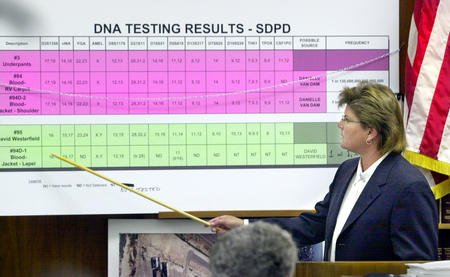

SAN DIEGO, June 20 (UPI) -- DNA analyst Annette Peer explains her DNA testing on various items of evidence at the trial of David Westerfield in San Diego on June 20, 2002. Westerfield was convicted in the kidnapping and murder of 7-year-old Danielle van Dam, and is on death row. --. jaf/le/Nelvin Cepeda UPI |

License Photo

WASHINGTON, Nov. 17 (UPI) -- The case of Ryan Ferguson, the Missouri man freed after spending 10 years behind bars for a murder he says he didn't commit, shows the nation's justice system, one of the fairest in the world, occasionally convicts the innocent, puts them in prison and throws away the key.

Does the U.S. Supreme Court give a damn?

Ferguson improbably was convicted on the "repressed memories" of a friend for the 2001 killing of Columbia (Mo.) Daily Tribune Sports editor Kent Heitholt in the newspaper parking lot as Heitholt was leaving work early in the morning.

The friend recanted at trial and another witness putting Ferguson at the scene also recanted. He was not connected to fingerprints, bloody footprints and hair found at the crime scene.

Ferguson, now 29, was sentenced to 40 years. He was finally freed last week. The friend, whose "repressed memories" of participating in the crime with Ferguson surfaced in dreams years after the killing, remains in prison.

A Missouri appeals court said Ferguson "has established the gateway of cause and prejudice, permitting review of his procedurally defaulted claim that the state violated [the U.S. Supreme Court's 1963 ruling in] Brady vs. Maryland ... by withholding material, favorable evidence of an interview with Barbara Trump, the wife of Jerry Trump, one of the state's key witnesses at trial.

"The undisclosed evidence was favorable because it impeached Jerry Trump's explanation for his ability to identify Ferguson," the appeals court said. "The undisclosed evidence was material because of the importance of Jerry Trump's eyewitness identification to the state's ability to convict Ferguson, because the evidence would have permitted Ferguson to discover other evidence that could have impacted the admissibility or the credibility of Jerry Trump's testimony, and because of the cumulative effect of the non-disclosure when considered with other information the state did not disclose.

"The undisclosed evidence renders Ferguson's verdict not worthy of confidence."

After the ruling, the Missouri Attorney General's Office said, for the time being, it would not pursue any further action against Ferguson.

Is Ferguson's case an anomaly?

Not according to The Innocence Project, "a national litigation and public policy organization dedicated to exonerating wrongfully convicted individuals through DNA testing and reforming the criminal justice system to prevent future injustice." The project is affiliated with the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University in New York City.

So far, the project's lawyers have freed more than 300 prisoners based on DNA testing, including 18 on death row.

"These people served an average of 13 years in prison before exoneration and release," the project says in its mission statement. That mission, the project website says, "is nothing less than to free the staggering numbers of innocent people who remain incarcerated and to bring substantive reform to the system responsible for their unjust imprisonment."

The Death Penalty Information Center, a non-profit headquartered in Washington that opposes capital punishment, says more than 115 people in 25 states have been released from death row because of innocence since 1973.

As for whether the U.S. Supreme Court gives a damn, the justices ruled in 2011 that prisoners have a right to sue under federal civil rights law when claiming that a state's DNA procedures are too restrictive.

In that case, death row inmate Henry W. Skinner consistently maintained his innocence. His imminent execution was stayed at the last hour by the Supreme Court in 2010.

Skinner was sentenced to death for the 1993 murders of his girlfriend and her two adult sons in the Texas Panhandle city of Pampa on New Year's Eve. The girlfriend, Twila Busby, was strangled and beaten with an ax handle and her mentally disabled sons, Elwin Caler and Randy Busby, were stabbed.

Skinner, who worked as a paralegal at the time of his arrest, asked for new DNA testing on blood found on knives at the murder scene and material beneath the woman's fingernails, as well as rape kit samples.

More than six years after his conviction, a new Texas law allowed prisoners to gain post-conviction DNA testing in limited circumstances. The Texas courts denied Skinner's request for DNA testing, and federal courts said Skinner could not ask for the testing under federal civil rights law.

But in a 6-3 majority opinion written by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the Supreme Court said there was federal court subject-matter jurisdiction over Skinner's complaint, and the claim he made is recognizable under civil rights law.

The opinion noted Skinner only was challenging the Texas courts' interpretation of the state DNA statute.

Ginsburg said in an earlier similar case out of Alaska, the Supreme Court only assumed that there was a right to make such a claim under civil rights law, but did not specifically rule that there was. The 2011 ruling nails down that right.

Though Skinner won the right to sue under civil rights law, DNA testing more firmly implicated him in the murder, and he remains on death row. However, his case gives other death row inmates more elbow room to demand DNA testing under state law.

The Supreme Court's precedents on prisoners who claim innocence -- "actual innocence" rather than legal innocence, based on the contention they did not commit the crime -- is uneven.

In 1993's Herrera vs. Collins, the late Chief Justice William Rehnquist said for the 6-3 majority a Texas death row inmate "urges us to hold that this showing of innocence entitles him to relief in this federal habeas [constitutional review] proceeding. We hold that it does not."

The inmate's "contention that the 14th Amendment's due process guarantee supports his claim that his showing of innocence entitles him to a new trial, or at least to a vacation of his death sentence, is unpersuasive." There was no reason, Rehnquist said, to push aside a Texas requirement that a new trial motion based on new evidence must be made within 30 days of the "imposition or suspension of a sentence ... in light of the Constitution's silence of new trials" based on newly discovered evidence.

In a separate and bitter dissent, the late Justice Harry Blackmun said the execution of a person "who can show that he is innocent comes perilously close to simple murder."

The Texas inmate, Leonel Torres Herrera, guilty of murdering two police officers with plenty of evidence against him, was executed.

The high court does not decide on guilt or innocence and at least two justices have said "actual innocence" is not even relevant, United Press International reported four years ago.

In a 2009 dissent after the other justices granted a new evidence hearing for a Georgia death row inmate, Justice Antonin Scalia, joined by Justice Clarence Thomas, wrote: "This court has never held that the Constitution forbids the execution of a convicted defendant who has had a full and fair trial but is later able to convince a [constitutional] court that he is 'actually' innocent. Quite to the contrary, we have repeatedly left that question unresolved, while expressing considerable doubt that any claim based on alleged 'actual innocence' is constitutionally cognizable."

In June 2009, the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 along its ideological divide that convicts, even death row inmates, had no constitutional right to access DNA evidence or other biological evidence held by the states, even if, only for argument's sake, you assume access can be reached through the federal civil rights statute.

The case involved a man named William Osborne, convicted of sexual assault and other crimes in Anchorage, Alaska. After the assault, a prostitute had been shot in the head, beaten with an ax handle and left for dead. He was sentenced to 26 years.

Years later, he asked for access to DNA evidence so he could have it tested at his own expense. Eventually, a federal appeals court agreed he had a constitutional right to the DNA evidence. The narrow Supreme Court majority disagreed.

Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the majority opinion, "DNA testing ... has the potential to significantly improve both the criminal justice system and police investigative practices. The federal government and the states have recognized this, and have developed special approaches to ensure that this evidentiary tool can be effectively incorporated into established criminal procedure -- usually but not always through legislation."

Forty-four states and the federal government have laws allowing inmates access to DNA and other biological evidence.

"Against this prompt and considered response ... William Osborne proposes a different approach: the recognition of a freestanding and far-reaching constitutional right of access to this new type of evidence. ... This approach would take the development of rules and procedures in this area out of the hands of legislatures and state courts shaping policy in a focused manner and turn it over to federal courts applying the broad parameters of the [Constitution]."

Justice John Paul Stevens, now retired, dissented. "The state of Alaska possesses physical evidence that, if tested, will conclusively establish whether ... William Osborne committed rape and attempted murder. If he did, justice has been served by his conviction and sentence. If not, Osborne has needlessly spent decades behind bars while the true culprit has not been brought to justice. The DNA test Osborne seeks is a simple one, its cost modest and its results uniquely precise. Yet for reasons the state has been unable or unwilling to articulate, it refuses to allow Osborne to test the evidence at his own expense and to thereby ascertain the truth once and for all."

Roberts and Stevens captured the essence of both sides of the ongoing debate on post-conviction remedies, UPI reported in 2010.

On one side, Roberts and his fellow conservatives warn at some point, judicial proceedings have to be final, and opening the floodgates of judicial review might return the justice system to the days when death row inmates and others delayed their sentences for decades with claim after claim, despite the overwhelming evidence that convicted them.

After all, Congress, fed up with endless federal appeals, enacted the Anti-terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act in 1996 to limit habeas review.

On the other side, Stevens and his fellow liberals made the practical argument: If a DNA test or rape kit test can make a conviction even more certain, or expose a miscarriage of justice, why not do it?

Such divisions probably will continue. How do you effectively punish the great mass of the guilty without damning the innocent few?

The U.S. Supreme Court is the nation's highest court of review, not a trier of fact. The letters carved on the front facade of the Supreme Court building, across from Congress on Capitol Hill, don't promise "Justice," only "Equal Justice Under Law."