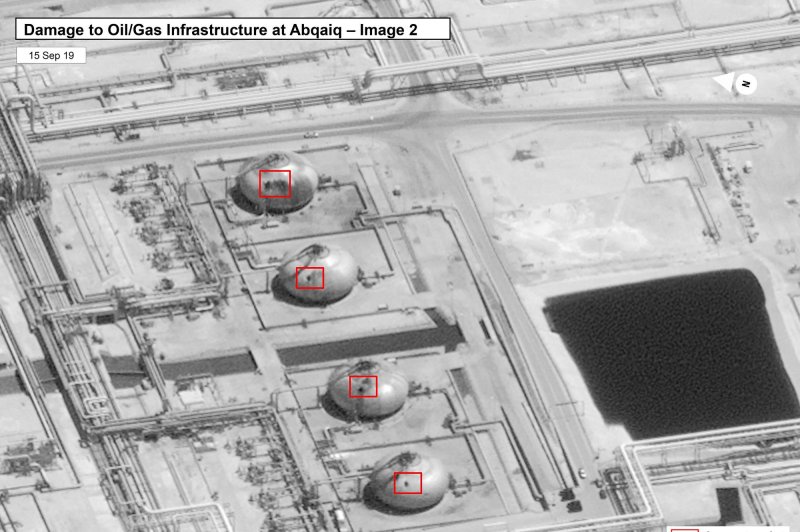

The damage caused by a drone attack on Saudi Aramco's Abaqaiq oil processing facility in Buqyaq, Saudi Arabia, can be seen in this image released by the U.S. government and DigitalGlobe on September 15. Photo via U.S. government/Digital Globe |

License Photo

Make no mistake: The recent attacks against Saudi oil facilities were impressive by any standard. While countries with advanced weapons could have imposed as much damage, attacking without absolute attribution is a far more difficult and higher bar of operational prowess. But regardless of attribution, these strikes are especially worrying, well beyond whether retaliation against Iran follows by Saudi Arabia, the United States and other parties.

So far, the Trump administration has been cautious in ruling out war with Iran. That could change. The current lack of bellicose rhetoric from the White House could prove to be disinformation to mislead Iran. But until proof of blame moves beyond the inferential to what analysis and forensics can demonstrate well beyond any doubt Iranian complicity, the administration should be commended for its approach.

Yet, several takeaways are frightening. First, despite the many hundreds of billions spent on defense by the United States and Saudis on detection and surveillance systems, if unimpeachable attribution cannot be established, outliers will seize on this vulnerability to be exploited by the second factor. Armed with a cellphone, "WhatsApp" or other program and a 3D printer that can easily turn out modern drones, the possible scenarios bring a new face to old war. These and other technologies can disrupt and destroy critical national infrastructure possibly without attribution and at very low cost.

Historically, this form of warfare allowed militarily weaker forces to prevail over far stronger ones. Wellington's Peninsula campaign in Spain in the early 1800s bled Napoleon. A hundred or so years later, Lawrence did the same to the Turks in Arabia. These asymmetries applied in the Philippines, Algeria, and of course in Vietnam. Armed with Stinger and other missiles as well as suicidal resistance, the mujahedin forced the superpower Soviet military out of Afghanistan. Today, the Taliban have not been vanquished by American military might despite lacking a modern army and air force.

Because of technologies that no longer are the exclusive domain of states, consider certain scenarios that should not be considered as "unthinkable." Suppose 50 or 100 drones were launched against the electrical grid of any nation. Or mine-laden underwater autonomous vehicles were covertly planted in channels to and from major seaports. The impact from the damage could eclipse what happened to the Saudi oil fields.

In 1980, the Center for Strategic and International Studies released a report arguing that America's greatest single vulnerability was its electrical power grid. That vulnerability has grown considerably worse. Indeed, in some cases, replacing damaged or destroyed transformers essential to electrical distribution could take a year or more given production schedules.

While fear of so-called "cyber Pearl Harbors" is perhaps exaggerated, physical destruction of critical infrastructure with current and readily available technologies is not. The Saudi case is exhibit A. This leads to three crucial and possibly unanswerable questions.

First, if absolute attribution of the attackers who managed to cut for a time about half of Saudi oil production cannot be established, what can be done to prevent future incidents? Second if attribution can be proven, what follows? But third and perhaps most importantly, how can the vulnerability of vital infrastructure to readily available and destructive technologies be reconciled?

The U.S. National Defense Strategy is based on great power competition with Russia and China. Further and clarifying the Obama so-called four-plus-one strategy against potential threats, the NDS called for "deterring and if war comes defeating" a range of possible adversaries, beginning with China and Russia. But suppose the greater or more likely threat is posed by the same technologies that temporarily demolished Saudi oil facilities. What is the strategy for these scenarios?

Indeed, are the current and highly capable and expensive defenses required in modern combat suitable for conditions arising from this newer face of older war? For the moment, this is the unaddressed quandary. And in fairness, we may be at the very beginning of this danger materializing.

After two nuclear weapons leveled Hiroshima and Nagasaki ending World War II, it was not until the development of thermonuclear weapons posing potentially existential dangers to states that deterrence became the aim. Cellphones, 3D printers and drones have not yet come to the point where their destructive power even remotely approaches thermonuclear weapons. But that does not mean these technological combinations could not threaten imposing grave levels of societal damage and disruption.

Whether we have time to think this new challenge through or not, we better start now.

Harlan Ullman is UPI's Arnaud de Borchgrave Distinguished Columnist and a senior adviser at the Atlantic Council. His latest book is "Anatomy of Failure: Why America Has Lost Every War It Starts." Follow him @harlankullman.