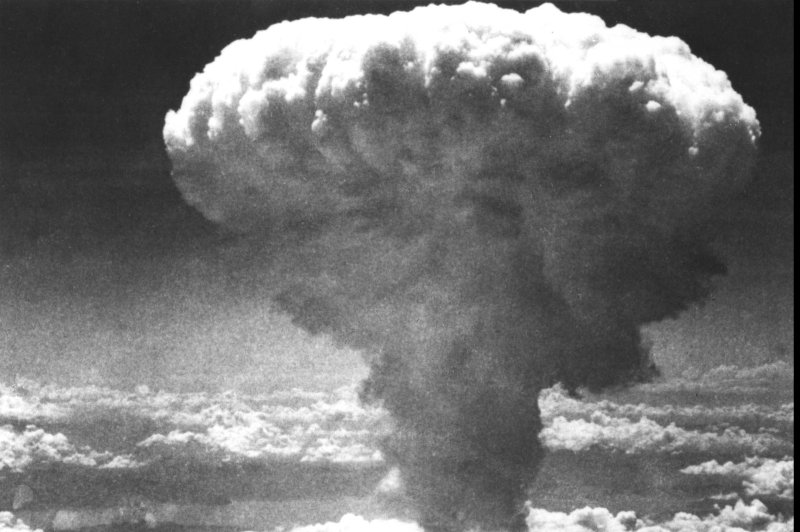

Nagasaki, Japan, under atomic bomb attack on August 9, 1945. Two planes of the 509th Composite Group, part of the 313th Wing of the 20th Air Force, participated in the mission. UPI Photo/USAF/File |

License Photo

Nov. 19 (UPI) -- Has Dr. Strangelove, that magnificent Cold War parody of the absurdity of nuclear war, been resurrected in the defense thinking of the major nuclear powers?

With the Trump administration's unilateral abandonment of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) that would have prevented Iran from gaining nuclear weapons if fully implemented, and the 1987 Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty that eliminated U.S. and Soviet land based missiles with ranges from 550-5000 kilometers, the specter of a nuclear arms race is real. Talk of "limited nuclear war," if such a holocaust could be kept limited, has returned as if this were the 1950s and 1960s.

Yet, the last two administrations have taken seriously the contingency of dealing with two near or peer competitors as the focus of defense planning. The strategic center of gravity of the current national defense strategy, to borrow from the great military philosopher Karl Von Clausewitz, is "to deter and if war comes defeat China, or Russia or Iran" -- and now less so North Korea with the Kim-Trump romance.

In fact, this "strategy" follows-on from the Obama "five plus one" construct that also was directed at deterring and, if necessary, defeating these states while countering violent extremism.

The just-released congressional Commission on National Defense Strategy report obliquely challenged this deter and defeat requirement, recommending that the Pentagon produce operational concepts for implementing this "strategy." Quotation marks are put in place because "deter and defeat" is by no means a strategy. Rather it is a goal or aspiration. If it were a real strategy, it would link ends and means with a plan including the necessary resources to achieve these outcomes along with a cost-benefit analysis of risks and gains. The National Defense Strategy does neither.

Hence, the questions that should have been addressed by both the Obama and Trump teams before stating this strategic aim are, what does it take to deter and defeat China or Russia and deter from what? These questions remained unanswered. As long as they do, the National Defense Strategy remains hollow and surely open to intense debate and dissent.

The Cold War was much easier. The East-West standoff was viewed very much in World War II terms of democracy versus a new version of fascism -- an ideological battle on which the future of peace and stability rested. Nuclear and thermonuclear weapons once developed profoundly altered the nature and character of war.

In a thermonuclear war, the notion of winners and losers that could be ascribed to earlier conflicts no longer applied. Society would almost be destroyed under thousands of mushroom-shaped clouds, and made unlivable by the radioactive properties of plutonium with a half life of tens of thousands of years.

To understand the power of these weapons, which few people today do, even a "small" nuclear explosion of 12 Kilotons, the size of the Hiroshima bomb, is equivalent to 12,000 tons of TNT. A megaton thermonuclear or boosted fission bomb is equivalent to 1 million tons of TNT. And that does not include the effects of radiation -- does anyone remember Chernobyl?

Further, how does the United States "deter" Russia from using its most effective weapon -- active measures that applies misinformation, disinformation, propaganda and intense meddling into the domestic politics of others. Or China from militarizing tiny islets off its coast or gaining access and influence through its "belt and road" campaign? The answer is that we do not have the answers to this question.

The defense strategy is absolutely correct in shifting focus from 17 years of countering violent extremism to the possibility of encountering adversaries with weapons and strategies equal to or superior to ours. However, are we not better off not naming precisely who those adversaries are, since there is no overarching reason why war with China, Russia or Iran is inevitable unless we are supremely stupid or arrogant?

The U.S. is fearful that Russia could invade and occupy the Balts as it did Crimea. But why would Russia risk that and for what gain? One could argue that such a scenario is as likely as NATO invading Kaliningrad, the tiny Russian enclave in the Baltic physically separated from Russia -- or about zero.

China might choose to invade Taiwan as it has frequently threatened. But the straits are wider than the English Channel, as Hitler found. And Taiwan is not undefended.

In a non-Strangelovian world, the simple solution would be serious talks among these three powers to ensure that war was impossible. That is the only way to deter because there will be no victors in a future global war that could be thermonuclear.

Dr. Harlan Ullman is UPI's Arnaud deBorchgrave Distinguished Columnist. His latest book is Anatomy of Failure: Why America Has Lost Every War It Starts. He can be reached on Twitter @harlankullman