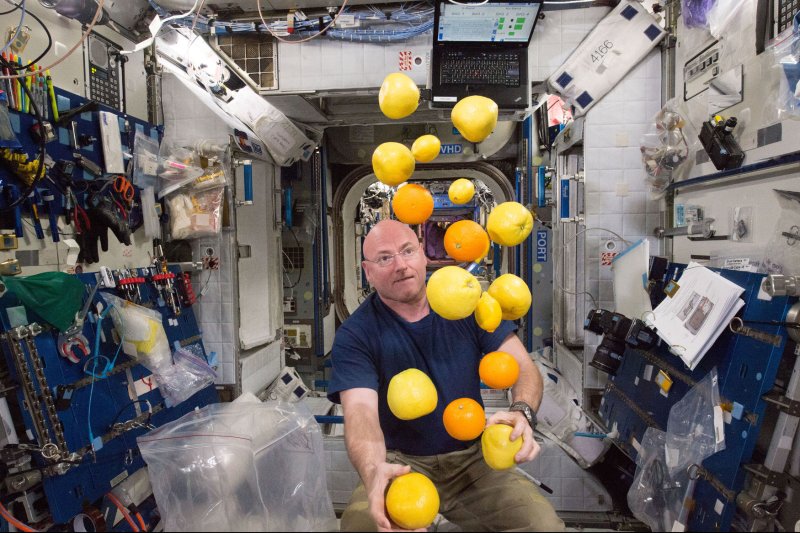

Spending prolonged periods of time under the microgravity conditions of space can cause a buildup of fluid in the brains of astronauts, according to a new study. Photo courtesy of NASA |

License Photo

Jan. 29 (UPI) -- Long-term space travel affects the human brain and at least two scientists think more work must be done to characterize the risks.

According to a new study published in the journal Neurology, astronauts who spend three to six months aboard the International Space Station showed signs of hydrocephalus, a buildup of cerebrospinal fluid inside the brain's ventricles.

The study's authors named the condition HALS, short for "hydrocephalus associated with long-term spaceflight."

Among patients on Earth, hydrocephalus triggers increased pressure in the head, often causing severe headaches. The condition can develop on its own, but it can result from tumor growth.

"Magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography scans of the brain also help to diagnose hydrocephalus in patients," lead researcher Donna Roberts, neuroradiologist at the Medical University of South Carolina, told UPI. "Various treatments exists depending on the type of hydrocephalus the patient is diagnosed with."

Now researchers have shown a similar condition can develop in the brains of astronauts.

For the study, Roberts and her colleague, Lonnie G. Petersen, doctor and researcher at the University of California San Diego, analyzed the brains of several dozen astronauts, before and after short and long space missions.

Some astronauts spent just a few weeks aboard the Space Shuttle, while others spent up to six months on ISS.

"We found that the astronauts who spent longer times in space had greater increases in the size of the ventricles on post-flight MRI compared with the preflight MRI," Roberts said. "The ventricles are the fluid-filled spaces in the center of the brain."

What scientists don't understand is whether HALS is a natural adaptive response to microgravity or whether it is a defect that warrants preventative measures or treatment. That's why scientists want more research to focus on the effects of microgravity on the human brain.

"We plan to compare the changes in brain structure that we have identified in the ISS astronauts with any change in their performance on tests of cognitive and motor abilities," Roberts said. "If the structural brain changes are associated with a decrement in performance, then NASA may need to develop countermeasures to mitigate the development of HALS for astronauts on long duration missions."

Roberts and her research partner hope NASA will spearhead new investigations into the development of HALS.

"We don't know if the brain fluid normalizes on its own, as the current NASA protocol does not include long-term follow-up brain imaging after some time back on Earth beyond the immediate post-flight MRI scan," Roberts said. "Obtaining long-term follow-up brain imaging using advanced MR techniques as well as physiological studies, including monitoring of cerebrospinal fluid pressure levels, would help to further understand HALS."