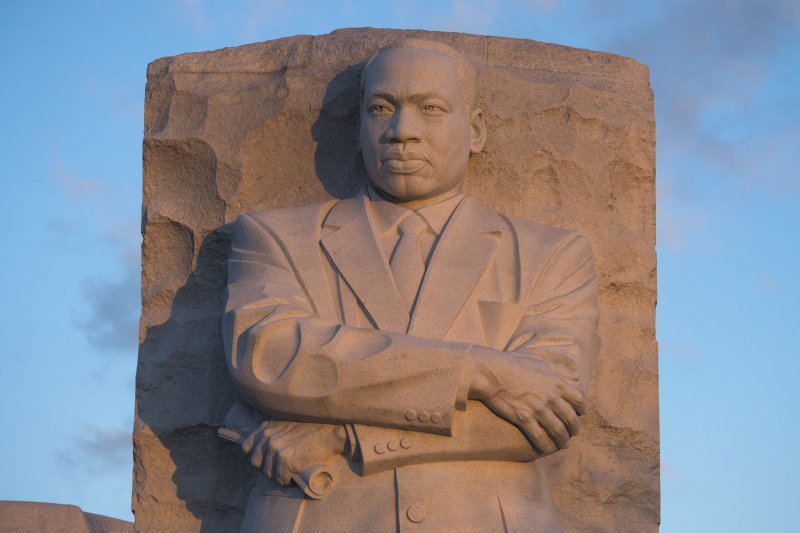

1 of 2 | The sun rises on the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial on Martin Luther King Jr. Day in Washington, D.C., on January 21. File Photo by Kevin Dietsch/UPI |

License Photo

Aug. 28 (UPI) -- It was Aug. 28, 1963, a hot Wednesday afternoon in Washington, D.C., Martin Luther King, Jr. seized the American imagination with his dream for this nation. He spoke of his vision of a time when little black boys and black girls would be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.

Aug. 28 also happens to be the day on which, eight years earlier, one mother's dream for her child came to a tragic end. In the predawn hours of Aug. 28, 1955, Mamie Till's 14-year-old son, Emmett Louis Till, was dragged from a relative's home in Mississippi and "lynched" after being accused of "flirting" with a 22-year-old white woman.

On this Aug. 28, decades after King's speech and Emmett's lynching, these two events still capture the searing truth of our nation. It is a truth rooted in our nation's founding.

When America's Pilgrim and Puritan forebears fled England in search of freedom, they believed themselves descendants of an ancient Anglo-Saxon people who possessed high moral values and an "instinctive love for freedom." They crossed the Atlantic to build a nation that was politically, culturally true to their "exceptional" Anglo-Saxon heritage. The America they envisioned would be a testament to the sacredness of Anglo-Saxon character and values.

The perpetually vexing problem for the actual nation they founded lies in the reality of its demographics. From its very beginnings, America has been an immigrant nation, including migrants -- even from Europe -- who were not Anglo-Saxon. For those who were white, however, whiteness became the passport into the exceptional space that was America, with the rights and privileges of citizenship. Whatever one's heritage or one's values, to be white was to be considered Anglo-Saxon enough.

With this, a culture of white supremacy was born. The myth of Anglo-Saxon, white superiority became inextricably linked to America's social-political and cultural identity.

W.E.B. Du Bois' classic 1903 book The Souls of Black Folk uses the metaphor of "warring souls" to describe the resulting existential dilemma of African Americans. Borrowing from his words, America is a nation with "two thoughts, two un-reconciled strivings, two warring ideas." The image of a warring soul aptly defines our nation and reflects the contradictions intrinsic to this nation's founding identity.

The architects of America's "democracy" shared the founders' Anglo-Saxonist vision. Thomas Jefferson believed unapologetically in white superiority and black inferiority. Though he expressed a conviction that slavery was contrary to America's ideals of freedom and democracy (while owning slaves himself), he maintained that the black enslaved were irrevocably inferior to white people. In an 1814 letter to his friend Edward Coles, an abolitionist, Jefferson referred to black people as "pests in society" and warned that their "amalgamation with the other color produces a degradation to which no lover of his country, no lover of excellence in the human character can innocently consent."

For his part, the "Great Emancipator," Abraham Lincoln, boldly declared, "There is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. And inasmuch as they cannot so live, while they do remain together there must be the position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race."

That those who conceived of America's democracy could at once harbor a vision for America where all were equal and yet hold deep white bias and bigotry reveals the complex truth of this nation. Baked into the very fabric of this country is a white supremacist narrative that taints its very democratic vision. The myth of Anglo-Saxon exceptionalism and white superiority runs deep within the DNA of this country despite its vision to be a nation of liberty and justice for all. The nation's soul is in constant war with itself.

The resurgence of deadly, bigoted violence in this country, recently seen in El Paso, Texas, and in Gilroy, Calif., should come as no surprise. It reflects the hard truth of this nation's origins and the ugly unresolved dilemma of its very soul. The notion of innate Anglo-Saxon white superiority can erupt with little provocation, especially when it comes from the highest offices of the land. These are simply 21st century manifestations of America's founding myth of Anglo-Saxon exceptionalism and the culture of white supremacy that protects it.

On this Aug. 28, let us not forget King's dream and Emmett's lynching. Even as we remember that 56 years ago King stood in front of the Lincoln Memorial calling for the nation to live beyond its biases into its highest aspirations, let us also remember that 64 years after Emmett's murder, the Mississippi memorial to him is continually desecrated with bullets.

We have yet to decide if we are going to be a nation and a people defined by King's dream or a nation and a people defined by Emmett's lynching. Our warring soul needs to be settled.

Kelly Brown Douglas, dean of the Episcopal Divinity School at Union Theological Seminary and the Canon Theologian at the Washington National Cathedral, is the author of "Stand Your Ground: Black Bodies and the Justice of God." The views expressed in this opinion piece do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.