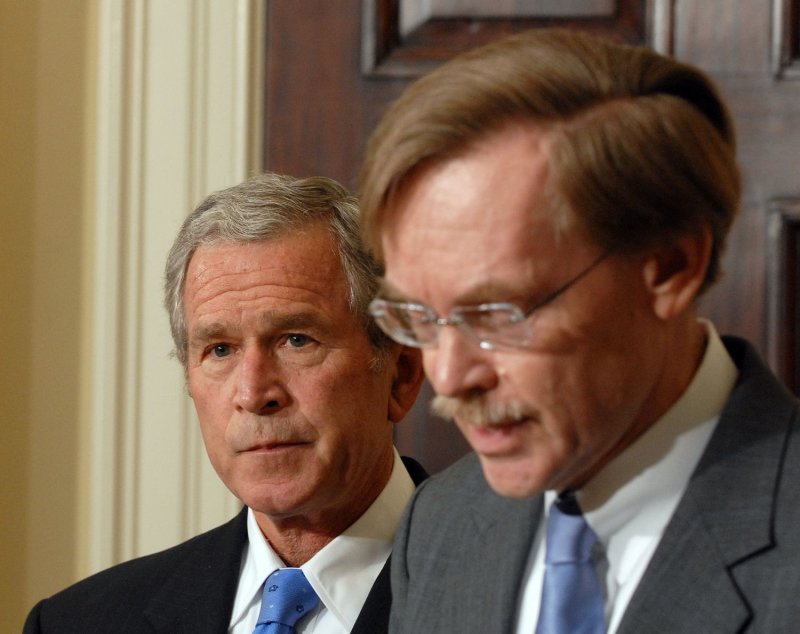

Robert Zoellick speaks after U.S. President George W. Bush announced Zoellick as his choice to be the next World Bank President from the Roosevelt Room of the White House on May 30, 2007. Zoellick is a former Deputy Secretary of State and U.S. Trade Representative. (UPI Photo/Roger L. Wollenberg) |

License Photo

LONDON, April 16 (UPI) -- France has fought a stubborn and increasingly desperate rearguard action for the past 30 years to protect its farmers against the competition of world markets through the mechanism of Europe's Common Agricultural Policy.

But suddenly, using the opportunity of the global food crisis, France is back on the offensive, saying Europe needs to guarantee its farmers higher prices and more protection in order to produce yet more food. Just ahead of this week's meeting of EU farm ministers in Luxembourg, three top French officials signaled the new policy by issuing a joint statement.

"Europe, with its high-performing farming sector and its common policy must clearly play a providing and regulating role on world food markets," said French Foreign Minister Bernard Kouchner, European Affairs Minister Jean-Pierre Jouyet and Human Rights Minister Rama Yade. "The increase in the cost of food paradoxically presents an opportunity, to revive investment in the farming sector."

There is no doubt of the scale of the crisis. Food prices in general have almost doubled in the last two years. Global stocks of wheat are down to their lowest levels in decades, governments like Egypt and India have imposed export curbs to keep their own food supplies at home, and the soaring price of rice has sparked riots across the globe.

World Bank President Robert Zoellick warned over the weekend the soaring cost of food was pushing 100 million people into poverty and threatening to reverse the economic gains made by developing countries.

"We have to put our money where our mouth is now, so that we can put food into hungry mouths. It is as stark as that," Zoellick said after a meeting of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank's Development Committee. "This is about ensuring that future generations don't pay a price, too."

The French response to this new mood of crisis was put by French Agriculture Minister Michel Barnier at the EU farm ministers' meeting in Luxembourg Monday. The real culprit, Barnier said, was the free-market ideology, and he argued that economic liberalism and "too much trust in the free market" were responsible for the world's food shortages and its higher prices.

"We must not leave the vital issue of feeding people to the mercy of market laws and international speculation," Barnier said. "In a world where it will be necessary to produce more and better to feed 9 billion people, everyone has got to play a part, including Europe."

This may be cunning politics from a French point of view. But in economic terms, it is nonsense. There is no such thing as a free market in food. Between them, the Americans, Europeans and Japanese spend almost $300 billion a year on subsidies for their farmers and use tariff barriers to prevent poor countries from taking advantage of their low labor costs to export cheap food to rich markets. Instead, rich countries subsidize their farmers to produce surpluses that are then exported (with further subsidies) to poor countries, often as cheap or free food aid, which destroys incentives for local farmers.

The rich world's refusal to give up its farm subsidies helps explain the failure of the Doha Round of the world trade talks. But even that is not the reason for the current food crisis. The main explanations are the rising prosperity of vast new markets in India in China. As people get richer and clamber up the prosperity chain, they also climb up the food chain, demanding meat protein instead of rice, hamburgers and American-style fried chicken instead of chapattis.

At the same time, the expansion of urban areas in Asia has eaten away at arable land and reduced local water tables. In East Africa and Latin America, prime arable land is no longer producing food staples for the local population, but exotic flowers and out-of-season fruits and vegetables for the wealthy consumers of the north. On top of all this, land that could grow food is now being subsidized in Europe and North America to grow crops that will be turned into expensive biofuels.

Over the weekend U.N. special rapporteur Jean Ziegler said this subsidy system for biofuels, a central feature of EU plans to tackle climate change, was a "crime against humanity."

France will take over the EU's rotating presidency at the end of June, giving it the right to set the agenda and chair the meetings of EU institutions for the next six months, a perfect opportunity to promote its new policy of more subsidies for more food production. In effect, France is seeking a return to the original concept of the CAP in the 1950s, when Europe's priority in the aftermath of World War II was to become self-sufficient once more in food.

But this would mean an end to the steady unwinding of the financial subsidies and quotas in the CAP that Britain, Germany and the Nordic countries have managed in recent years, in the teeth of French opposition. It would also mean a body blow to further liberalization of the global economy, a more protectionist and less efficient world. The answer to food shortages is fewer tariffs and more competition for farmers everywhere to sell wherever they can.