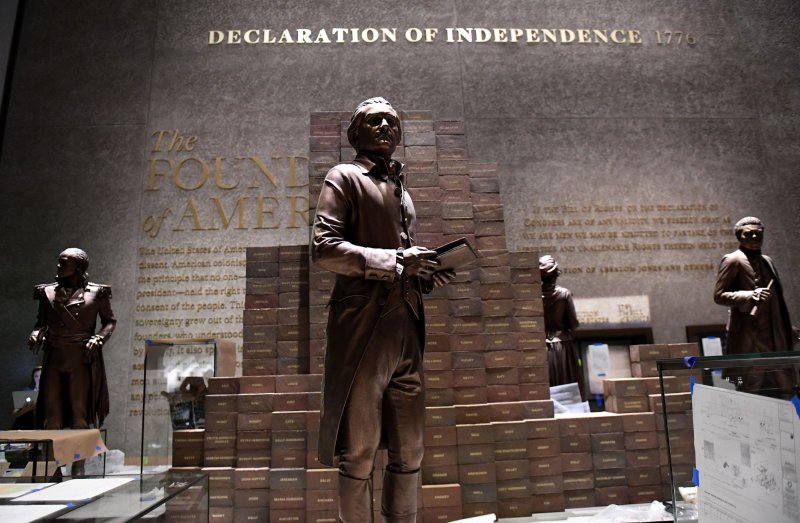

1 of 7 | President Thomas Jefferson is shown with a wall of bricks to denote each of his slaves as part of the new Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. The 400,000-square-foot museum on the National Mall opens to the public this weekend. Photo by Pat Benic/UPI |

License Photo

There's a long and convoluted creation story for most important civic institutions, but the tale behind the National Museum of African American History and Culture is in a category of its own.

This backstory is easy to read as a metaphor for the very narrative the newest part of the Smithsonian wants to tell, because the museum's progress toward its triumphant opening has been set back so often by enervating experiences familiar to black Americans: Passive aggression, overt discrimination, willful ignorance, simple neglect, ethnocentrism, broken promises, financial shape-shifting and political pandering, to name a few.

On top of that is the very length of the tale, which sounds like hyperbole: It's been 101 years since the first public campaign began for a place in Washington memorializing the African-American experience. (For comparison, it's not yet been 400 years since enslaved Africans first arrived here.)

During the last century, waves of political inertia and long stretches of gridlock were interspersed with bursts of seeming accomplishment. And the fault lines in the many sporadic debates have been less partisan than the conventions of today would suggest.

Those are patterns emblematic of the way the Washington policymaking process works much of the time — although rarely do members of 50 different Congresses, and 15 presidents, have a hand in speeding, slowing, ignoring and ultimately establishing a prominent new government enterprise.

"The story of this place really represents what the African-American experience has been," said Michelle Wilkinson, the Smithsonian curator who created a modest exhibition about the making of the museum in time for this weekend's opening. "It's about the long road of challenges to be recognized and valued as a central component of the nation."

The birth of the effort

The story begins in the summer of 1915, at celebrations marking the 50th anniversary of the end of the Civil War. A group of Union veterans had formed the Committee of Colored Citizens, which financed an encampment where their colleagues could stay in segregated Washington before joining the parade up Pennsylvania Avenue. (Black soldiers were excluded from the original triumphant march in 1865.)

Like any savvy advocacy organization of today, the group sought to leverage its initial success into something more ambitious — in this case, by raising money to start an allied group, the National Memorial Association, to lobby for creation of an institution sounding remarkably like what's come to pass:

"A fitting tribute to the Negro's contributions and achievements, and which would serve as an educational center giving inspiration and pride to the present and future generations that they may be inspired to follow the examples of those who have aided in the advancement of the race and nation."

Chapters working to realize that mission statement were eventually formed in all 48 states, but legislation to authorize the project foundered for more than a decade. Lawmakers mainly cited cost as their objection, but profoundly different historic and racial sensibilities also played a part. A national monument to the just-concluded World War I was a higher political priority, for example. And the Senate of 1923 actually voted to pay for a statue "in memory of the faithful slave mammies of the South" near the new Lincoln Memorial.

The first breakthrough came in the lame-duck session of the all-white 70th Congress, in early 1929, under the stewardship of Republican Rep. Leonidas C. Dyer of St. Louis, famous in his day for crusading without success to make lynching a federal crime. The compromise bill he got cleared, which President Calvin Coolidge signed on his final day in office, authorized a museum and gave a new presidential commission authority to spend $50,000 on planning — but only after finding $500,000 in donations.

Herbert Hoover named the 12 panel members, but the onset of the Great Depression soon made their ambitious fundraising goal a nonstarter. (The president rejected the commission's idea to fund the building with $300,000 in payments never claimed by black Civil War soldiers plus another $1.3 million, the estimated loss incurred by African-Americans in the collapse of the Freedman's Bank during Reconstruction.)

Franklin D. Roosevelt abolished the languishing commission in 1933 and turned over its duties to the Interior Department. The next year, he rebuffed the department's $12,500 request for fundraising expenses, and a year after that, he rejected the idea of making the museum a Works Progress Administration construction project.

Idea languishes

The following three decades were the most fallow in this prehistory. But more than a dozen bills proposing a black history museum, cultural center or national memorial were introduced in Congress after the 1968 assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. None passed, despite high-profile lobbying (including congressional testimony) by prominent African-Americans including novelist James Baldwin and baseball legend Jackie Robinson.

Complicating the drive was the creation of dozens of local museums of black art, history and culture, which viewed the creation of a national institution as a threat to their fundraising and artifact acquisition. But at the behest of Tommy Mack, the proprietor of D.C.'s Tourmobile bus company, who had grand ambitions to finance a national museum, Democratic Rep. Mickey Leland of Texas got Congress in 1986 to adopt a nonbinding resolution declaring support for putting such a building on the Mall.

The next, climactic step took nine tries over 18 years.

Soon after John Lewis — whose iconic standing in the civil rights movement would earn him pride of place in any African-American museum — arrived as Atlanta's new Democratic congressman in 1987, he declared such a place should be part of the Smithsonian Institution.

That effectively sealed the museum's future as a federal facility. Deliberations over where it should be and how it should be financed would drag out for much longer.

Mainly to appease lawmakers concerned about giving black America too much prominence relative to other aspects of the national story — but also to hold down costs — proposals were floated for establishing the newest part of the Smithsonian in a wing of the National Museum of American History, having it share space with the new National Museum of the American Indian or repurposing the 19th century Arts and Industries Building.

After Lewis endorsed that last compromise, it passed the House on a voice vote in 1993 — the first of his four museum authorization bills to get through. But the measure died in the Senate the next year, mainly because of diehard opposition from zealous conservative Republican Jesse Helms of North Carolina.

"Once Congress gives the go ahead for African-Americans," he asked rhetorically on the floor, "how can Congress then say no to Hispanics, and the next group, and the next group after that?"

Project solidifies

After unsuccessful attempts in the next three Congresses, Lewis won another victory at the end of 2001 because he'd formed a coalition with Republican Conference Chairman J.C. Watts Jr. of Oklahoma, then the only black person in the House majority, and GOP Sen. Sam Brownback of Kansas (now the state's governor.)

They all tended to use the same phrase — "a catalyst for reconciliation" — in describing the would-be museum's mission. And with the Smithsonian itself at last behind the concept of a stand-alone facility, the group pushed through a law establishing a commission that would propose where it should be located and how it should be funded.

Fifteen months later, the panel recommended construction at a highly prominent spot, on the greensward where Constitution and Pennsylvania avenues intersect, with half of the money from the Treasury and half from corporate or individual donations.

Within months, the crucial authorizing legislation was embraced by the Hill's entire GOP leadership and sailed through Congress almost anticlimactically. And it embodied a final compromise that dictated the size and shape of today's museum.

The law codified the 50-50 funding formula the blue-ribbon group proposed, which will commit Congress to appropriating about $270 million overall.

But the statute rejected the panel's proposed site at the foot of Capitol Hill and told the Smithsonian's regents to choose from four others — including the five acres, just northeast of the Washington Monument, where the 400,000-square-foot, three-tiered building covered with bronze panels now stands. (The spot was chosen in 2006 and the architects in 2009; Barack Obama, the first black president, presided at the groundbreaking in 2012 with former first lady Laura Bush, a member of the museum's board, in attendance.)

It had fallen to President George W. Bush to sign the law assuring that the museum would be built. The measure cleared the Senate by voice vote a week before Thanksgiving 2003, a day after the House voted 409-9 for the bill.

Four of the dissenters, all Republicans, are still in Congress: Walter B. Jones of North Carolina, Jim Sensenbrenner of Wisconsin, Sam Johnson of Texas and Jeff Flake of Arizona, who's now a senator.

Jones declined several requests for comment. The others recently defended those 13-year-old votes as statements in favor of fiscal restraint and in no way in opposition to memorializing African-American history and culture.

"Fiscal concerns aside, Congressman Johnson looks forward to attending the opening ceremony," his spokeswoman said.

"This museum is sure be one of the nation's finest and I have immense respect for its mission," Flake said. "I look forward to visiting it with my wife and kids soon."

Get breaking news alerts and more from Roll Call on your iPhone or your Android.