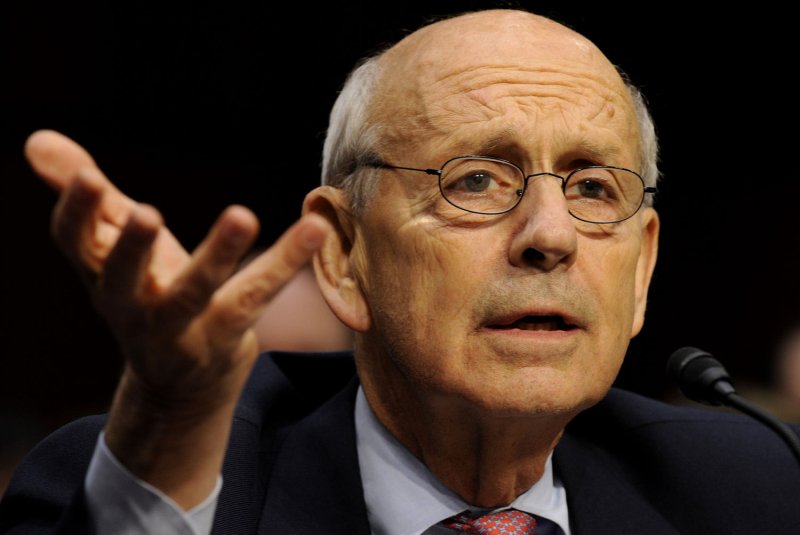

Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer in 2011 -- UPI/Roger L. Wollenberg |

License Photo

WASHINGTON, April 8 (UPI) -- New list of emergency items for your car: first-aid kit, flares, tools, clean underwear -- for those inevitable strip searches at the jail after routine traffic stops. The concept gives new meaning to the usual police order, "Spread 'em."

Last week, a narrow majority of the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that jail strip searches for most prisoners are compatible with the Constitution, no matter how insignificant the offense, no matter that there's no indication of weapons or contraband and despite the Fourth Amendment's ban on "unreasonable searches."

Writing for the 5-4 majority, Justice Anthony Kennedy pointed out that Supreme Court precedent says, "A regulation impinging on an inmate's constitutional rights must be upheld 'if it is reasonably related to legitimate penological interests,'" and a court majority has "upheld a rule requiring pretrial detainees in federal correctional facilities 'to expose their body cavities for visual inspection as a part of a strip search conducted after every contact visit with a person from outside the institution[s]," deferring to the judgment of correctional officials that the inspections served not only to discover but also to deter the smuggling of weapons, drugs and other prohibited items."

Kennedy said: "Correctional officials have a legitimate interest, indeed a responsibility, to ensure that jails are not made less secure by reason of what new detainees may carry in on their bodies. Facility personnel, other inmates and the new detainee himself or herself may be in danger if these threats are introduced into the jail population. ...

"In addressing this type of constitutional claim," Kennedy said, "courts must defer to the judgment of correctional officials unless the record contains substantial evidence showing their policies are an unnecessary or unjustified response to problems of jail security. That necessary showing has not been made in this case."

Two court members who joined in the majority, Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito, insisted in concurring but separate opinions that exceptions would have to be made to the general rule of all prisoners stripping down.

"The court is nonetheless wise to leave open the possibility of exceptions, to ensure that we 'not embarrass the future,'" the chief justice said.

Roberts and Alito said strip searches are reasonable only if a prisoner is about to be admitted to the general population of a jail.

Also, Alito said, the court majority "does not address whether it is always reasonable, without regard to the offense or the reason for detention, to strip search an arrestee before the arrestee's detention has been reviewed by a judicial officer. The lead opinion [by Kennedy] explicitly reserves judgment on that question. ... In light of that limitation, I join the opinion of the court in full."

The four dissenters, led by Justice Stephen Breyer, had even more reservations than Alito. Breyer was not shy about addressing them in his separate dissenting opinion, which the other three liberals joined.

"The kind of strip search in question involves more than undressing and taking a shower (even if guards monitor the shower area for threatened disorder)," Breyer said. "Rather, the searches here involve close observation of the private areas of a person's body and for that reason constitute a far more serious invasion of that person's privacy."

Breyer said in his view, "such a search of an individual arrested for a minor offense that does not involve drugs or violence -- say a traffic offense, a regulatory offense, an essentially civil matter, or any other such misdemeanor -- is an 'unreasonable searc[h]' forbidden by the Fourth Amendment, unless prison authorities have reasonable suspicion to believe that the individual possesses drugs or other contraband. And I dissent from the court's contrary determination."

Seemingly at a loss for words, Breyer borrowed language from the lower appeals courts, which "more directly described the privacy interests at stake, writing, for example, that practices similar to those at issue here are 'demeaning, dehumanizing, undignified, humiliating, terrifying, unpleasant, embarrassing, [and] repulsive, signifying degradation and submission.'"

The case that brought last week's ruling involved Albert Florence.

In 1998, Florence was arrested after fleeing from police officers in Essex County, N.J. He was charged with obstruction of justice and use of a deadly weapon. Florence pleaded guilty to two lesser offenses and was sentenced to pay a fine in monthly installments.

But in 2003, after he fell behind on payments and failed to appear at an enforcement hearing, a bench warrant was issued for his arrest. Though he paid the outstanding balance less than a week later, "for some unexplained reason, the warrant remained in a statewide computer database," Kennedy said in his majority opinion. Two years later in Burlington County, N,J., Florence and his wife were stopped in their car by a state trooper.

The trooper arrested Florence based on the incorrect information in the database. Florence was held in the Burlington County Detention Center for six days, then was transferred to the Essex County Correctional Facility.

While at the first jail, Florence said he "had to open his mouth, lift his tongue, hold out his arms, turn around and lift his genitals." At the second detention center, Florence, "like other arriving detainees, had to remove his clothing while an officer looked for body markings, wounds, and contraband; had an officer look at his ears, nose, mouth, hair, scalp, fingers, hands, armpits, and other body openings; had a mandatory shower; and had his clothes examined. [Florence] claims that he was also required to lift his genitals, turn around, and cough while squatting."

After officials finally discovered that the bench warrant was a mistake, Florence was freed. He filed suit alleging constitutional violations, saying there should not have been such an invasive search unless officials suspected he had weapons or other contraband. A U.S. appeals court eventually ruled against him, and the Supreme Court majority agreed.

Reaction to last week's ruling was predictable.

"Today's decision jeopardizes the privacy rights of millions of people who are arrested each year and brought to jail, often for minor offenses," Steven R. Shapiro, legal director of the ACLU, said in a statement. "Being forced to strip naked is a humiliating experience that no one should have to endure absent reasonable suspicion. Jail security is important, but it does not require routinely strip searching everyone who is arrested for any reason, including traffic violations, and who may be in jail for only a few hours. "

But he conceded, "The practical impact of the decision remains to be seen. Ten states prohibit strip searching minor offenders as a matter of state law, and those laws are unaffected by today's opinion. In addition, the [Supreme] Court was careful to recognize that strip searches may still be unconstitutional under certain circumstances." International law also limits strip searches.

"The best way to preserve the privacy of the millions of Americans who are arrested each year for minor offenses," Shapiro added, "is not to put them in jail in the first place. Instead, we should be using cheaper and more effective alternatives to incarceration."

About 13 million people are committed each year to the nation's jails.

Local county sheriffs saw the positive side.

Genesee County, Mich., Sheriff Robert Pickell told mlive.com the Supreme Court ruling was "appropriate" given the nature of the circumstances in many county jails, and strip searches should be left to the discretion of jail officials. But they shouldn't be mandatory.

"What we have to be careful of is we don't abuse the strip search," he told mlive.com. "When law enforcement starts to abuse it, and the abuse becomes great, then we force the courts to restrict us."

"I think here the Supreme Court is saying it's appropriate for us to do it, but we don't have to," he said.

Pickell said a strip search is different than a body cavity search, which he said can only be done in his state with reasonable suspicion of contraband and requires a doctor's presence.

Lee County, Miss., Sheriff Jim Johnson told WVTA.com, "I know here in the nine years that I've been sheriff we've had several lawsuits that have been filed based strictly on strip searching."

His deputies were required by law to justify a strip search and show why a prisoner needed one. Now he has more leeway.

"We've had [incoming prisoners] hide razor blades," Johnson told WVTA. "We've had them hide narcotics. We've had them hide money. We've had them hide weapons. It is amazing what we have been able to get here just under the limited strip search that we had."

Hanging on the wall at the Lee County Adult Detention Center is a picture of a jailer killed on the job. Casey Harmon was shot in the jail by a prisoner arrested on a misdemeanor charge, WVTA said.

The incoming prisoner "did not show any [hostile] actions," Johnson said. "The charge did not warrant a strip search. Yet he had a pistol hid that would've been found if we would have strip searched him."