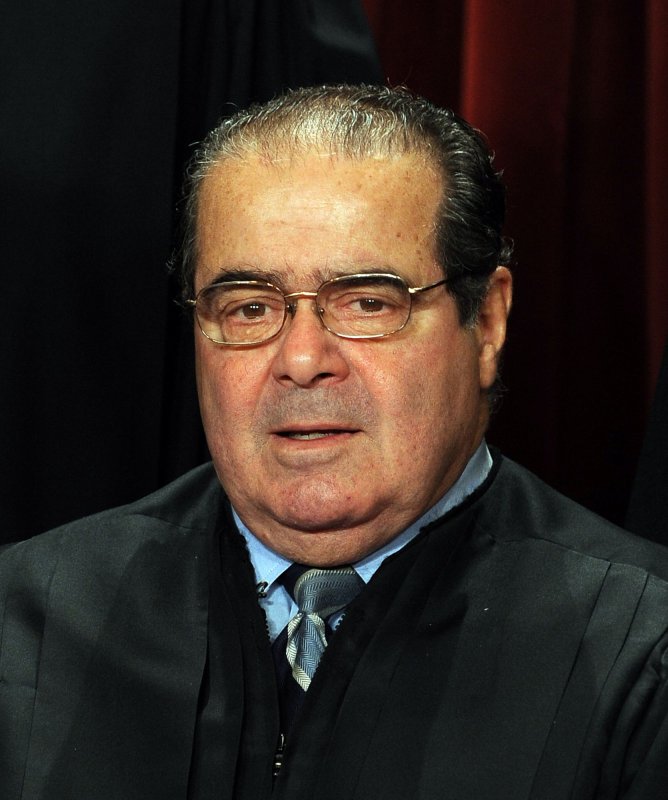

Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, pictured Oct. 8, 2010. UPI/Roger L. Wollenberg |

License Photo

WASHINGTON, Sept. 25 (UPI) -- Many legal analysts say we are hearing the death rattle of the class action lawsuit, pushed into last sacrament territory by a 5-4 conservative majority on the U.S. Supreme Court that has enormous sympathy for business but almost none at all for the average consumer.

For the public, the main blow came from the ruling in Walmart vs. Dukes in June, when the high court shattered the largest class action in U.S. history. But legal scholars see the high court's 5-4 ruling in AT&T Mobility vs. Concepcion as far more inimical to the class action concept.

First, the Walmart details.

The Supreme Court unanimously agreed the massive class action sexual discrimination suit against retail giant Walmart could not stand.

But the court's four-member liberal bloc, in a partial dissent, said the putative 1.5 million women in the class should have been given a chance to show there was enough "commonality" in their situations to qualify as a class.

The case started in San Francisco in 2001 when six women filed suit claiming Walmart discrimination, in part because they were passed over for promotion in favor of men.

Walmart had complained the "nationwide class includes every woman employed for any period of time over the past decade, in any of Walmart's approximately 3,400 separately managed stores, 41 regions and 400 districts, and who held positions in any of approximately 53 departments and 170 different job classifications. The millions of class members collectively seek billions of dollars in monetary relief under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, claiming tens of thousands of Walmart managers inflicted monetary injury on each and every individual class member in the same manner by intentionally discriminating against them because of their sex, in violation of the company's express anti-discrimination policy."

A federal appeals court panel and the full 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, both divided, approved the certification of the class.

But the majority opinion written by Justice Clarence Thomas seemed to suggest such claims could only been handled individually. The opinion said when plaintiffs seek individual relief such as back pay or reinstatement, the company has "the right to raise any individual affirmative defenses it may have, and to 'demonstrate that the individual applicant was denied an employment opportunity for lawful reasons.'"

Thomas' opinion said the appeals court tried to replace this procedure with a "trial by formula," using a "sample set," with the result applied to the huge class. "We disapprove that novel project."

The issue in April's AT&T Mobility was somewhat different.

In California, Vincent and Liza Concepcion took advantage of an AT&T offer of free cellphones under their service contract -- then noticed they were being charged a sales tax on the "free" cellphones.

The cellphone contract provided for arbitration of all disputes, but did not permit class arbitration.

The Concepcions sued the company in federal court. Their suit was consolidated with a class action that claimed AT&T had engaged in false advertising by charging sales tax on "free" phones. A federal judge and appeals court rejected AT&T's request to compel arbitration under the contract.

But the Supreme Court eventually ruled 5-4 that the Federal Arbitration Act pre-empted California case law allowing such suits. The FAA makes arbitration agreements "valid, irrevocable, and enforceable, save upon such grounds as exist at law or in equity for the revocation of any contract."

The narrow majority's opinion, written by Justice Antonin Scalia, said the state's 2005 "Discover Bank" rule "stands as an obstacle to the accomplishment and execution of the full purposes and objectives of Congress," and therefore was trumped by the FAA.

The Concepcions, and everyone else, would have to go back to individual arbitration to get the $30.22 in sales tax.

Writing for the four-member liberal bloc, Justice Stephen Breyer asked, "What rational lawyer would have signed on to represent the Concepcions in litigation for the possibility of fees stemming from a $30.22 claim?" Citing an appeals court opinion, Breyer said, "The realistic alternative to a class action is not 17 million individual suits, but zero individual suits, as only a lunatic or a fanatic sues for $30."

"So what?" you may ask.

What if most or all consumer transactions became subject to arbitration contracts?

Ashby Jones, writing in The Wall Street Journal blog, cites Vanderbilt Law Professor Brian Fitzpatrick.

"If the court goes down AT&T's path, the consequences could be staggering," Fitzpatrick said last year. "It could be the end of class action litigation. ... [V]irtually all class actions today occur between parties who are in transactional relationships with one another: shareholders and corporations, consumers and merchants, employees and employers. Because they are in transactional relationships, they are able to enter arbitration agreements with class action waivers.

"Once given the green light," Fitzpatrick warned, "it is hard to imagine any company would not want its shareholders, consumers and employees to agree to such provisions."

In a piece posted on SCOTUSBLOG.com, David S. Schwartz, professor of Law at the University of Wisconsin Law School, conceded, "Walmart vs. Dukes caused much consternation for placing significant limits on class actions. ... [But] AT&T Mobility vs. Concepcion ... goes much farther than Walmart. It entirely kills most class actions."

Schwartz said the AT&T case was the latest "in a long line of Supreme Court decisions interpreting the Federal Arbitration Act in a manner consistently hostile to consumer and employee protection laws. An obscure backwater of contract law, FAA jurisprudence flies under the radar of most policymakers and legal sophisticates, and its low profile is compounded by the obscurity of language and reasoning in the Supreme Court's decisions in the area."

The AT&T high court ruling "appears to hold that a party to an arbitration agreement cannot be sued in a class action."

Schwartz said the AT&T case, which he called Concepcion, was the one to watch out for.

"Without minimizing, Walmart vs. Dukes, getting upset about that case is like flipping out over a brief thundershower a few weeks after having slept through Hurricane Irene," he said. "The implications of Concepcion are staggering. Most class actions arise out of contractual relationships. Consumer, employment discrimination, wage and hour and securities class actions all arise out of transactions that begin with a contract. Any and all potential defendants of such claims can immunize themselves from class actions by the simple expedient of adding an arbitration agreement to their contracts. Since these are almost always adhesion contracts, all that's required is word-processing -- certainly not bargaining."

Writing in the ABA Journal under the headline "The End of Consumer Class Actions?" Debra Cassens Weiss said, "The U.S. Supreme Court has sided with AT&T in its bid to enforce contract provisions banning class actions and requiring individual arbitration in consumer disputes."

Allessandro Presti, writing in the Columbia Business Law Review, also cites Fitzpatrick.

Writing in The San Francisco Chronicle, Fitzpatrick points out, "virtually all class actions today occur between parties who are in transactional relationships with one another: shareholders and corporations, consumers and merchants, employees and employers. ... Sometimes businesses inflict injuries too small to sue over. How many people will sue when someone cheats them out of $100? How many lawyers will take a case worth $1,000? Not many. But, if people don't sue, businesses know they can cheat people out of small amounts with impunity."

But Presti, for now, refuses to join the class action mourners, saying those predicting its death "may be jumping the gun."

Presti said it's unclear how much the Concepcion ruling will affect consumer and other class action litigation. Many realistic attempts to remedy corporate injury do not involve class action.

And there's always the chance Congress could act legislatively to limit the impact of the ruling, though that seems less likely with the major parties dividing up the Congress.

Finally, Presti said, "the heavily overlapping nature of regulatory authority in the United States means that government agencies could use rulemaking, litigation or other regulatory measures to curtail the impact of Concepcion. For instance, many consumer class actions, including the Concepcions', were brought under laws prohibiting false or deceptive advertising, which the [Federal Trade Commission's] Bureau of Consumer Protection has authority to enforce."

Presti said Fitzpatrick notes the Securities and Exchange Commission "has frowned upon arbitration, and could use its authority to prevent Concepcion from reaching shareholder class actions. ... Some have suggested that the newly created Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection may use its rulemaking authority to prohibit class action bans for consumer financial products."

What Presti doesn't say is what would happen to class action if some future administration or congressional majority hostile to government regulation pulls hard on the regulatory reins, or even drums most regulation out of the law.