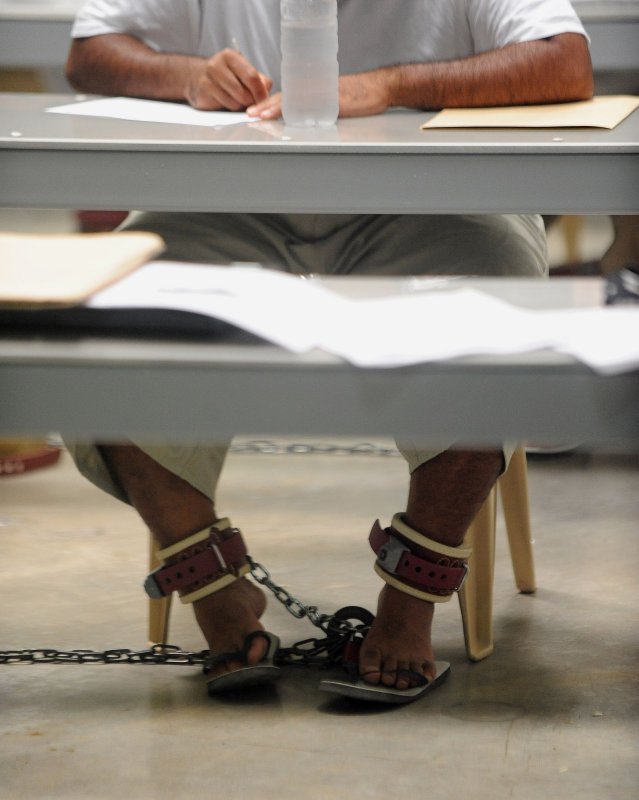

Detainees attend a class at Camp VI in Camp Delta at Naval Station Guantanamo Bay in Cuba on July 8, 2010. Detainees are shackled to the floor when contractors are teaching classes to insure teachers' safety. UPI/Roger L. Wollenberg |

License Photo

WASHINGTON, May 29 (UPI) -- Just how powerful is the president of the United States -- does he or she have the power to stick a foreign national into Guantanamo and throw away the key, when that foreign national insists he's never carried arms against the United States?

Even if that power flies in the face of international law?

What about the foreign national who has never carried a weapon but has been a member of a terror group such as al-Qaida?

President George W. Bush claimed the authority to indefinitely detain "enemy combatants," those illegally carrying out attacks on this country, people who are not protected as prisoners of war under the Geneva Conventions. President Barack Obama claims essentially the same authority, though he has abandoned the phrase "enemy combatant."

Both presidential claims are rooted in the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force enacted by Congress.

The AUMF in part says the president "is authorized to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on Sept. 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons, in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations or persons."

Now the U.S. Supreme Court is being asked to determine whether "the laws of armed conflict" -- international law -- "determine the scope of who may be indefinitely detained under the Authorization for Use of Military Force."

The justices all this term have been swatting away petitions from prisoners at the U.S. Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, detention center by the handful. But one petition, filed by lawyers for Toffiq Nasser Awad al-Bihani, internment serial number 893, survives. In fact, the U.S. Justice Department has been asked to respond to his petition by June 10.

Al-Bihani uses what could be called the "Don't shoot me. I'm only the piano player" defense: At worst he was a cook who never carried a weapon, he argues, a civilian who wasn't part of the fighting force.

All Guantanamo cases are routed through the U.S. court of appeals in Washington, where the appeals court ruled in a precedent-setting case involving al-Bihani's brother -- who was part of a military brigade and carried an assault rifle -- that relying on the international laws of war to determine the scope of the president's detention power is "both inapposite and inadvisable."

Al-Bihani's petition asks the Supreme Court to reverse that precedent and to rule that international law does apply to detentions.

It also seeks to create a "bright line" -- a clear line of demarcation -- between those who engaged in combat and those who just served the goat stew in training camp. But the petition makes no mention of U.S. law that makes it a serious crime merely to act in support of terror organizations.

"The (appeals court's) standard allows indefinite detention of an individual based solely on his being 'part of' a group, al-Qaida, without regard to whether the individual in question ever personally engaged in hostilities (direct or otherwise) against the United States or any coalition partner" in Afghanistan, al-Bihani's petition argues.

"While the executive claims to be acting under congressional authorization in allowing such detention, the proffered basis for that authority, the AUMF, does not support the executive's position," the petition said. "Rather, the executive can legitimately justify detention only by reference to the laws of armed conflict -- laws it at once embraces and shuns. Contrary to its own guidance in other areas and contrary to its own public proclamations, the executive has promulgated guidance that purports to justify the indefinite detention of civilians at Guantanamo based solely on their associations and not based on their deeds. This is unsupportable under the laws of armed conflict."

Al-Bihani was a cook for the Taliban when he was captured in Afghanistan, some sources say. His petition says he was captured in Iran before being turned over to U.S. custody.

A federal judge upheld al-Bihani's "indefinite detention based solely on the finding that he was part of al-Qaida." Al-Bihani "admits he was part of al-Qaida while training in Afghanistan. ... He denies remaining part of al-Qaida after that training but the (judge) found to the contrary and (al-Bihani) does not challenge that factual finding."

The judge did not find that al-Bihani engaged in hostile action.

The federal appeals court then ruled to summarily affirm the judge's verdict.

But the appeals court ruled wrongly, al-Bihani's petition argues.

"Under the principles of the laws of armed conflict embodied in both United States and 'international' sources, (al-Bihani) is a civilian because he has not given up the protections of that status by direct and active participation in hostilities," his petition argues.

After citing a number of U.S. policy and military treatises, the petition cites 1949's Geneva Convention III, "Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War," prohibiting attacks on civilians "taking no part in hostilities." It also cites the convention's 1949 Protocol II, which says civilians "shall not be the object of attack ... unless and for such time as they take a direct part in hostilities."

Despite the president's "claim of detention authority over" al-Bihani, the Obama administration "has recently acknowledged that Protocol II represents United States military practice and requested the Senate to ratify it," the petition said.

"In other words, even though he was a 'part of' al-Qaida, because (al-Bihani) did not take part in hostilities under Additional Protocol II -- a provision the executive concedes is the law of the land -- he cannot be targeted or detained under the laws of armed conflict," the petition said.

"The consequences of that determination are important: 'Combatants' may be deliberately targeted with deadly military force; civilians not participating in hostilities may not. Combatants may also be detained in order to prevent their return to the battlefield. The same is not true of civilians."

"Because of the (appeals court's) erroneous refusal to apply the laws of armed conflict to the executive's broad claims of indefinite-detention authority, (al-Bihani) faces the very real prospect of spending the remainder of his life in military detention -- a civilian detained as a combatant in a never-ending war in which he did not fight."