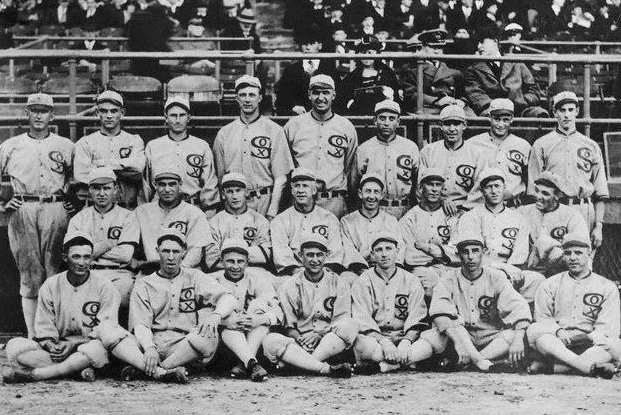

The 1919 Chicago White Sox finished first in the American League with an 84-56 record before losing the World Series to the Cincinnati Reds in eight games. Joe "Shoeless Joe" Jackson led the White Sox with a .351 batting average and 96 RBIs. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Oct. 9 (UPI) -- Players from the team are long gone, but tales remain from the Black Sox scandal from the 1919 World Series considered by many historians to be the darkest moment in America's pastime.

Wednesday marks the 100th anniversary of the end of that best-of-nine World Series, which the Cincinnati Reds won amid accusations of White Sox players taking bribes from gamblers in exchange for poor play.

Literature on the scandal is old and scattered, with websites and books devoted to debunking the common myths behind the Black Sox.

White Sox players Eddie Cicotte, Claude "Lefty" Williams, Arnold "Chick" Gandil, Charles "Swede" Risberg, George "Buck" Weaver, Oscar "Happy" Felsch, Fred McMullin and Joe "Shoeless Joe" Jackson were permanently banned from baseball for their roles in the fixing incident.

"It's an American story that's more than just baseball," said Dr. David Fletcher, co-founder of the Chicago Baseball Museum. "It's a story of redemption. Cheaters cheat cheaters. It's just a part of Americana."

Cicotte, Williams and Jackson admitted to a 1920 grand jury that they accepted the bribes. Felsch later admitted taking money. White Sox owner Charles Comiskey initially suspended seven of the players, while Gandil was not on the team at the time. Fletcher and other Black Sox experts estimate the players received at least $70,000 combined, but the actual amount probably will never be known.

"The one thing we know for sure is that they did not receive everything they were promised by the gamblers," said Jacob Pomrenke, the Black Sox Scandal Research Committee chairman for the Society for American Baseball Research.

Players banned

The players were acquitted of charges of conspiring with gamblers, but the first commissioner of baseball Major League Baseball -- appointed as a result of the scandal -- banned them for life a day after the verdict in 1921.

"Regardless of the verdict of juries, no player who throws a ballgame, no player that undertakes or promises to throw a ballgame, no player that sits in conference with a bunch of crooked players and gamblers where the ways and means of throwing a game are discussed and does not promptly tell his club about it, will ever play professional baseball," the commissioner, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, wrote.

The 1919 White Sox had the best record in the American League, with most of the players from their 1917 World Series winning team still on the roster. Jackson and several teammates missed the 1918 season because of World War I. The White Sox were big betting favorites entering the 1919 series against the up-and-coming Reds team.

Suspicions increased as the series progressed. Cicotte made a series of mistakes on the mound, leading the White Sox to a 9-1 loss in Game 1. The 1918 ERA title winner allowed six runs in the setback. Williams, who averaged 2.6 walks per nine innings for his career, walked three consecutive batters in Game 2, helping the Reds win 4-2.

The White Sox rebounded to win three of the next five games before losing 10-5 in Game 8. Comiskey first backed his players despite reporters investigating the bribes, offering a cash reward for information about the alleged fix. The White Sox owner later admitted to knowing about the scheme before the first game of the series.

Maintains innocence

Jackson hit .375 in the series and had 12 hits, putting his role in throwing the games up for debate. The lifetime .356 hitter maintained his innocence in regard to throwing the games throughout his life.

Several details of the fixed games still are debated among historians, due to inaccuracies from literature written about the series of events. Gandil admitted to being "one of the ringleaders" of the scandal in a 1956 Sports Illustrated article. He attributed the scandal to the team's dislike of Comiskey, whom he called out for his "cheapness." He also said baseball players at the time "mixed freely with gamblers" and "players often bet."

"For all their skill, the White Sox in 1919 weren't a harmonious club," Gandil said. "Baseball players in my day had a lot more cut-throat toughness, anyway, and we had our share of personal feuds, but there was a common bond among most of us: our dislike for Comiskey.

"I would like to blame the trouble we got into on Comiskey's cheapness, but my conscience won't let me. We had no one to blame except ourselves."

Despite the players' dislike for Comiskey, the traditional tale of underpaid ballplayers striking back at the owner has since been debunked by researchers, who found the White Sox to be one of the highest-paid teams in the league at the time.

Gandil admitted to meeting with Boston bookmaker Joseph "Sport" Sullivan about a week before the 1919 World Series, and he previously met Sullivan in 1912. Gandil also detailed tense moments before and during the series between the players and bookmakers. He said the players spoke to multiple gamblers during the series.

Tensions rise

Tension increased as reporters began to question the players about a potentially fixed series. Gandil said the players met and decided to try to win the series, despite the pressure from gamblers.

In the end, Gandil maintained the White Sox's series loss was "pure baseball fortune." He said he never received any part of a $10,000 bribe and did not know of any teammates who did.

"Our losing to Cincinnati was an upset all right, but no more than Cleveland's losing to the New York Giants by four straight in 1954," Gandil told Sports Illustrated. "Mind you, I offer no defense for the thing we conspired to do. It was inexcusable. But I maintain that our actual losing of the Series was pure baseball fortune."

Barred from Hall

Risberg was the last Black Sox player to die -- in 1975. He was 81. Jackson died in 1951. There have been multiple efforts to get the players reinstated into Major League Baseball, making them eligible for the Hall of Fame, but all have been turned down.

Fletcher leads a reinstatement campaign for Weaver, who has never admitted to taking money, but only meeting with his teammates to talk about the bribes. Weaver hit .324 and did not make any errors in the 1919 World Series.

Current MLB commissioner Rob Manfred upheld Weaver's ban in 2015, becoming the ninth commissioner to deny his re-entry to the game. Manfred denied the request on behalf of Weaver because of his presence at the meetings and awareness of the scheme to fix the World Series. Manfred also denied Jackson's request.

Researchers of the Black Sox continue to uncover new information in trying to figure out what actually happened.

"It's definitely a major piece of U.S. history that's more than just sports," Fletcher said. "It has so much there, as far as the romance about baseball ... sort of the theme of Field of Dreams, [that maybe] there is some redemption out there. These players basically got banished to the phantom zone."