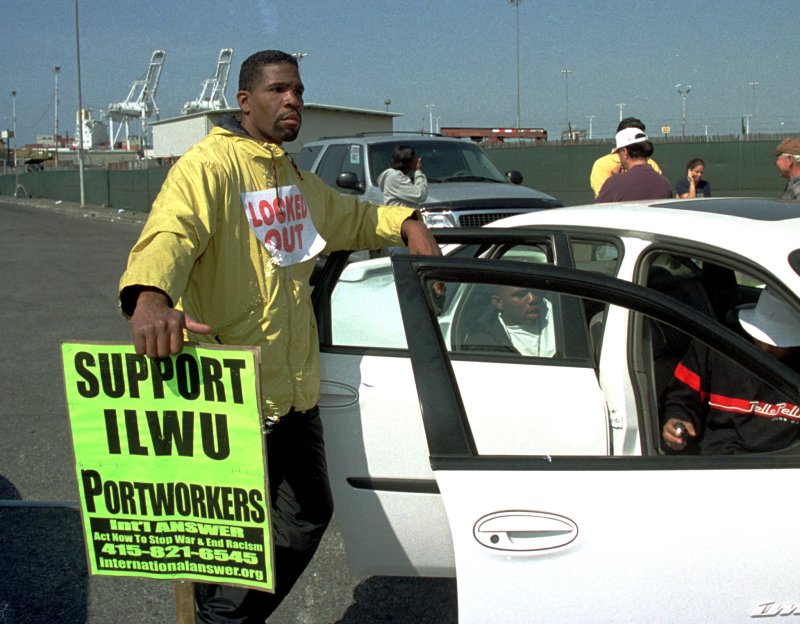

Longshoreman Deandre Whitten listens to a car radio for news of the West Coast lockout of dock workers while picketing at the Port of Oakland in Oakland, Calif., in 2002. An unrelated case before the U.S. Supreme Court may have an impact on how much leeway union workers have when picketing. -- David Yee UPI |

License Photo

WASHINGTON, June 2 (UPI) -- Do the states have the power to protect the right of unions to picket on private property even when a business owner, the property owner, doesn't want them there? The U.S. Supreme Court is scheduled to decide whether it wants to settle the issue when the justices sit in conference behind closed doors Thursday.

The case is not receiving much attention as the Supreme Court is poised to hand down landmark rulings on gay marriage and race in the final month of the term. Those rulings will descend like hammer blows throughout June.

But the picketing case is the kind of dispute guaranteed to raise the hackles of conservatives or liberals, depending on who ends up the loser, the union or the business owner.

The justices can reject the case, leaving the union the victor in the lower court; delay consideration until a future conference; summarily rule in the case, based on high court own precedent; or accept the case for argument next term.

It takes the votes of four justices for the U.S. Supreme Court to accept a case. When review is denied, a justice will sometimes express his or her frustration by writing an opinion in dissent.

An attorney for the United Food and Commercial Workers Union Local 8 told law360.com it is unlikely the U.S. Supreme Court will accept the case -- meaning the lower court victory for the union would stand.

"The First Amendment theory that Ralphs [Grocery Co.] has argued didn't find any takers in the California Supreme Court," Paul More of Davis Cowell & Bowe LLP, who represents the union, told Law360 at the time the petition was filed. "It's a theory that doesn't have any basis in precedent, and we are confident that the [U.S.] Supreme Court will recognize that and won't be interested in this case."

But the National Chamber Litigation Center urged the U.S. Supreme Court to jump into the controversy.

In a brief, the NCLC "urged the [U.S.] Supreme Court to review the California Supreme Court's decision, which held that states may discriminate based on the content of speech when organized labor is the beneficiary," the organization said on its website.

"NCLC argued that states may not give special protection to speech that would otherwise be unlawful, based solely on its content. NCLC pointed out that the California Supreme Court's incorrect decision may have far-reaching consequences. A number of states have enacted statutes similar to the one at issue here [protecting picketing on private property] and if the California Supreme Court's decision stands, it will signal to other state courts that content discrimination is acceptable when organized labor is the beneficiary. Additionally, NCLC argued that this decision also means that private property owners must acquiesce control of their property to that state when state-preferred speech is at issue."

SCOTUSblog's canny founder, Supreme Court litigator Tom Goldstein, has been cited on the website as believing the case "has a reasonable chance of being granted" high court review.

The dispute began in July 2007 shortly after the Ralphs Grocery Co. chain "opened a retail warehouse grocery store under the brand name Foods Co in a modest Sacramento commercial development, 'College Square," the business said in its petition to the high court.

"Shortly after petitioner opened its grocery store in Sacramento, [the] union's agents began picketing on the store's private property [at the entrance to the store, on the apron area, and in the parking lot]," Ralph's said. "The picketing continued five days a week, eight hours each day, for several years."

The petition said the picketers, "varying in numbers from four to eight, marched back and forth in front of the entrance to the store carrying picket signs, speaking to customers, and handing out flyers. ... The picketers walked in a circle near the entrance so that customers could not avoid them as they went into the store."

The picketers "also so positioned themselves in the private parking lot. ... Foods Co customers complained that the picketers harassed them and made them feel uncomfortable."

The petition said the purpose of the picketing, "as the union acknowledges, was to disrupt the store's commercial operations by encouraging customers 'to boycott Foods Co's non-union stores for not adhering to union standards.'"

Ralphs asked the police to remove the union representatives from the Foods Co store property.

"The police refused to intervene without a court order," the company said. "The picketing continued for several years."

When the dispute went to state court, the trial judge refused to act against the union, saying the company had failed to satisfy the requirements in the state code necessary for an injunction against labor picketing. A state appeals court reversed, saying the private property was not a public forum and the two state laws protecting picketing on private property -- the Moscone Act and the section of the code -- violated free speech and constitutional equal protection by giving a labor dispute more protection than speech involving other subjects.

However, the California Supreme Court reversed the state appellate court, ruling the picketing had protection under the Moscone Act and the relevant state code section, and that those laws do not violate the U.S. Constitution's prohibition on content discrimination in the protection of speech.

Ralphs then asked the U.S. Supreme Court for review, requesting it decide whether the Moscone Act and the California code "violate the U.S. Constitution by forcing property owners to open private property to the expressive activities of others based on the content of their speech."

The petition said: "The California Supreme Court's decision contravenes this [Supreme] Court's precedent. The First Amendment and the equal protection clause [of the U.S. Constitution] prohibit a state from singling out a topic of speech for special protection. Indeed, this [Supreme] Court twice has held unconstitutional state laws that favored labor-related speech."

The petition said the California Supreme Court decision conflicts with one in a similar case handed down by a court in Washington.

The state Moscone Act "immunizes labor-related speech -- and only labor-related speech -- from California's trespass law," the petition said. The act prohibits any judicial action against the picketing.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce filed a brief in support of Ralphs.

"The Chamber of Commerce of the United States represents 300,000 direct members and indirectly represents an underlying membership of more than 3 million U.S. businesses and organizations of every size, in every business sector, and from every region in the country," the brief said.

"The chamber has a direct and substantial interest in the important questions presented in this case, namely, whether labor picketers may persist in demonstrating on the privately owned property of a business, against the express wishes of the business owner, and in contravention of the normally applicable law of trespass." the brief said.

"Normally, persistent, disruptive presence on private property against the express wishes of the owner would unquestionably constitute a trespass under California law. ... The California Supreme Court's decision is both significant and incorrect. ... Not even the state's 'commendable' interest in protecting labor picketers can justify content-based regulation of speech."

The union's brief in response said the protection of labor picketing didn't just spring up in California.

"Congress passed the Norris-LaGuardia Act in 1932 to withdraw federal courts from a type of controversy for which many believed they were ill-suited and from participation in which, it was feared, judicial prestige might suffer," the union said.

"The act insulates nine categories of activity from any type of federal-court injunction, including peacefully publicizing a labor dispute," the union said. "For conduct still subject to the courts' jurisdiction, Norris-LaGuardia sets forth requirements that litigants must meet before a court issues an injunction."

The U.S. Supreme Court upheld Norris-LaGuardia shortly after it was enacted.

"Subsequently, many states passed so-called 'Little Norris-LaGuardia Acts,' withdrawing or limiting their state courts' equity jurisdiction in labor disputes," the union said. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld Wisconsin's version of the law in 1937.

Like California's Moscone Act, "Wisconsin's statute stated that 'giving publicity to' a labor dispute and 'peacefully picketing or patrolling' during a labor dispute 'shall be legal.'"

At the time, the U.S. Supreme Court "rejected an equal-protection challenge similar to Ralphs' -- that the state's denial of an injunctive remedy on an unequal basis violated the Constitution," the union said.

California allowed injunctions against picketing up until 1975, often after hearing only one side and using "hearsay," when the Legislature passed the Moscone Act, modeled on the federal Norris-Laguardia law, the union said.

The Moscone Act "does not protect 'breach of the peace, disorderly conduct, the unlawful blocking of access or egress to premises where a labor dispute exists, or other similar unlawful activity."

Four years later, the California Supreme Court interpreted the Moscone Act's scope and upheld it over constitutional challenge in the separate Sears, Roebuck & Co. vs. San Diego County District Council of Carpenters, the union said.

Outside of the Moscone Act, the Legislature passed the relevant section of the state code in 1999. The section "tracks nearly word-for-word section 7 of Norris-LaGuardia. ... Like Norris-LaGuardia, [the code section] states that no court may issue an injunction in a case 'involving or growing out of a labor dispute," unless the evidence meets certain criteria:

-- That unlawful acts have been threatened and will be committed unless restrained or have been committed and will be continued unless restrained.

-- That substantial and irreparable injury to owner's property will follow.

-- "That as to each item of relief granted, greater injury will be inflicted upon complainant [the owner] by the denial of relief than will be inflicted upon defendants [the union] by the granting of relief."

-- That complaining property owner has no adequate remedy at law.

-- "That the public officers charged with the duty to protect complainant's property are unable or unwilling to furnish adequate protection."