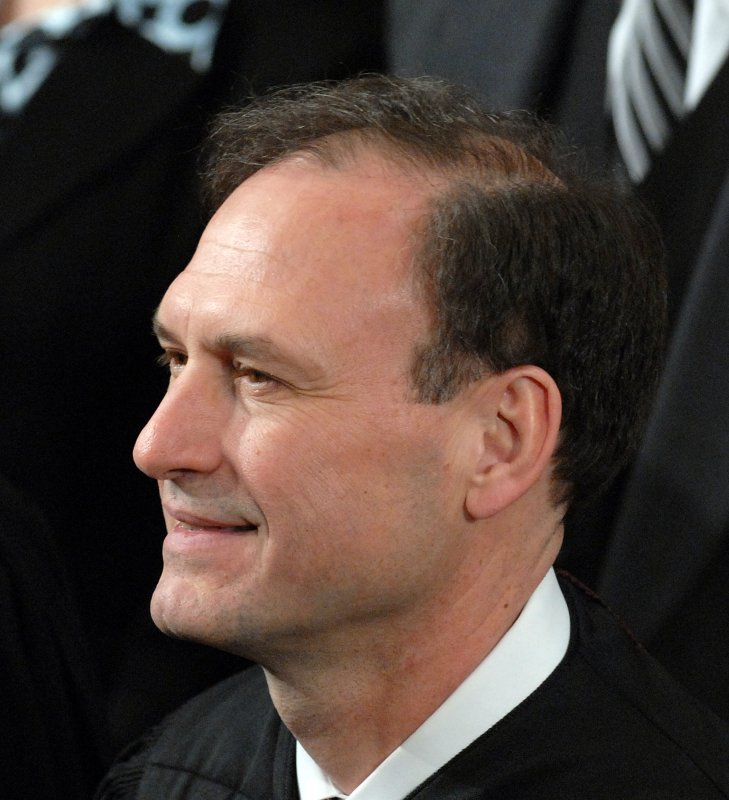

Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito arrives to listen to U.S. President George W. Bush deliver his State of the Union address in the House of Representatives Chamber of the U.S. Capitol in Washington on January 23, 2007. (UPI Photo/Roger L. Wollenberg) |

License Photo

WASHINGTON, Aug. 22 (UPI) -- Affirmative action has helped millions of minorities get a leg up and outraged millions of whites who feel they were treated unfairly, but the policy as a matter of law may be living on borrowed time: At the U.S. Supreme Court, it comes down to the math.

Affirmative action is in the stream of American life, whether the average person is aware of it or not. The federal government and local municipal agencies rely heavily on affirmative action -- taking into account someone's race -- in hiring and promotion.

A big bump in the affirmative action road came in June 2009 when the high court voted 5-4 along its ideological divide that federal civil rights law can be used to ban discrimination against whites. The case was brought by 20 white firefighters in New Haven, Conn. -- including one white Hispanic -- whose passing scores on a promotion test were thrown out because no blacks had scores high enough to be promoted.

The 2003 exam was designed to select 15 candidates for captain and lieutenant. When no blacks and only one Hispanic scored a passing grade, the city decided not to use the results for promotions, saying it did not want exposure to suits from blacks and Hispanics.

The white firefighters filed suit, citing the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which bans discrimination on the basis of race or sex. A federal judge and a federal appeals court ruled for the city. The U.S. Supreme Court said fear of litigation was not enough for the city to throw out the results of the test.

Writing for the majority, Justice Anthony Kennedy said, "The problem, of course, is that after the tests were completed, the raw racial results became the predominant rationale for the city's refusal to certify the results. The injury arises in part from the high, and justified, expectations of the candidates who had participated in the testing process on the terms the city had established for the promotional process."

Kennedy said: "Many of the candidates had studied for months, at considerable personal and financial expense, and thus the injury caused by the city's reliance on raw racial statistics at the end of the process was all the more severe. Confronted with arguments both for and against certifying the test results -- and threats of a lawsuit either way -- the city was required to make a difficult inquiry. But its hearings produced no strong evidence of a disparate-impact violation (a violation of the rights of minorities), and the city was not entitled to disregard the tests based solely on the racial disparity in the results."

The states are beginning to kick back at affirmative action requirements. Michigan, California, Nebraska and Washington state voters have enacted amendments banning the use of race for advantage in the public sector, including college admissions.

Now the undergraduate admissions policy of the University of Texas is under legal attack.

More than three-fourths of freshmen enroll at the Austin school under a state law that gives automatic admission to students in the top 10 percent of their high school classes, the Austin American-Statesman reported. For the remainder, the school considers a number of factors, including race.

Two white students denied UT admission under the policy challenged it in federal court.

The American-Statesman said the school won at the trial court level last year, with U.S. District Judge Sam Sparks in Austin saying the admissions policy avoids quotas and other pitfalls outlined in a 2003 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Grutter vs. Bollinger that upheld affirmative action at the University of Michigan Law School.

The challenge is now before a panel of the 5th U.S. Court of Appeals, one of the most conservative circuits of the 13 in the country; the three-judge panel has heard argument, and should rule within the next couple of months, though they gave no signal of which way they would jump, the newspaper said.

One of the three jurists on the panel, U.S. Appellate Judge Patrick Higginbotham, indicated he thought the UT policy was crafted to survive a Grutter analysis, asking "Where's the flaw?"

But the question may not be whether the Texas case would survive Grutter, but whether Grutter itself would survive.

The 2003 case at the time was recognized as the savior of affirmative action, which was under intense political pressure from the right.

In Grutter, a 5-4 majority said the law school's "narrowly tailored use of race in admissions decisions to further a compelling interest in obtaining the educational benefits that flow from a diverse student body is not prohibited by the equal protection clause" of the 14th Amendment or U.S. civil rights law.

Writing for the majority, Justice Sandra Day O'Connor said to "be narrowly tailored, a race-conscious admissions program cannot" insulate minority students from competition with all other applicants. But a race-conscious admissions program must be flexible enough to consider all the elements of diversity in light of the qualifications of each applicant.

"It follows that universities cannot establish quotas for members of certain racial or ethnic groups or put them on separate admissions tracks," she said.

O'Connor suggested affirmative action should be phased out, possibly over the next 25 years.

Writing the main dissent, Chief Justice William said he agreed if a race-conscious program were to survive, it must be narrowly tailored.

"I do not believe, however, that the University of Michigan Law School's means are narrowly tailored to the interest it asserts," he said. "The law school claims it must take the steps it does to achieve a 'critical mass' of underrepresented minority students. ... But its actual program bears no relation to this asserted goal. Stripped of its 'critical mass' veil, the law school's program is revealed as a naked effort to achieve racial balancing."

Rehnquist was joined by Kennedy and Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas.

Kennedy wrote separately in dissent. "The law school has the burden of proving, in conformance with the standard of strict scrutiny, that it did not utilize race in an unconstitutional way. ... At the very least, the constancy of admitted minority students and the close correlation between the racial breakdown of admitted minorities and the composition of the applicant pool, discussed by the chief justice ... require the law school either to produce a convincing explanation or to show it has taken adequate steps to ensure individual assessment. The law school does neither."

Shoot forward to 2010. The Grutter court has changed considerably.

O'Connor, of course, is gone, retiring in 2006. To make up the Grutter five-member majority, O'Connor, a moderate conservative, was joined by liberal Justices John Paul Stevens, David Souter, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer.

Souter and Stevens are retired succeeded by liberal Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

Making up the Grutter four-member minority were Rehnquist, Scalia, Thomas and Kennedy.

Rehnquist died in 2005, to be succeeded by Chief Justice John Roberts, another reliable conservative. Scalia, Thomas and Kennedy remain on the court.

But O'Connor was succeeded by Justice Samuel Alito, another hard-line conservative in the Rehnquist tradition.

That means if Grutter or a similar case comes before the Supreme Court now -- without O'Connor and with Alito -- the result would probably go 5-4 the other way, and the candle of affirmative action would be flickering very weakly indeed in the judicial wind.

Do the math.