March 23 (UPI) -- Latin American democracy was born with an original sin: income inequality – the highest in the world. Thus it was that the region's democratic institutions originated in a context of severe social exclusion and poverty.

The U.S.-style Madisonian model of democracy implemented across the region as its prevailing dictatorships ended in the 1980s – characterized by general elections, separation of powers, built-in checks and balances and civil control of the armed forces – did not match most Latin American nations' cultural identities.

That disconnect left significant gaps in governments' ability to connect with and serve their people. Though democracy in Latin America is young, these fundamental structural problems have remained unsolved for 30 years, and they partially explain the region's numerous current socio-political crises, from Brazil and Venezuela to Mexico.

In response, Latin American presidents are inventing new ways to exercise leadership – namely, via social media. By 2014, the region had the world's highest use of social media use by politicians.

Fill the vacuum (and the airwaves)

In the crowded Twittersphere, the presidents of Venezuela and Ecuador are standouts – both for their large followings and continuous activity.

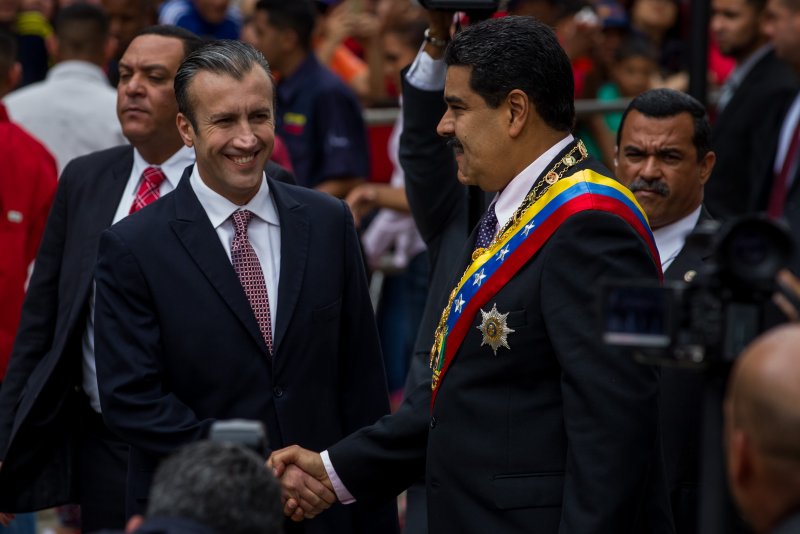

Venezuela's Nicolás Maduro, for instance, has over 3 million followers. His account exhibits his entire presidential platform, daily commitments and "personal" relationships with constituents, from messages railing against the Organization of American States to the unveiling of public works.

Ecuador's Rafael Correa, who in 2014 was the third-most prolific politician on Twitter (after the leaders of Uganda and Rwanda), has a similarly broad audience. Currently, his account is full of opinions on the country's current presidential election. But an episode of the podcast Radio Ambulante recounts how Correa once trolled an Ecuadorian citizen on Twitter after he posted a critical Facebook comment.

Both Maduro and Correa frequently appear on television reading the tweets they've received, mentioning by name – for better or for worse – those who've sent them messages. The citizen, who is now also the spectator, in turn feels he has been served, made part of the political game, become visible.

Twitter is not only the purview of the political left. Conservative former Colombian President Alvaro Uribe used social media while in office, as does the country's current president, Juan Manuel Santos.

Argentina's Mauricio Macri is a Snapchat fan; it forms part of his official communications strategy).

A governance crisis

Politics is not just about running the government, it's also about creating opportunities for citizens to realize their aspirations. Because Latin American democracy was, in most cases, rolled out without a robust consultative process, decent education system or a plan to address structural poverty, it's systematically exclusionary.

The silenced voices of the rural poor, indigenous communities, women and those unable to read, were not heard or considered when creating and implementing public policies. As a result, governments today struggle to respond to the demands of many social sectors.

There are two ways to fill this gap. The first is suppression via the use of force. Though this is fairly common in Latin America, as an official policy it undermines state legitimacy.

The other option is to create new mechanisms for state-society relations. Latin American leaders, then, are using social media to engage with the electorate because their democratic institutions – fragile and insufficient – are not able to effectively receive, process and address citizen demands.

This direct communication redefines the governor-governed relationship, creating an imagined social interaction in which the political leader is "bound" to his subject by virtue of recognizing a tweet. With Twitter, the ordinary person may believe that she has sent a message directly to a person in power, informing them of something they did not know. She may feel less anonymous, more emboldened and capable of navigating the complexities of government bureaucracy.

But Twitter engagement is not (re)constructing republic-style citizenship in Latin America. Rather, it is building an artificial relationship derived from the notion that power dynamics between citizens and politicians have been eliminated.

Direct digital interlocution with a president creates what Polish sociologist and philosopher Zygmunt Bauman would call a false sense of community.

This process also implies clientelism, turning presidents into patrons and citizens into clients. Most Tweets and Facebook messages to Latin American leaders are petitions or requests – people asking the all-powerful leader to fix problems with public services or provide financial assistance.

Perverse mechanisms, broken system

The problem is that the way this works undermines the legitimate mechanisms of government. Making the masses dependent on digital communication with a specific leader leaves existing institutional dynamics and control mechanisms entirely out of the process.

When a crime is reported to the president, what role have the courts? When the president learns that a sewer is leaking, who tells the municipal government? The Internet enables dialogue and personalizes discourse, but it does not in itself have the capacity to resolve people's problems.

Social media as a political mechanism also carries other risks for governance. The excess of information transiting on social media and the difficulty of verifying its validity can distort public opinion and, according to research, negatively affect the ability of decision-makers to assess challenges.

We must also consider that decision makers (like many of us) tend to hear what they want to and ignore the rest. So beyond their administration's principle concerns, leaders may be interested in how many people follow them, but not necessarily in fixing what ails their followers.

Hence, Maduro can seemingly overlook the fact that thousands of Venezuelans are fleeing the country. At the end of the day, his virtual audience remains intact and his TV show still beams out to millions of viewers every Sunday.

Latin America's #Twitterpoliticking trend might be an entertaining curiosity if it didn't so clearly reveal the fundamental weakness of the region's democracies. This failing stems from political systems founded on inequality, social exclusion, illiteracy and elitism. And it's not something social media can fix.

Miguel Angel Latouche is an associate professor at the Universidad Central de Venezuela. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.