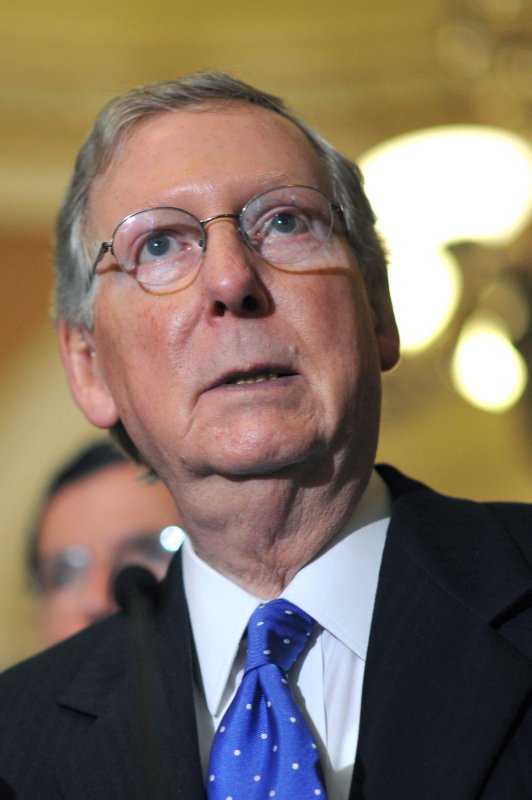

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., speaks to reporters prior to a Senate vote on the House bill that would continue funding the government while defunding Obamacare on Sept. 24, 2013. -- UPI/Kevin Dietsch |

License Photo

WASHINGTON, Dec. 15 (UPI) -- Senate Republicans, after asking for it earlier, last week received a piece of the action when the U.S. Supreme Court hears argument on the scope of a president's recess appointment power -- or least President Obama's exercise of that power.

In an order Dec. 9, the justices said a lawyer for Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell and 44 other Republicans could have one-fourth of the hour set aside for argument Jan. 13. The National Labor Relations Board and the administration get half of the hour, while the company that challenged Obama's appointments to the board gets the final one-fourth.

The divided argument in the recess appointment power case is scheduled only a couple of weeks before the deadline at the Supreme Court for friend-of-the-court briefs in the challenge to the Affordable Care Act's contraception mandate.

In other words, in the next couple of months the Supreme Court is caught in a vortex of the struggle for power between Democrats and Republicans.

To recap the recess appointment dispute, the justices have asked the parties to review "whether the president's recess-appointment power may be exercised when the Senate is convening every three days in pro forma sessions" in which no business is done.

Presidents since George Washington have made recess appointments when the Senate is not in session. At the heart of the current dispute is exactly when the Senate is in session.

As Democrats had done previously, Senate Republicans kept the Senate in pro forma session to avoid recess appointments. Obama opted to challenge the practice in January 2012 when some Republican senators were holding pro-forma sessions while the Senate technically was on a 20-day recess.

When a frustrated Obama moved ahead with three appointments to the National Labor Relations Board that Republicans considered too labor-oriented, Noel Canning, a Pepsi bottling and distributing company in Washington state and a division of Noel Corp., took the board to court after it ruled against the company in a union dispute, challenging the board's legitimacy.

The case eventually landed in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. A three-member appeals court panel ruled the NLRB's decision was invalid "as it did not have a quorum" because of the invalidity of the recess appointments.

The administration then successfully asked the Supreme Court for review, but eventually replaced the three controversial nominees.

McConnell and the 44 other Republican senators filed their own brief to the Supreme Court in late November.

The brief cites the Constitution, which "makes the Senate's 'advice and consent' a condition precedent to the appointment of federal officers, except for inferior officers exempted by Congress. ... The Recess Appointments Clause ... permits the president to 'to fill up all vacancies that may happen during the recess of the Senate, by granting commissions which shall expire at the end of their next session.' But the Senate itself is empowered to 'determine the rules of its proceedings,' including when and how to hold sessions and to adjourn."

Obama made the three NLRB appointments "on Jan. 4, 2012, while the Senate's records show that it convened sessions every three days."

The president's "claim that the [D.C.] court of appeals' decision upsets the constitutional structure and deprives the president of power the framers granted has matters exactly backwards," the Republican brief said.

"It is the president who, by making the January 2012 recess appointments that the decision below invalidated, usurped two powers the Constitution confers on the Senate -- and claimed a unilateral appointment authority that the framers intentionally withheld. Article II gives the Senate a veto over federal appointments, requiring its 'advice and consent' for appointments to all principal offices [and inferior posts not exempted by Congress]. And although the framers allowed the president to fill 'vacancies that may happen during the recess of the Senate' with temporary commissions ... they reserved to the Senate plenary power over 'all matters of method' ... including [with few, enumerated exceptions] when and how to hold sessions and when to adjourn."

The brief contended Obama's "January 2012 appointments eviscerated both of these Senate prerogatives. By purporting to appoint principal officers without the Senate's approval, the president contravened the advice-and-consent protocol. As the court of appeals held, those appointments cannot be justified by the recess appointments clause without distorting that provision's text and purpose beyond recognition: The appointments were made neither during 'the recess of the Senate,' but instead in an intrasession adjournment, nor to fill 'vacancies that ... happen[ed] during the recess,' but to pre-existing openings."

The January 2012 appointments are invalid, the brief argued, "unless the president has power to declare those sessions nullities.

"He does not. The Constitution vests authority to prescribe Senate procedure in the chamber itself. And its official account of its activities is controlling. The executive's contrary claim has no foothold in the Constitution's text or structure, and if upheld would severely undermine the separation of powers."

A separate brief filed by U.S. Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, largely agrees with McConnell's, but adds that for "purposes of the president's recess appointment power, a recess exists only when the House and Senate agree that the Senate is in recess."

In its own earlier brief, the NLRB and the administration argue, "The recess appointments clause authorizes the president to make temporary appointments 'during the recess of the Senate, by granting commissions which shall expire at the end of their next session. ... That unqualified reference to 'the recess of the Senate' attaches no significance to whether a recess occurs during a session or between sessions."

If the Supreme Court upholds Obama's appointments, it "will not vitiate the Senate's powers or the ordinary process of advice and consent," the administration said. "The recess appointments were only temporary; the commissions were to 'expire at the end of [the Senate's] next session.' ... The Senate retained authority to vote on the president's nominees when it returned. More fundamentally, the Senate retains the choice it has always had: to remain 'continually in session for the appointment of officers' ... thereby removing the constitutional predicate for the president's recess appointment power, or to cease temporarily the conduct of business [and potentially leave the capital] knowing that the president may make temporary appointments during that period."

The Senate "cannot choose to do both at the same time," the administration said.

Obama's recess appointments seem to have few defenders and many critics.

"President Obama's move [to make recess appointments in January 2012] drew substantial criticism and sparked a constitutional debate over the recess appointments clause," the Heritage Foundation's blog The Foundry said. "Until that point, no president had ever made a recess appointment when the Senate was convening in pro forma sessions every three days. Indeed, for nearly 100 years, the president and Senate had agreed that no recess appointments would be made when the Senate was out for less than 10–20 days."

The conservative blog adds, "If the historical line of 10–20 days no longer applies, what is the limiting principle for a 'recess'? Should senators be concerned that the president could make recess appointments when they go home for the evening? Or during a lunch break?"

In the Legal Times blog, veteran Supreme Court reporter Marcia Coyle sums up both sides of the argument, including the administration's.

"Under a unanimous consent order of the Senate, the second session of the 112th Congress began with a period of nearly three weeks, from Jan. 3 to Jan. 23," Coyle wrote. "in which the Senate had provided that 'no business [was to be] conducted,' and during which no senators were required to attend other than one senator who gaveled each pro forma session in and out."

"In view of the Senate's explicit cessation of business for that extended period, the president determined that the Senate was in recess," Solicitor General Donald Verrilli told the justices in a petition. "Accordingly, on Jan. 4, 2012, the president invoked the Recess Appointments Clause and appointed three new members to fill the vacant seats on the board."

The Heritage Foundation blog points out three federal appeals courts have ruled against the January 2012 appointments.