized Gómez. By then, Gomez was no longer mayor, but he posted his own video and threatened to kill Ríos.

Ríos died in the small town of Juan Díaz Covarrubias. A year later, no one has been arrested.

"The investigative file does not point to any suspects and neither do investigators suggest a motive for Cándido's murder," said Jorge Morales, executive secretary of the Veracruz state Commission to Assist and Protect Journalists (CEAPP).

The Veracruz state prosecutor shares investigative files about journalist deaths with CEAPP, an autonomous body established by the Veracruz congress to confront violence against the state's journalists.

Morales said investigators looked into the dispute between Ríos and Gomez and even interviewed the former mayor, but did not draw any conclusions.

"I'm not surprised there have been no advances in Candido's case," Morales said. "This is the pattern in virtually every case of a murdered journalist in Veracruz. There are no breakthroughs, just impunity. We aren't seeing any results out of the prosecutor's office."

Jaime Cisneros, Veracruz's special prosecutor for crimes against journalists, declined to provide any information to UPI about the Rios investigation, citing confidentiality requirements.

Cristina Ríos said, "Nobody has been in touch with us about the investigation. Nobody has told us who killed my father. There is nobody in prison for his murder. The support public officials promised my mother has never materialized."

"We don't know anything more about who murdered Cándido or why. Nobody has told us anything," Cecilio Pineda, editor of El Diario de Acayucan, where Ríos worked for a decade, told UPI.

"I've done some investigating for myself. I think perhaps he might have been in the wrong place at the wrong time. But the thing is, the authorities haven't investigated the other two men murdered either. This really shows the extent of the impunity," Pineda said in a telephone interview from Acayucan, Mexico.

"None of this I find surprising," he added. "What would really have surprised me is if they had investigated the case and said, 'yes, he was in the wrong place at the wrong time' for this reason or that reason or another reason. But the authorities did not even do that."

None of the cases of the 12 journalists killed last year have been resolved through prosecution.

Ríos' dedication

The day of his death, Ríos repeated his daily routine: rising at dawn and eating breakfast with his wife of many years, Hilda Nieves. He fed the pigs the couple were fattening in their front yard so Hilda could make longaniza, spicy pork sausage, to sell in town. Ríos, who did not have a car, would then set off to walk through the hot, humid town, noting events to report and selling the newspaper he wrote for.

For many years, El Diario paid Ríos with the proceeds of the newspapers he sold in the town. His daughter said he wandered the neighborhoods informing people about what was happening in Veracruz, Mexico and the world.

"He had this brave commitment to informing people in his community," Cristina Rios said. "He used to publish his own newspaper, La Voz de Hueyapan, but people broke into the house and stole his photocopier and printer. But even that didn't stop him. He used to go to an Internet cafe in town to print his paper. My father was my hero because he helped keep people informed."

Organized crime dominates southern Veracruz, prized for its strategic location on Mexico's Gulf Coast and highways linking it to Mexico City. Southern Veracruz is rife with fuel thieves, human traffickers and drug smugglers. State and municipal police and public officials often work hand in glove with organized crime. A few years ago, the Zetas dominated, their place now taken by the Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación -- making reporting on corruption and crime a difficult, dangerous task for rural journalists trapped between politicians, state security forces and organized criminals.

In spite of the danger, threats and the slaying of colleagues, Ríos continued reporting. After his workday, he would often stop for a soda at the convenience store on the main road. He did exactly that on the day he was killed.

At the store, he spoke with two acquaintances in the parking lot, one a former municipal police officer. Within a few minutes, all three lay dead, killed by gunmen in a speeding truck.

When the family later recovered Ríos body from the morgue, his personal belongings, including his writing case, were missing. They have not been recovered.

Hilda Nieves only remembered it was their wedding anniversary later that evening.

Funding for protection

Jan-Albert Hootsen, Mexico's representative of the Committee to Protect Journalists, said the Mechanism established in 2012 to protect reporters and human rights defenders has proven "woefully insufficient."

"Mexico is one of only a few countries in the world where the trend of deadly violence against reporters has increased," he said. "In the rest of the world, attacks on journalists have decreased. This means preventing attacks on journalists in Mexico has been insufficient and the federal mechanism should provide a vital role in that prevention."

But that alone isn't enough, he said.

"It will be unable to perform its tasks if it is the only player around. If all the other institutions in Mexico don't show a real interest in dealing with impunity and dealing with violence, then the Mechanism will have enormous difficulties fulfilling its most basic functions.

"It's a relatively small institution with a relatively small budget supported by a public trust fund. It's offices are centered in Mexico City and it doesn't have regional representation. Evaluation of risks is very difficult for the Mechanism."

Mexicans suffer the worst impunity rating for crime in Latin America, followed by Peru, Venezuela, Brazil and Colombia, according to the Global Impunity Index, an annual survey of authorities' responses to crime.

Cristina Ríos said she is resigned to her father's case languishing, unresolved.

"I should imagine our situation is similar to that of other crime victims in Mexico and Veracruz," she said. "It's very sad. Living without my father has been very difficult for my family, and especially for my mother."