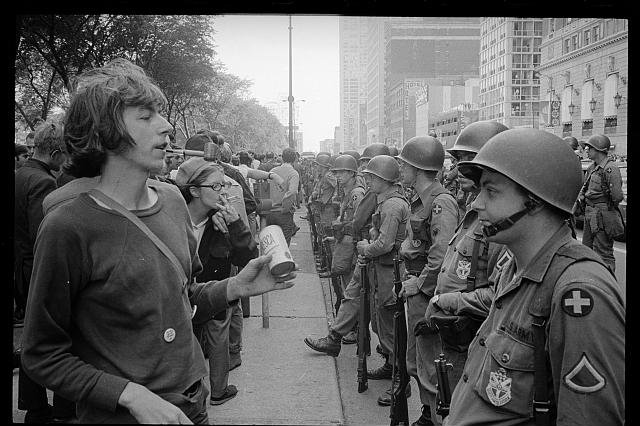

A young "hippie" stands before a row of National Guard soldiers across the street from the Hilton Hotel at Grant Park, at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago on August 26, 1968. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

It was a beautiful late-summer evening in Chicago -- except for the clouds of tear gas hanging over Grant Park, the wailing of sirens and the crowds of demonstrators chanting, "The whole world is watching" as they were being clubbed by police.

Oh, and blood gushing from a wound in the back of my scalp, courtesy of a police nightstick, that later required stitches in the Northwestern Memorial Hospital emergency room.

It's been 50 years since Aug. 28, 1968, the climax of a week of protests surrounding the Democratic National Convention. When the dust settled many months later, Hubert H. Humphrey, the candidate nominated during the chaos, was swamped by Richard Nixon in the general election and the official report on the convention street action called the events of late Aug. 28 a "police riot."

Fifty years is a long time and much has changed. But given the political climate of 2018, it's worth a look back half a century to recall what happened, why it happened and how the lessons we might have learned then are important today.

My story is the easy part of the narrative.

I began work at United Press International on Aug. 27, 1968, walking in the front door of 430 N. Michigan Ave. for the night shift with only college newspaper experience. The building, by the way, is the one Bob Newhart exited in the opening scenes of his 1970s television show. The Billy Goat Tavern was -- and still is -- on the lower level.

The next day, my second day on the job, night editor Everett R. Irwin dispatched me to cover a march by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference "mule train" that was credentialed by the city to roll down Michigan Avenue from the Chicago River to the Conrad Hilton Hotel, the headquarters hotel for the convention. Only call in, I was told, if something really important happens. I gathered the ignorant new staff member was being shooed out from underfoot.

The march was uneventful for exactly seven blocks.

At Jackson Drive, thousands of protesters had finally found a way past the police and national guard barricades that had kept them penned in the lakefront Grant Park most of the day, victims of repeated attacks with clubs and gas. The beleaguered crowd poured across a bridge over railroad tracks on the south side of the Chicago Art Institute just as the mule-drawn wagon arrived at the intersection of Jackson and Michigan.

Cheering and shouting, the crowd swamped the "legal" protest and marched south toward the Hilton, filling the street and sidewalks. The mule train quietly disappeared.

The forces of law and order were unprepared for the "end-around" march to one of the city's most sensitive spots and hastily drawn police lines finally stopped the march just south of Balbo Drive, which meant the chanting demonstrators were right in front of the hotel housing the biggest of bigwigs -- among them presidential candidate George McGovern, who watched the ensuing melee from his room. Soon more police, National Guard troops and assorted law enforcement vehicles sealed off the intersection from all four directions.

Violence breaks out

As night fell, the police had their fill -- and then some -- of the demonstrators. Whether under orders or not, they charged into the crowd, running down some people with three-wheeled motorcycles, clubbing and kicking others. Part of the crowd was pushed against the plate glass window of the Hilton and, when it broke under the pressure, fell into the building in a shower of glass.

I was on the south edge of the crowd, pushed back against the police line on Michigan Avenue. When I heard the thwacks of the clubs and the screaming of the crowd, I foolishly turned to the north to look at the action. That presented my back to the police and I was immediately struck on the back of the head and knocked to the pavement.

By the time I got up, the police line had moved past me and many of the blue-helmeted squad were enthusiastically clubbing people -- both those trying to escape and those already on the ground.

Even before the violence ended, the crowd was chanting what became the catchphrase for the street-action part of the 1968 Democratic National Convention -- "The whole world is watching! The whole world is watching!"

In fact, the whole world wasn't exactly watching live. Television technology had not advanced quite that far by 1968. But within minutes, tape of the altercation was being shown on all the networks and, eventually, seen in a good part of the world.

There was no way to negotiate the 1.2 miles back to the UPI bureau other than to walk. Dusk gave way to darkness as I trudged back up Michigan Avenue, blood seeping from the scalp wound to basically saturate my sports jacket. I rode the elevator up to the fifth floor, walked past the National Broadcast desks and sat down in a chair next to Sue Taylor, who was frantically filing the Illinois radio wire and emitted a shriek when she noticed the bloodied stranger.

A photographer drove me to the hospital in the company of another reporter, who quizzed me on what had happened and later wrote and filed a first-person story under my byline -- my first A-wire byline on my second day on the job. And not a bad story.

Five stitches and some bandaging later, I was told not to come back to work until I felt better. That was nice. It also was a career boost that the entire editorial hierarchy of UPI, both in Chicago and in the New York world headquarters, now knew my name.

And, of course, any misstep in the future would bring the reasoned excuse, "Hey. You can't blame me. I got hit in the head."

The rest of the story is a lot more complex.

Chicago unprepared

First, how did this ever happen?

In today's world, most cities are more than capable of handling most protests with a minimum of fuss, certainly minimizing outright violence involving the police. That wasn't the case in 1968. And it most certainly was not the case in Mayor Richard J. Daley's Chicago.

Daley was elected mayor in 1955 and by 1968 had consolidated power within government and the local Democratic Party to the extent that his word was law. He was an old-school guy who believed in order, respect and civility. He was deeply proud of his city and eager to show it off as the site of the convention.

The mayor was totally unprepared, to the core of his being, for what descended on Chicago. By 1968, the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act had been passed and much of the white activist ardor had been refocused from civil rights in the American South to the war in Vietnam. Marches, sit-ins and boycotts had proved effective and more of the same was the order of the day.

There was another aspect to the Vietnam protests, though -- the military draft. Young people were at actual risk of being plucked from their safe and comfortable lives and sent to the jungles of Southeast Asia. Altruism was heavily spiced with a very real, personal fear.

With Lyndon Johnson not seeking re-election and Sen. Robert Kennedy dead of an assassin's bullet, Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey was the front-runner for the nomination. And, forced to defend "Johnson's war," he was not popular with the anti-war movement. And so they came to Chicago.

And Daley disastrously decreed that, no, they would not be allowed to sleep in the parks.

Many had planned to do just that. Daley's decision prompted night after night of sometimes violent, always abrasive, contact between protesters and police who were ordered the clear the parks. Tempers quickly became frayed on both sides as police dodged missiles and endured nasty name-calling while dishing out punishment and tear gas.

And then came Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin -- charismatic rabble-rousers who knew exactly how to whip up the crowds and get under Daley's skin. The "Yippies" variously announced outrageous plans. One day they were going to put LSD into Chicago's water supply. Another, they were going to compromise convention delegates with "hippie hookers". Another time, they held a mock convention on Daley Plaza to "nominate" a pig as the Democratic candidate.

"What are we coming to as a society?" Daley asked a television interviewer. "What are we coming to as a country if policemen are treated the way they have been treated -- not only in Chicago but all over the country?"

Daley would not allow his city to be mocked. The police followed his lead and his orders and the confrontations grew. By Aug. 28, he had fallen completely into the snare set by Hoffman, Rubin and co. The police rank-and-file were outraged and angry. So were the demonstrators. Something had to give. It gave in front of the Hilton.

Lasting impact

The impact of the street battle was both immediate and long-lasting.

On the convention floor, Sen. Abraham Ribicoff, D-N.Y., departed from his nomination speech for McGovern to condemn "Gestapo tactics" by police on the city's streets, noting the violence was "competing with this great convention for the attention of the American people."

Daley, seated directly in front of the podium, snarled a response that was not picked up by microphones but, according to lip-readers, vulgarly impugned Ribicoff's religion and ethnicity. McGovern himself, after watching from his room at the Hilton, also quickly condemned the police action.

Humphrey came out of the convention trailing Nixon badly in the polls, saddled with his close connection to Johnson and with George Wallace siphoning off support in the formerly Democratic South. Through a combination of strategies and circumstances, he rallied in the final month of the campaign to make the final result close. Did the impact of the convention chaos put him too far behind?

Months after the convention, a report titled "Rights In Conflict," compiled under the direction of corporate attorney Daniel J. Walker, found the action in front of the Hilton was a "police riot".

"The nature of the response (to the demonstrations) was unrestrained and indiscriminate police violence on many occasions, particularly at night," the report said. "That violence was made all the more shocking by the fact that it was often inflicted upon persons who had broken no law, disobeyed no order, made no threat. These included peaceful demonstrators, onlookers, and large numbers of residents who were simply passing through, or happened to live in, the areas where confrontations were occurring."

Walker later became governor of Illinois and, still later, went to prison for offenses unrelated to his government service.

Hoffman, Rubin and six others were indicted on charges of conspiring to cross state lines to incite riots. Black Panther leader Bobby Seale, one of the original "Chicago Eight", was removed from the case but the others, after a trial that often devolved to sideshow dimensions, were convicted. The convictions were overturned by an appeals court highly critical of Judge Julius J. Hoffman (no relation).

Daley died suddenly Dec. 20, 1976, plunging Chicago into years of political turmoil. His son, Richard M. Daley, was elected mayor in 1989 and served until 2011.

Fifty years on, none of the police officers who served at the time of the convention is still on the job.

Many of the protesters who took to the streets of Chicago, however, remain active in the 2018 political scene. I remain active, proudly writing for UPI.