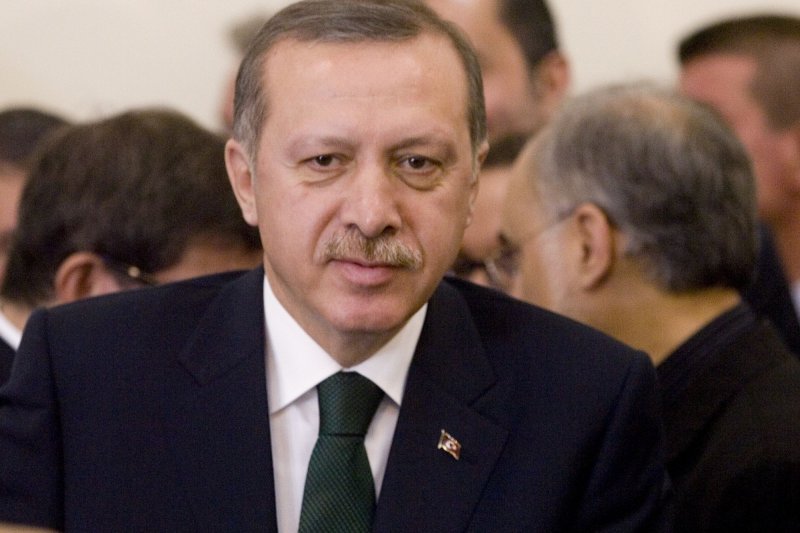

Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan is seen as Iran, Turkey and Brazil sign an agreement to ship Iran's low-enriched uranium to Turkey in exchange for fuel for a nuclear reactor in Tehran, Iran, on May 17, 2010. Iran signed an agreement to swap its uranium in Turkey for enrichment, hoping to avert new international sanctions. Brazil helped broker the deal. UPI/Maryam Rahmanian |

License Photo

ISTANBUL, Turkey, April 18 (UPI) -- With its economy growing at almost 9 percent and foreign money flooding in fast, Turkey is booming, which means that Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan's ruling Justice and Development Party should cruise to re-election in elections this June.

But the country is troubled by a series of profound challenges and the political divisions run deep, which helps explain the growing row with Europe and the United States over press freedom. Turkey holds the unenviable title of the most journalists arrested in the world, a total of 54, ahead of China and Iran.

In a defensive appearance before the Council of Europe's parliamentary assembly this month, Erdogan blustered that only 26 were under arrest for journalistic activities. This provoked derision but he has something of a point. The arrests, and a raid on the office of the daily Radikal to seize drafts of a book, are largely related to the murky Ergenekon affair, an alleged ultra-nationalist plot to topple the government in a military coup.

"It is a crime to use a bomb but it is also a crime to use materials from which a bomb is made. If informed that all materials needed to construct a bomb have been placed in a certain location, wouldn't the security forces collect these materials?" Erdogan declared, a roundabout way of saying that books on military coups can be explosive.

Erdogan went on to insist that the arrests were ordered by Turkey's independent judicial system, not by him. Some of those arrested have been detained for nearly four years and another cohort of military men have been arrested for another alleged plot, this one known as the "Balyoz" (Sledgehammer) coup plan. Erdogan also criticized the Turkish general staff statement that said the army "had difficulty in understanding the continued detention" of 163 military personnel as part of the investigation.

The publication of U.S. diplomatic cables by WikiLeaks has complicated matters, with U.S. diplomats complaining of Turkey's "absurd" trial and fine of Nobel Prize-winning novelist Orhan Pamuk for writing of the death of up to 1 million Armenians at Ottoman hands in 1915. This remains a deeply neuralgic issue in Turkey and the government bristled on learning that U.S. Ambassador Ross Wilson commented in a 2005 cable regarding the Pamuk issue that "it will take much work to convince the Turks that freedom should cover the right to criticize and open guarantees to protect that right."

Behind all this lies a deep division between the secular Turkish republic founded by Kemal Ataturk after the fall of the Ottoman empire in 1918 and the moderately Islamic AK Party that Erdogan leads. The army sees itself as the custodian of Ataturk's tradition but the AKP has the votes and the staunch support of most of rural Turkey and many of the new urbanites who have swollen Istanbul's population to almost 15 million.

On the surface, the tussle between the Erdogan's party and the secular and largely pro-Western Turkish elite and the military is played out over symbols like the Islamic veil for women. But the coup plots and arrests and the clampdown on the nationalist press point to the deeper fissures.

These were on display last September when Erdogan won a referendum on constitutional reform with 58 percent of the votes backing his demand to assert parliament's authority over the judiciary and the military.

Rand analyst Steve Larrabee notes that Erdogan's reforms were "strongly rejected in the country's western provinces along the Aegean and Mediterranean coast and in the middle-class districts of large cities like Istanbul and Ankara, where voters fear that socially conservative policies favored by the AKP will mean further restrictions on their Westernized lifestyles. By the same token, voters in lower-middle-class city districts and in the central and eastern Anatolian provinces supported the AKP's proposed changes in large numbers. "

Although a loyal NATO ally for 60 years, Turkey has alarmed U.S. officials by its refusal to allow U.S. troops through its territory in the Iraq war and by its increasingly hostile stance toward Israel and its warming relations with Iran. The issue of Turkey's relationship with the West is seen to pivot on the vexed issue of Turkey's application to join the European Union, where negotiations have virtually stalled.

Some key EU countries, notably Germany, France and Austria, have made no secret of their reluctance to admit a largely Islamic Turkey to their traditionally Christian club, even though Europe's sluggish economy could benefit from Turkey's markets and workforce. The Turks themselves are losing patience, with opinion polls in favor of joining the EU dropping from more than 70 percent support in 2003 to less than 40 percent today.

Erdogan says he still wants to join but Turkey is making no concessions on the continued presence of its troops in northern Cyprus, largely because the Greek Cypriots rejected the peace plan for the divided island proposed by former U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan. The result is stalemate, with the Cyprus government holding an effective veto over Turkey's dwindling EU hopes.

Erdogan's government is less popular than it was, despite the economy. So his re-election isn't a foregone conclusion, in part because of well-founded suspicions that he would use his victory as a springboard to install a presidential regime with him as president. But with a new election mandate and presiding over a strong economy fueled by the hard work of those newly prosperous and newly urbanized Anatolian Muslims that vote for him, Erdogan could claim to be the legitimate leader of a new Turkey.

The irony is that with his carefully calibrated foreign policy, balanced between the West and the Islamic world, Erdogan is re-enacting the diplomacy and the great power ambitions of the old Ottoman Empire. The capital may have moved from Istanbul to inland Ankara but the sultans would have recognized his strategy.