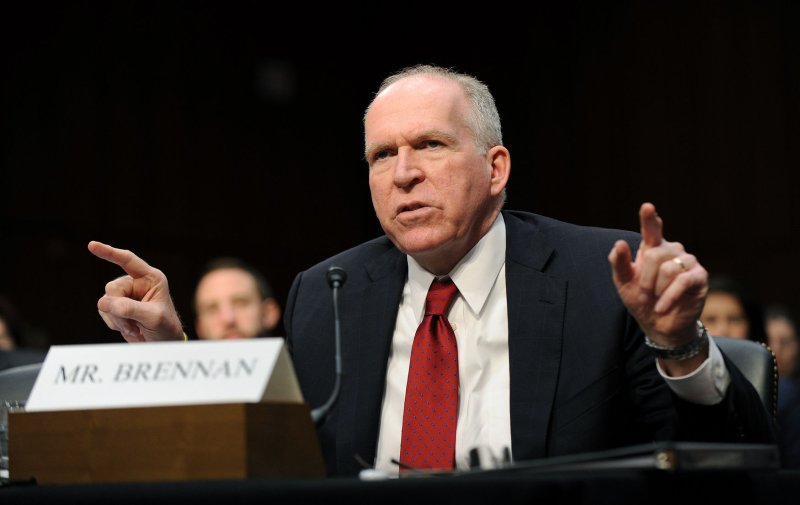

1 of 4 | CIA Director nominee John Brennan testifies during his Senate Foreign Relations confirmation hearing in Washington, DC on February 7. -- UPI/Kevin Dietsch |

License Photo

WASHINGTON, Feb. 17 (UPI) -- Suddenly drones are everywhere -- not in the skies over the United States, as they will be by the thousands in a few years, and not just hovering over foreign battlefields to strike terror in the heart of al-Qaida -- but as the focus of debate in the U.S. Congress and elsewhere.

Inevitably, the U.S. Supreme Court will be asked to determine whether the use of extrajudicial lethal force against those marked as terrorists posing an imminent threat, including U.S. citizens, is constitutional. The court also will be asked to determine how intrusive drones can be when flown over domestic air space by government, law enforcement and private companies.

In what passed for a confirmation hearing, but which actually had all the trappings of a celebrity roast without the bonhomie, John Brennan was grilled Feb.7 by both Democratic and Republican senators on the constitutionality and transparency of the agency's use of drones. Brennan is President Obama's pick to head the CIA.

As Obama's counterterror adviser, Brennan was the principal architect of the administration's targeted killing program against al-Qaida militants, including U.S.-born cleric Anwar al-Awlaki in Yemen.

U.S. officials had linked Awlaki to a number of attempts to kill U.S. citizens, particularly the attempted bombing of a U.S. airliner on Christmas Day 2009.

"We only take such actions to save lives when there is no other alternative to mitigate that threat," Brennan told the Senate confirmation panel, adding officials agonize over trying to limit dangers to civilians.

Brennan said when it was possible to capture a terrorist, the administration has never opted to use lethal force instead.

Asked whether he would consider a special U.S. court to oversee the evidence before drone strikes are launched against U.S. citizens acting as terrorists abroad, Brennan said, "It's certainly worthy of discussion," though protecting Americans has been "an inherently executive branch function."

Brennan said the United States remains "at war with al-Qaida and its associated forces."

Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., a principal critic of the program, said the drone operation shows "unfettered [presidential] power without checks and balances that is so troubling." Wyden asked Brennan whether the administration should "give an individual American an opportunity to surrender" before being targeted as a terrorist.

"Any American that joins al-Qaida will know he has joined an organization that is at war with the United states," Brennan said. He added that any member of al-Qaida "anywhere in the world" has an opportunity to surrender.

Awlaki was killed in a targeted drone strike in Yemen in September 2011. His 16-year-old son was killed a short time later, but it is not known whether he was specifically targeted.

"Now, in response to broad dissatisfaction with the hidden bureaucracy directing lethal drone strikes, there is an interest in applying the model of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act court -- created by Congress so that [foreign and U.S.] surveillance had to be justified to a federal judge -- to the targeted killing of suspected terrorists, or at least of American suspects," The New York Times reported Feb. 8.

Members of the FISA court are appointed by Chief Justice John Roberts. The court conducts "ex parte" proceedings -- meaning only the government has access to its secret, non-adversarial proceedings.

But the Times cited several legal scholars and terror experts who said a "drone court would face constitutional, political and practical obstacles, and might well prove unworkable," though the time may be ripe to create one.

Former U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates, who served in both the Bush and Obama administrations, is among those who support some kind of judicial oversight. He said Feb. 11 an outside check may be needed, "a panel of three judges [like the FISA court] or one judge or something that would give the American people confidence that there was, in fact, a compelling case to launch an attack against an American citizen."

In a sense, Awlaki had his day in court before being killed.

Awlaki was on a U.S. "kill list" believed to contain 20 names of terrorists overseas. In 2010, his father went to federal court in Washington asking for an injunction prohibiting the CIA and the U.S. Defense Department from killing his son.

U.S. District Judge John Bates dismissed the suit, saying Awlaki's father lacked standing, and said targeted strikes were a political issue not a judicial one.

"This court does not hold that the executive [the president] possesses unreviewable authority to order the assassination of any American whom he labels an enemy of the state," Bates ruled. "Rather, the court only concludes that it lacks the capacity to determine whether a specific individual in hiding overseas, whom the director of national intelligence has stated is an 'operational' member of [al-Qaida on the Arabian Peninsula], presents such a threat to national security that the United States may authorize the use of lethal force against him."

Bates, a George W. Bush appointee, said Awlaki could come to court to state his case, JewishWorldReview.com reported, but, "No U,S. citizen may simultaneously avail himself of the U.S. judicial system and evade U.S. law enforcement authorities."

The website report said Bates' ruling cleared "the way for the Obama administration to conduct the targeted killing -- without judicial oversight."

Others are attempting to define the moral, rather than the legal, parameters of the overseas drone program.

An opinion published in the conservative Commentary magazine Feb. 6 points out Obama, in a May 2008 speech, said the war against al-Qaida must be carried out "with an abiding confidence in the rule of law and due process; in checks and balances and accountability."

The president said he had ended enhanced interrogation techniques like waterboarding, and that the Bush administration "over the last eight years established an ad hoc legal approach for fighting terrorism that was neither effective nor sustainable -- a framework that failed to rely on our legal traditions and time-tested institutions, and that failed to use our values as a compass."

Writer Peter Wehner said it's not always easy to "navigate the murky waters of law, morality, war and terrorism, at least when you're in the White House and have an obligation to protect the country from massive harm."

The White House has released a U.S. Justice Department "white paper" to justify drone strikes that critics say is vague and too permissive.

Wehner conceded "there is a serious argument to be made that during wartime targeting terrorists, including Americans, with drones is justified. But that justification probably best not come from someone who has spent much of the last half-dozen years or so sermonizing against waterboarding, accusing those who approved such policies of trashing American ideals and shredding our civil liberties, and portraying himself as pure as the new-driven snow. Because any person who did so would be vulnerable to the charge of moral preening and moral hypocrisy."

On the domestic side, U.S. News & World Report said last year some analysts estimate "there may be as many as 30,000 unmanned drones operating in the United States by 2020 for uses such as wildfire containment and surveillance, law enforcement and surveying."

The Federal Aviation Administration said Friday that 327 of the 1,428 permits issued since 2007 are active. U.S. Customs and Border Protection is the largest user in the federal government with 10 Predator-sized aircraft patrolling the borders with Mexico and Canada.

A report released earlier this month by the non-partisan Congressional Research Service raises a number of questions.

The CRS report said under the FAA Modernization and Reform Act last year, "Congress has tasked the Federal Aviation Administration with integrating unmanned aircraft systems, sometimes referred to as unmanned aerial vehicles or drones, into the national airspace system by September 2015."

The report said the act makes safety a primary concern, but "it fails to establish how the FAA should resolve significant, and up to this point, largely unanswered legal questions."

Would a drone overflight in the United States "constitute a trespass? A nuisance? If conducted by the government, a constitutional taking? In the past, the Latin maxim cujus est solum ejus est usque ad coelum (for whoever owns the soil owns to the heavens) was sufficient to resolve many of these types of questions, but the proliferation of air flight in the 20th century has made this proposition untenable. Instead, modern jurisprudence concerning air travel is significantly more nuanced, and often more confusing."

The CRS said courts "have struggled to determine when an overhead flight constitutes a government taking [or appropriation] under the Fifth and 14th Amendments. With the ability to house surveillance sensors such as high-powered cameras and thermal-imaging devices, some argue that drone surveillance poses a significant threat to the privacy of American citizens. Because the Fourth Amendment's prohibition against unreasonable searches and seizures applies only to acts by government officials, surveillance by private actors such as the paparazzi, a commercial enterprise or one's neighbor is instead regulated, if at all, by state and federal statutes and judicial decisions.

"Yet, however strong this interest in privacy may be," the report said, "there are instances where the public's First Amendment rights to gather and receive news might outweigh an individual's interest in being let alone."

The report said: "Additionally, there are a host of related legal issues that may arise with this introduction of drones in U.S. skies. These include whether a property owner may protect his property from a trespassing drone; how stalking, harassment and other criminal laws should be applied to acts committed with the use of drones; and to what extent federal aviation law could pre-empt future state law.

"Because drone use will occur largely in federal airspace, Congress has the authority or can permit various federal agencies to set federal policy on drone use in American skies," the report said. "This may include the appropriate level of individual privacy protection, the balancing of property interests with the economic needs of private entities, and the appropriate safety standards required."

The report concluded: "The legal issues discussed in this report will likely remain unresolved until the civilian use of drones becomes more widespread. To that end, the FAA has been tasked with developing 'a comprehensive plan to safely accelerate the integration' of drones into the national airspace, which focuses on the safety of the drone technology and operator certification."

The deadline for the development of a plan has passed, the report said, but the FAA has until the end of fiscal 2015 to implement such a plan.

"Additionally, the FAA must identify six test ranges where it will integrate drones into the national airspace. This deadline, 180 days after enactment of the act, has also elapsed without FAA compliance. Once these regulations are tested and promulgated, the unique legal challenges that could arise based on the operational differences between drones and already ubiquitous fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters may come into sharper focus."

The U.S. Supreme Court, of course, has ruled a number of times on intrusive searches and sophisticated surveillance techniques, most notably in 2001's Kyllo vs. U.S.

In the Kyllo case, a federal government agent used a "thermal imaging device" to scan a triplex in Florence, Ore., without a warrant to determine whether marijuana was being grown. The scan showed Danny Kyllo's garage was hot compared to the rest of his home and the neighborhood, consistent with the high-intensity lamps typically used for indoor marijuana growing.

The 5-4 Supreme Court majority opinion, written by Justice Antonin Scalia, sided with Kyllo. The opinion reversed a federal appeals court, and said when the "government uses a device that is not in general public use, to explore details of a private home that would previously have been unknowable without physical intrusion, the surveillance is a Fourth Amendment 'search,' and is presumptively unreasonable without a warrant."