A new "cessation of hostilities" is beginning in Syria, with the United States and Russia preparing to coordinate airstrikes against militant jihadist factions. If the temporary cease-fire holds for the intended 10 days and fundamentally changes the conflict – and there are plenty of observers who don't expect it to – it provides a chance for the embattled government in Damascus to briefly step back from a nightmarishly complex and bloody campaign.

One of the most worrying developments in the complex Syrian war is the apparent impunity of the Assad regime, which has continued to order repeated air attacks on hospitals and other medical centers, used barrel bombs in tightly populated cities, and has even deployed chlorine as a chemical weapon. Indeed, ever since Russia entered the air war, Bashar al-Assad's government has felt increasingly secure and able to act as it wishes.

Russia's motives for helping the regime come largely from Vladimir Putin himself. He is determined to show that Russia is still a great power, especially after the contempt with which Western leaders treated it after the Soviet Union collapsed. It has proved a popular stance with most Russians, even though the military actions in Ukraine, especially Crimea, have proved costly precisely at a time of low oil and gas prices, and the sanctions imposed by the West for its behavior have been painful indeed.

Related

Such problems rarely make the Russian media, but Russians themselves are all too aware of the shortages. They also see the constant attempts by the authorities to extract taxes, tariffs and other kinds of fiscal revenue, it being commonly understood that this is necessary to "pay for Crimea."

If the Assad regime feels safe with Russia's backing, it has added assurance that Washington and other Western governments have little interest in bringing it down. For at least two years, their priority has been to crush the Islamic State, with the U.S.-led coalition at the center of an incredibly intense air war.

The long game

The sheer intensity of the aerial conflict has simply not been adequately conveyed to audiences not following it closely. In the summer of 2016, the Pentagon suggested that 45,000 IS supporters had been killed. The transparency project Airwars has tallied around 15,000 airstrikes to date, with more than 52,000 missiles and bombs dropped. The group's minimum assessment of civilian casualties is 1,592, but it believes the true figure is much higher.

And while the Russians have mounted a minority of the attacks, they have been notoriously indiscriminate – almost as bad as the Assad regime's air force – especially in the last three months of 2015.

But if the regime is now so confident and the Americans and their partners so focused on defeating IS, why is the latest cease-fire deal even happening, and what are its chances of success?

For Washington and its allies, a cessation of fighting elsewhere in Syria, which then allows it to concentrate its resources against IS, is not only acceptable but received with some enthusiasm. Russia, though, is another matter.

Putin and his government want to ensure that a friendly regime survives in Damascus, and in turn provides support for an expansion of Russian influence in the region. The Middle East so far remains largely the domain of the United States and its weak European allies; by challenging them, Putin can enjoy and grow the status he desires. Russia may be a weak state, its GDP a mere fraction of the United States' or China's, but it's not hard for Putin to portray it as a serious player on the world stage.

For Russia, a cease-fire is also a crucial means of reducing the costs of war, offering it major-player status without the costs that would usually entail. It also makes it less likely that Russia will end up sucked into a long war in the Middle East, one that might well turn out to be as big a burden as its doomed 1980s campaign in Afghanistan.

Shifting sands

Another question altogether is why Russia has now decided to participate directly in the air war against IS, rather than concentrating as it has on the militias directly engaging Assad's forces.

One likely answer is that Russia's domestic counterterrorism people are seriously worried about an increase in radicalization among its 16 million-plus Muslims, many of them thoroughly alienated from conventional society. Aiding the destruction of IS before it attracts even more adherents, especially in the Caucasus, may therefore make political sense.

So in the short term, will this latest cease-fire last? On recent evidence, not likely. Not only are IS and Jabhat Fatah al-Sham not part of it, but some other key rebel groups are deeply suspicious, even including some that have previously received Western support.

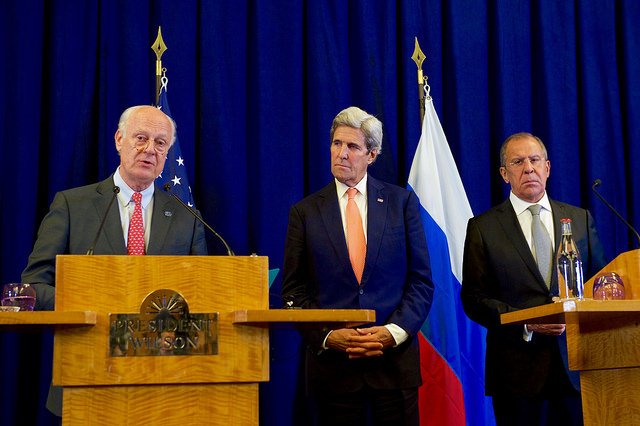

There is always hope, and at the very least, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov still have a good working relationship. But nonetheless, the best that can be hoped for is a temporary respite that allows aid to get into to the worst-affected areas, and that at least some local cease-fires might last even if the national cessation of hostilities collapses.

In the longer term, we have to recognize that this is one of the most complex conflicts that the world has seen for generations.

On both sides, it's become what amounts to a double-layered proxy war: On the one hand, Hezbollah and Iran are backed by Russia to support Assad, and on the other, key Gulf-Arab states are backed by the West to in turn fund and equip various rebels. There are the intense complications of Turkey's ever-shifting attitude to IS, the Kurds and even NATO. There's the continuing war in Iraq with its links to Syria – and to cap it all, there's the catastrophe that might ensue if Donald Trump somehow wins the U.S. presidential election.

All the while, ordinary Syrians are being injured and killed in their hundreds of thousands, and millions are still fleeing the country via dangerous, even lethal routes. A new cease-fire may technically be in place, but cause for optimism is thin on the ground.

![]()

Paul Rogers is a professor of peace studies at the University of Bradford. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.