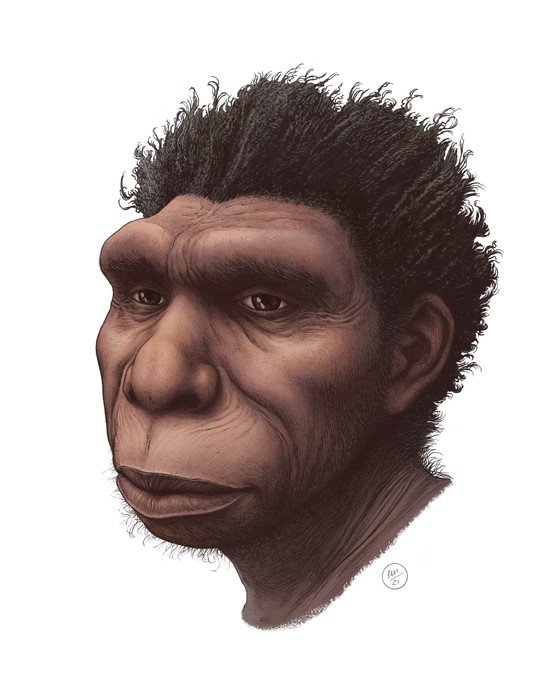

1 of 2 | Homo bodoensis, pictured in an artist's rendering, may not be the "missing link" in human evolution, but they are an important link explaining the origins and evolutionary development of the species. Illustration by Ettore Mazza

Oct. 28 (UPI) -- The link that early anthropologists hoped would neatly bridge the gap between apes and humankind probably doesn't exist, most scientists now agree. Human evolution, it turns out, looks more like a "braided stream" of diverging and converging lineages than an inclined plane of slowly improving posture.

To map this braided stream, one group of researchers urge a closer look at Middle Pleistocene hominins, a group that may help explain how Homo erectus, one of our earliest and most successful big-brained ancestors, became Homo sapiens.

In a new paper, published Thursday in the journal Evolutionary Anthropology Issues News and Reviews, researchers propose these important hominins -- thought to have emerged between 700,000 and 400,000 years ago -- be reclassified under a new name, Homo bodoensis.

These hominins may not be the "missing link," but they are an important one.

Over the last several decades, the complexity of human evolution has become increasingly apparent. By agreeing upon a new name and common definition, the researchers say it will be easier to trace the origins and movements of these early human ancestors.

A complex history

Complexity doesn't preclude clarity. But the braided stream of human evolution gets a bit muddy during the Middle Pleistocene.

The period stretches from 774,000 to 129,000 years ago -- a time when a diversity of hominins, sporting an odd mix of archaic and modern traits, walked the Earth -- not long after the lineages of modern humans and Neanderthal split.

According to the authors of the new study, anthropologists must start speaking the same language if they are to start making some sense of what researchers in the 1960s and 70s coined the "muddle in the middle."

Part of the problem, as the authors tell it, is that many of these Middle Pleistocene hominins, including remains found in Africa and Eurasia, are being classified under several species names -- some confusing, some contentious, some obsolete.

The authors propose a new name, Homo bodoensis, for a group of non-Neanderthal hominins spread though Africa, the Mediterranean and Eurasia.

"The point of the naming is that it allows us to build hypotheses that can be tested and that other scientists can understand," lead author Mirjana Roksandic, paleoanthropologist and professor at the University of Winnipeg, told UPI.

If different scientists have different definitions for hominin species, it becomes difficult to parse shared data and incorporate the findings of others into ongoing investigations.

"This is just opening the door to communicate and encourage the conversation around the movements of late Pleistocene hominins," Roksandic said.

Clarifying names, lineages

Most of the hominins that would be reclassified have been previously assigned to either Homo heidelbergensis or Homo rhodesiensis, the latter of which alludes to Rhodesia and the bloody legacy of European colonialism in Africa.

"Homo rhodesiensis is a bad name," John Hawks, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Wisconsin who was not involved in the new study, told UPI in an email.

"The legacy of colonial theft and extraction makes me pause," Hawks said.

But while the names Homo heidelbergensis or Homo rhodesiensis may be problematic or nonfunctional, their invention and sporadic use reflects the distinctiveness of these Middle Pleistocene hominins.

"There is a recognition that these hominins are not exactly Homo erectus, which preceded them," Roksandic said. "But they had not yet differentiated into modern humans, Neanderthals, Denisovans and other related lineages."

"Homo bodoensis is defined based on the specific combination of H. erectus-like, or primitive, and H. sapiens-like, or derived, morphological traits," co-first author Predrag Radović, researcher at the University of Belgrade in Serbia, told UPI in an email.

The confusion and miscommunication to which Roksandic and Radović speak is partly the result of evolutionary biology.

Despite their evolutionary progress, humans and their closest relatives retained numerous primitive traits -- morphological features that defined the different hominins that preceded them.

"You see more of these ancestral traits in Asian and African specimens than in Neanderthals, so this is where a lot of the confusion around Middle Pleistocene hominids come from," Roksandic said.

"Neanderthals are much more easily recognizable because they were the most diverged. They were developing in pseudo isolation in Europe," Roksandic said.

Recent DNA studies have shown that several specimens in Europe that had previously been classified as Homo heidelbergensis were actually early Neanderthals.

"It was the genetic data, amongst others, that prompted us to define the new species," Radović said. "DNA studies have revolutionized the field of paleoanthropology, especially in the last decade, and have shown that morphologically distinct species such as Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans freely exchanged genes."

Homo bodoensis features no Neanderthal-derived traits, but the would-be-species hosts many traits conserved in Homo sapiens.

No missing link

Though there is no magical missing link between ape and humankind, the authors of the latest paper argue there is an important link between Homo bodoensis and Homo sapiens -- and for scientists aiming to tell the complicated story of human evolution, it's a link that warrants further investigation.

As Roksandic and Radović tell it, Homo bodoensis was in the right place, at the right time and with the right combination of traits to be an important intermediary hominin species -- one that warrants an updated taxonomical classification.

"Taxa names -- especially so in paleontology -- are ultimately tools that enable scientists to organize morphological variation and communicate," Radović said.

The new, clearly defined species should help facilitate better communication among paleoanthropologists, the researcher said.

"Ultimately, we hope that our paper will start a wave of much needed taxonomic and conceptual revisions of hominin systematics," Radović said.

Plenty of names, not enough fossils

Not everyone is convinced of the need for a new species designation.

"I agree that many scientists are confused about the classification but I think adding yet another species name is not going to help," Hawks said. "The problem is not that we don't have enough names, it's that we don't have enough fossils."

Though there's always a need for new fossils, there are a lot more Middle Pleistocene hominin fossils than there were a half-century-ago, when scientists first began speaking of the muddle in the middle.

What those fossils have shown, Hawks argues, is that things weren't muddled, just complex. Early anthropologists were looking to consolidate several hundred thousand years of human evolution into a single global stage, but they didn't have the evidence.

"Today we know that 1970s-era view was just wrong," Hawks said. "It's not a muddle, it's a braided stream. We know that modern people descend from populations that were much more diverse than any populations living today."

Middle Pleistocene hominins were definitely unique, Hawks acknowledges, but there was so much mixing going on that he doesn't think it makes sense to try to organize that diversity under yet another species name.

"Convergence between these lineages was as important as divergence," he said. "Some of those African ancestors mixed repeatedly with Neanderthals, their descendants mixed with Denisovans."

"The way to make more progress is to find more fossils," Hawks said. "New names for old fossils are not helpful."

So what should these Middle Pleistocene hominins be called? Hawks thinks it makes more sense to simply call these hominins, with brains the size of modern humans, Homo sapiens.

This, he said, would allow scientists to spend less time worrying about taxonomic classification and more time illuminating this unique period of admixing, convergence and divergence among hominins.

"We should be working to find better ways to talk about networks of populations, not imposing an outmoded way of looking at our evolution," Hawks said.