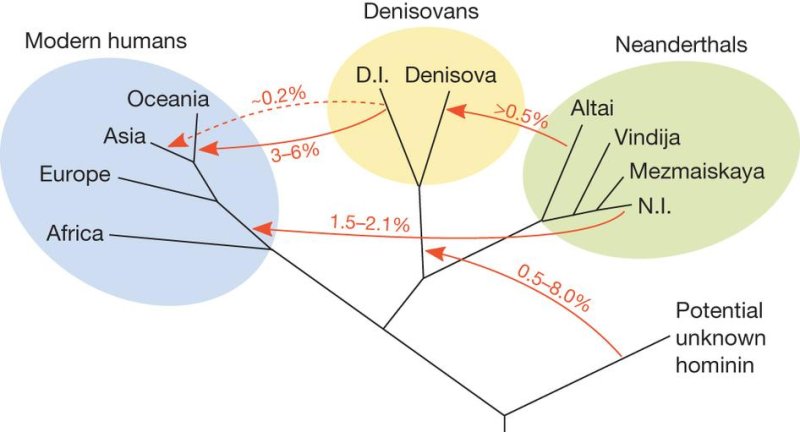

Above is a family tree of the four groups of early humans living in Eurasia 50,000 years ago and the gene flow between these groups due to interbreeding. Recent research has revealed that Neanderthals and Denisovans frequently interbred and occasionally did so with humans as well. (Credit: UC Berkley)

The most complete sequence of the Neanderthal genome shows inbreeding as well as interbreeding among at least four different types of early humans.

DNA extracted from the fossilized toe of a 50,000 year-old Siberian Neanderthal woman revealed that she was the child of two closely related parents, who were either half-siblings or double first cousins, the offspring of two siblings who married siblings.

Researchers found that Neanderthals and Denisovans, another type of early human, were closely related and that their common ancestor split off from the ancestor of modern humans around 400,000 years ago.

Further analysis suggests that the population sizes of Denisovans and Neanderthals were small, leading to interbreeding. Researchers also found evidence of interbreeding with a mysterious fourth type of early human.

The international team of anthropologists and geneticists published their findings in the journal Nature.

These two types of early humans eventually died out but left some of their genetic history because they occasionally interbred with modern humans. Researchers said that close to 1.5 to 2.1 percent of modern non-African genomes can be traced back to Neanderthals.

“The paper really shows that the history of humans and hominins during this period was very complicated,” said Montgomery Slatkin, a professor at UC Berkeley. “There was lot of interbreeding that we know about and probably other interbreeding we haven’t yet discovered.”

Graduate student Fernando Racimo found 87 specific genes that were significantly different from those found in Neanderthals and Denisovans, and could be the distinguishing factor between modern humans and their ancestors.

“There is no gene we can point to and say, ‘This accounts for language or some other unique feature of modern humans,’” Slatkin said. “But from this list of genes, we will learn something about the changes that occurred on the human lineage, though those changes will probably be very subtle.”

[UC Berkeley]

[Nature]