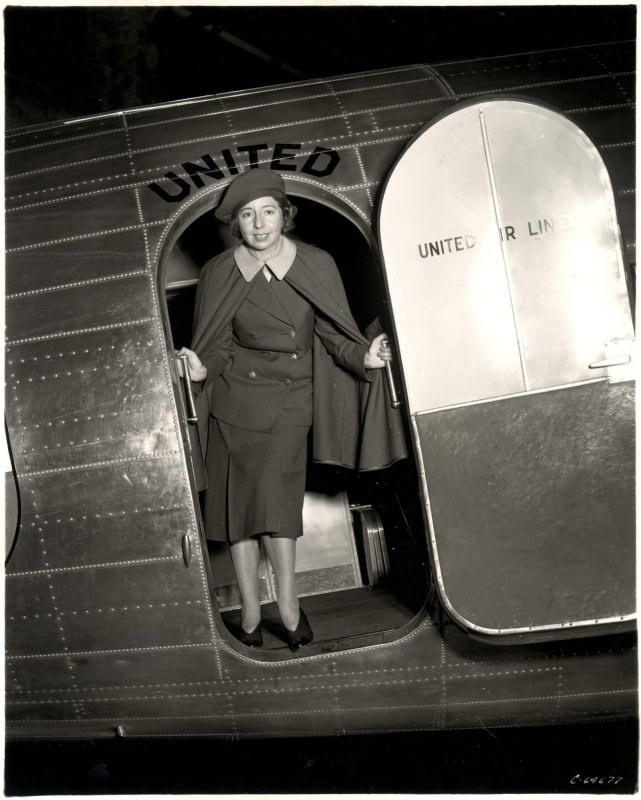

1 of 4 | Ellen Church poses standing in doorway of United Airlines Douglas DC-3 wearing an original stewardess uniform, circa 1930. File Photo courtesy of Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum

May 15 (UPI) -- As flight attendants learn to navigate new working conditions -- and potential job losses -- amid the coronavirus pandemic, Friday marks the anniversary of the flight that in many ways gave birth to the job as we know it today.

Ninety years ago on May 15, 1930, Ellen Church led the first group of what were then called "stewardesses" on a Boeing Air Transport -- now United Airlines -- flight. Church and three other young women served as flight attendants on the trek from San Francisco to Chicago, which took 20 hours and 13 stops for 14 passengers.

Four fresh flight attendants took over the flight during its leg from Cheyenne, Wyo., to Chicago.

Church wasn't just an ordinary flight attendant, though. Her desire to put her expertise and background as a pilot and nurse to use in the skies is part of what led to women taking over the flight attendant role.

Before she and the seven other inaugural flight attendants came into the picture, only men served the friendly skies -- both as pilots and in some cases, stewards. Sometimes pilots performed dual roles, flying the plane and handing out coffee and sandwiches.

Church initially wanted to be a pilot on commercial flights, but at the time, airlines only allowed men behind the yoke. Instead, she suggested women -- specifically nurses -- take over the role of flight attendants. She told BAT that nurses could better help new fliers through airsickness and be useful during any medical emergencies.

Having women in the role could also help put businessmen's fears of flying at ease -- perhaps 1930s-era men would put on a better show of bravery if a handful of fearless women hauled their luggage and served them coffee.

Church's argument was bolstered by a simultaneous suggestion by BAT official Steve Stimpson after a particularly rough flight. The turbulence meant the pilots were too busy to serve refreshments during the flight, so Stimpson took over the job of handing out drinks and sandwiches.

When he got back to the office, he told BAT management it needed to hire dedicated stewards.

Top brass took both ideas and began a trial program to have women serve as stewardesses. Church was tasked with training the new attendants and eventually wrote a manual on the position.

At the time, she was to ensure that all flight attendants weighed no more than 115 pounds and be no taller than 5 feet 4 inches. They also had to be registered nurses.

And while the job was a major step forward for women in the aviation industry, it still reeked of the patriarchy. Women couldn't be older than 25 and they had to quit if they got married.

After a three-month trial period, BAT decided to keep the flight attendants permanently and other airlines began hiring their own. For decades, the role was purely a female one, as is evidenced by the fact that the use of "stewardess" hung around until the 1970s, when airlines began hiring men again.

Church would only continue working for BAT for another 18 months, when a car crash ended her career. She later earned a nursing degree and served in the Army Nurse Corps during World War II. She died in 1965 from injuries sustained in a horseback riding fall, one month after she received the Amelia Earhart Memorial Award for her contribution to aviation.

Friday's milestone anniversary comes at a time modern flight attendants face an uncertain and potentially dangerous future. The head of the Association of Flight Attendants-CWA union last month called on the Trump administration to ban all leisure flights until the novel coronavirus has been contained.

"While this global system is integral to our modern economy, its essential inter-connectedness also provides a convenient pathway for opportunistic pathogens to hitch rides on unsuspecting crewmembers and travelers and spread all over the world," AFA International President Sara Nelson wrote in a letter to the administration.

"As some of the most frequent travelers, flight attendants feel a deep responsibility to ensure that our workplace risks of acquiring and spreading communicable diseases are minimized as much as possible."

Most flight attendants have held onto their jobs despite a sharp decline in air travel in recent months, thanks to a government bailout. Under the terms of the aid, airlines are required to keep employees on the payroll until at least October. After that, executives predict up to one-third of the sector's job could disappear.

"We have a lot of cash today, but we burned through about almost a billion dollars in the month of April as an example," Southwest Airlines CEO Gary Kelly told CNN this week.

Helene Becker, an airline analyst with financial services firm Cowen, said the industry could lose as many as 105,000 jobs out of roughly 750,000 pilots, flight attendants, baggage handlers and mechanics.

Bass Pro Shops marketing manager David Smith (R) carries a box of donated face masks into Mercy Health in Chesterfield, Mo., on May 13. The company is donating 1 million FDA-approved ASTM Level 1 Procedure Face Masks to healthcare workers and first responders working on the front lines of the pandemic. Photo by Bill Greenblatt/UPI |

License Photo