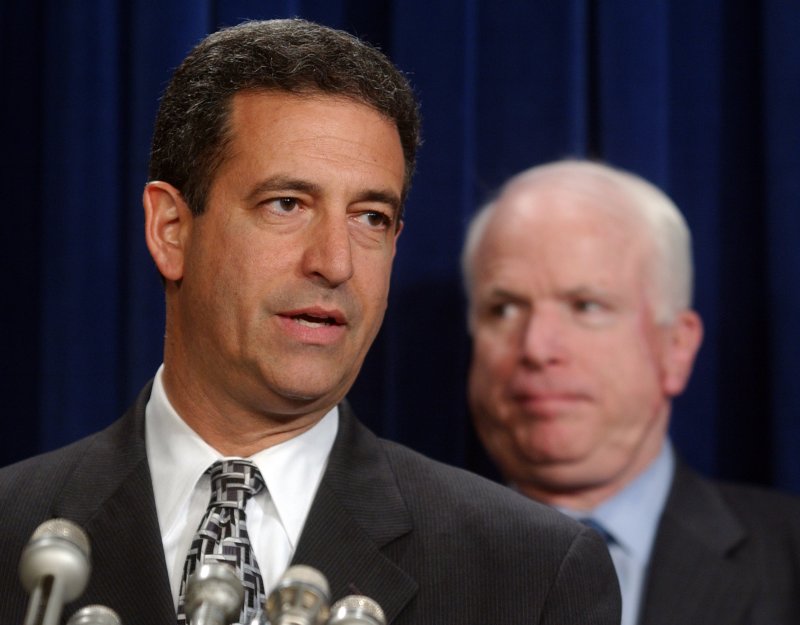

Sen. Russell Feingold speaks to members of the press at a news conference to introduce legislation on campaign 527 reforms, on September 22, 2004 in Washington. Sen. John McCain, R-AZ, looks on...(UPI Photo/Michael Kleinfeld) |

License Photo

WASHINGTON, Nov. 13 (UPI) -- The Securities and Exchange Commission is being flooded with support for a proposed regulation that would undo at least some of the effects of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Citizens United vs. Federal Election Commission -- which opened the floodgates to often secret corporate political contributions that threaten to swamp American elections.

The proposed SEC regulation requested by a committee of professors on corporate law would require "public companies to disclose to shareholders the use of corporate resources for political activities."

In other words, even if corporate executives now earmarking company money for political candidates and parties would not have to reveal the recipients to the public or the media, they would have to disclose the amounts and recipients to stockholders.

The SEC has been considering the rule since it was proposed in August.

First a little history.

The 2002 Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act, popularly known as McCain-Feingold, prohibited corporations and unions from using their general treasury funds to make independent expenditures for an "electioneering communication" or for speech that expressly advocates the election or defeat of a candidate.

Corporations could still express their political views by setting up a political action committee, but PACs are subject to even more restrictions and disclosures. PAC money has to come from the pockets of corporate executives, not from the corporate treasury, and amounts are severely restricted to $2,500 in every election cycle.

The 5-4 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in 2010 in Citizens United swept away much of that.

Writing for the narrow majority, Justice Anthony Kennedy said the political speech of corporations was protected by the First Amendment and could not be restricted by McCain-Feingold, and that applied even if the funds corporations were spending on political races belonged to stockholders.

PACs "are burdensome alternatives" that must keep detailed records and make reports to the FEC, Kennedy said.

In a little discussed side issue, eight of the nine justices agreed Congress, if it wanted to, could force corporations to make donations public.

The changes to the political landscape from the ruling were so sweeping that President Barack Obama, alarmed that Democrats would come up with the short end of the stick on corporate money, publicly scolded the justices during his State of the Union address that month.

The effect of the January Supreme Court decision was immediate on that year's midterm elections in November, the most expensive in U.S. history.

Common Cause said 2010 numbers compiled by the Center for Responsive Politics show "$293 million came from groups operating independently of the candidates or political parties. Those groups, known as 'super PACs,' '527 organizations' and '501(c) organizations,' were free to spend without limits and accept unlimited donations from corporations, trade associations and unions."

A little less than half of that independent money, $138 million, came from 501(c) groups -- named for a section of federal law -- that are not required to report donors to the FEC.

The Citizens United ruling led 10 law professors to form the "Committee on Disclosure of Corporate Political Spending." In August, the group submitted a "petition for rulemaking" to the Securities and Exchange Commission: "We ask that the commission develop rules to require public companies to disclose to shareholders the use of corporate resources for political activities."

In other words, if executives want to participate in politics using corporate funds, they would have to publicly tell stockholders what they're doing. Of course, the odds of stockholders passing that information on to the media are pretty good.

The committee is composed of "10 academics [from Harvard, Columbia, Yale and similar institutions] whose teaching and research focus on corporate and securities law."

"Disclosure of corporate political spending is necessary not only because shareholders are interested in receiving such information, but also because such information is necessary for corporate accountability and oversight mechanisms to work," the petition argued.

"Absent disclosure, shareholders are unable to hold directors and executives accountable when they spend corporate funds on politics in a way that departs from shareholder interests."

The petition said "a substantial amount of the public-company resources spent on politics are currently not disclosed in any public filing and thus would be hidden even from someone who invested significant effort in trying to put together all the publicly available information about a company's public spending. ... [A] substantial amount of corporate spending on politics is conducted through intermediaries not required to disclose the sources of their contributions to the public."

If the SEC decides to act on the petition it must file notice in the Federal Register of the time and place of the rulemaking procedure. But the SEC is under no deadline to act on the petition.

In the meantime, the commission is being inundated with public comment supporting the law professors' request.

Typical are comments from Susan R. Holmberg, who holds a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and is the program director at the Center for Popular Economics, "an organization that teaches economics literacy to the general public."

In what is essentially an academic study, Holmberg says: "The benefits of [corporate political activity] disclosure would be substantial. This rule would help to correct the market failures that currently exist in [corporate political activity] by creating incentives for managers to focus less on their personal gains and more on maximizing shareholder wealth ... In other words, requiring corporations to disclose their political donations would substantially improve the efficiency of capital markets, which is why I urge the SEC to promulgate a rule requiring corporate political disclosure for publicly traded companies."

Also typical was a comment from Glenn Davis, representing "the Council of Institutional Investors, a non-profit association of public, union and corporate pension funds with combined assets in excess of $3 trillion."

"The council is not in principle opposed to corporate political spending provided it is transparent -- both in terms of the amount spent and the process for board oversight of such spending. Any future rulemaking would ideally address both of these areas," Davis said.

Ted Wheeler, Oregon's state treasurer, told the SEC: "I respectfully request the Securities and Exchange Commission consider proposing a rule to require public companies to disclose campaign spending. This request is a direct result of the rapidly increasing frequency with which Oregon encounters this issue. The SEC is the right body to establish a uniform set of guidelines to facilitate company compliance with the requirement, and to enhance shareholders' ability to gather and analyze this information.

"Again, this is not an argument to limit political speech," Wheeler said. "This is about openness, transparency and about providing accountability for shareholders. At the end of the day, that is good business and it will be good for Oregonians."

A group of more than 30 "progressive" firms filed a joint comment offering "strong support" for the professors' petition, saying in part: "Corporations use treasury funds for a variety of political purposes, including direct contributions to state-level political candidates, including judges, to fund ballot initiatives, political parties and a range of tax-exempt entities, such as trade associations and 527 organizations" -- groups named after a section of the U.S. code that must report donations -- "that engage in political activity."

Also typical was comment by Christianna Wood of the Board of Governors and George Dallas, chairman of the Business Ethics Committee, of the International Corporate Governance Network.

The network "is a not-for-profit body, founded in 1995, which has evolved into a global membership organization of over 500 leaders in corporate governance in 50 countries, with institutional investors representing assets under management of around U.S. $18 trillion."

The network "recognizes that corporate political activity can be positive. However, when corporate resources are deployed to seek political influence there is also potential for abuse. In the extreme this can lead to serious breaches of business ethics, particularly when influence is sought through corrupt practices or in ways that are not consistent with promoting the long-term interests of the company and its investors," they said.

"Given these concerns we believe that disclosure of corporate political spending is only a basic first step to ensure transparency and accountability of corporations to their investors."

Less typical was comment from Keith Paul, a lawyer in Irvine, Calif., and an adjunct professor of law at Chapman University Law School.

Paul also is a former state commissioner of corporations "and in that capacity administered and enforced California's securities laws," he said. "I have also served as co-chairman of the Corporations Committee of the Business Law Section of the California State Bar and chairman of the Business and Corporate Law Section of the Orange County Bar Association. I am writing in my individual capacity and not on behalf of my law firm, the law school or any of my law firm's clients."

Paul argued the adoption of the proposed rule would be a forced subsidy by the majority of shareholders.

"The costs of the ... proposal will be borne by 100 percent of the shareholders even though petitioners have acknowledged that when put to a vote, less than one-third of the shareholders on average support political spending proposals. Accordingly, petitioners are in effect asking the two-thirds to subsidize the interest of the minority. Petitioners have provided no justification for this wealth transfer from the majority to the minority."

Moreover, he said the professors "note that since 2004 'large public companies have increasingly agreed voluntarily to adopt policies requiring disclosure of the company's [sic] spending on politics.' In addition, they provide data that demonstrate that the number of shareholder proposals with respect to political spending has increased. Rather than support the need for additional mandatory disclosure, the [professors'] evidence actually demonstrates the lack of any need for government intervention."