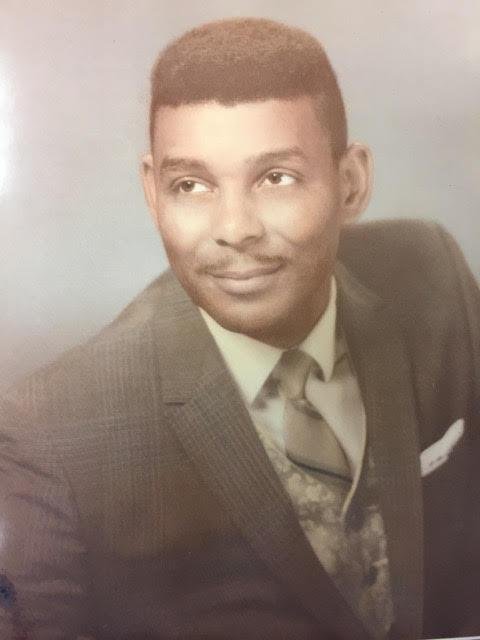

1 of 2 | Charles Greenlee, one of the Groveland Four members, is shown here in an undated photo. After 12 years in p prison for a wrongful conviction, he moved to Nashville, Tenn. where he ran an electrician/HVAC business until his death in 2012. Photo courtesy of Carol Greenlee

Dec. 25 (UPI) -- Advocates and family members of the Groveland Four, a group of young black males wrongly convicted of raping a white woman in 1949, have renewed hope for justice after several high-profile Florida politicians from both parties this month called for a pardon.

On Thursday, Florida Governor-elect Ron DeSantis, who will have the power to grant the pardons once he takes office in January, said "justice was miscarried" for Earnest Thomas, Samuel Shepherd, Walter Irvin and Charles Greenlee, who was 16 at the time of his arrest.

Shepherd, Irvin and Greenlee were arrested and beaten until the latter two confessed.

Thomas was killed by Lake County Sheriff Willis McCall at the time of his arrest. Family members were arrested and threatened. White mobs rioted, burned down Shepherd's home and demanded that the suspects be lynched. And during the trial, defense attorneys weren't allowed to bring in witnesses or evidence to prove innocence. Eventually, an all-white jury convicted the Groveland Four and sentenced the two adults to death and Greenlee to life in prison.

Later, after the first trial, McCall shot and killed Shepherd while transferring him to another jail, claiming he tried to escape. During that incident, he also shot Irvin three times, including once in the neck as he lay on the ground. Irvin survived the shooting and told federal investigators that he and Shepherd hadn't tried to escape. The shooting, as well as the shooting that killed Thomas, were considered justified by authorities.

The Groveland Four have died since the controversial 1949 case, but in his statement, DeSantis said: "Seventy years is a long time to wait, but it is never too late to do the right thing."

The incoming governor's words come after Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., gave a speech on the Senate floor Wednesday calling for a pardon. And earlier last week, Florida Agriculture Commissioner Nikki Fried, the top elected Democrat in the state, also urged DeSantis to issue a pardon, which she said is long overdue since a bipartisan group of state lawmakers passed a resolution in 2017 that exonerated the four men.

This isn't the first time a pardon seemed to be inevitable. In April 2017, the Florida Senate passed a resolution that included a "heartfelt apology" to the families of the Groveland Four, admitted that their convictions "caused by the criminal justice's failure to protect their basic constitutional rights' and urged Scott Florida Gov. Rick Scott to issue a pardon.

So far, Scott, who will become the junior senator of Florida after beating Democrat incumbent Sen. Bill Nelson in November, has so far refused to pardon the Groveland Four. But with the resurgence in support for a pardon from other state lawmakers, including DeSantis, the advocates and family of the Groveland Four are optimistic that a pardon will happen soon.

"I've always believed that the story of the Groveland Four was not a matter of right vs. left, but rather right vs. wrong," said Gilbert King, the author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Devil in the Grove, which details the case and aftermath. "So I'm inspired by how politicians in Florida have come together, in a bipartisan manner, to recognize and correct the record of this gross injustice. This case has always been about 'Equal Justice Under Law,' which is a societal ideal that all Americans can agree on."

For the family of the Groveland Four, the potential for a pardon offers the opportunity for closure that has eluded several families for decades, causing deep pain that hurt too much to talk about.

'It rips your heart out as a child'

When Carol Crawley was born, her father, Charles Greenlee, had just begun serving a life sentence.

"If you're a child and you're with your friends and they're with their families, their fathers and they're doing things together and you're constantly asked, 'Where's your father? Is he coming?'" Crawley said. "You as a child have to answer that question. And then when you get older and the question is still being asked and now you understand what rape means. Good Lord, it rips your heart out as a child."

Crawley said the experience made her withdraw within herself out of shame and anger.

"It made me not want to be a part of or think twice before joining a group. It's very hard for a child to have to explain or even talk about an issue like that. That's an adult issue. It shouldn't be on a child," she said.

After 12 years in prison, Greenlee's sentence was commuted to life in prison with parole, which he got in 1961. He left Florida and joined his family in Nashville, Tenn., where his brother had a job waiting for him as a Hearst driver for a funeral home.

While in prison, Greenlee learned the electrician trade and, upon his release, built a popular HVAC business in Nashville. Crawley remembers him as a hard-working man who was always doing service calls, but never talked about his time in prison or the events that put him there. And it wasn't until she was 40 when she had the nerve to finally ask him about it.

"He dropped his head and he said he knew that this day was gonna come. He dreaded it but he knew eventually he was gonna have to say something to me," Crawley said. "And I could tell that it was difficult for him to even talk about that because it brought up other issues like how he was tortured and how he was treated when he was in prison."

Crawley said her father said he would rather forget the past and focus on his family, which is why he never talked about the incident, much less talked about getting a pardon. But there was another reason. He worried that speaking out about the incident and fighting for justice could bring repercussions.

"Some of those people and their families are still alive," he told Crawley.

Greenlee went on about his life until it ended in 2012 at the age of 79.

To this day, she smiles thinking about when, on his rare days off, he'd take her into the woods to practice archery.

"He could hit the bullseye every time and then laugh at me because I couldn't even hit the target. That was our time together," she said.

And once in a while on Saturday evenings, after finishing his work orders, he'd catch an episode of WWF wrestling.

"He knew the wrestling was fake but he just loved it," Crawley said.

Although Greenlee didn't try to get a pardon during his lifetime, Crawley has no doubt he would be happy to know it could be coming soon.

"He would be overwhelmed just as I am," she said. "Who wouldn't want their name to be cleared?"

'He never shed a word about it'

James Shepherd was the oldest brother of Samuel Shepherd. When Samuel was arrested in 1949, police also arrested James because they alleged Samuel and Irvin were driving his car, and their parents, for no clear reason other than intimidation and to prevent them from giving statements to the press and NAACP. And when white mobs wreaked havoc in the area, they burned down the Shepherds' home.

The trauma for the Shepherd family continued two years later in 1951 when McCall killed Samuel in a shooting that many believe was a premeditated murder.

"My dad didn't really talk about it," said Vivian Shepherd, James' daughter. "I saw a picture and I asked who it was. And my dad said, 'That was my brother. He died. He was shot and killed. I don't want to talk about it.'"

"He would just not talk about it to us. He never shed a word about it," she added.

Growing up, Vivian was aware of the Groveland Four case from family chatter here and there, but due to her father's insistence on keeping quiet about it, she didn't know many of the details until she did her own research.

Once she found out how hard-hit her family had been by the case, she gained some insight into her father, who died in 1989.

Vivian remembers him as a caring man who helped family and neighbors, but also kept to himself a great deal. A talented mechanic who could sometimes diagnose a car's trouble simply by listening to the engine, he threw himself into work.

"It gave me some understanding about why my father worked all the time," Vivian said. "I remember him doing long hours at work or out in his garage, where he's be welding or working on cars. Late hours, until 11 or 12 at night, he'd be in his garage. And talking to some of my siblings, we think that was a way of him dealing with those issues."

"Men lost their lives over a lie," she said. "And it not only ended their lives, it altered our lives."