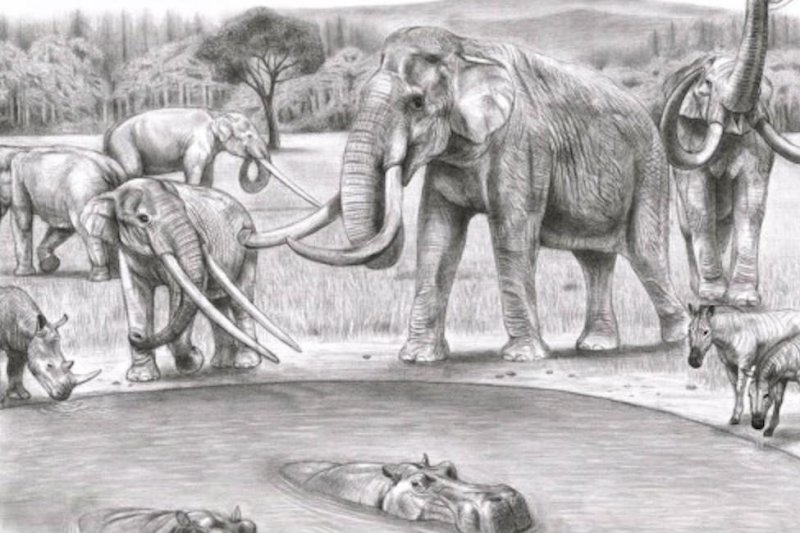

Less than 2 million years ago, a variety of prehistoric elephant species were found throughout Europe and Asia -- but researchers say humans are not the only reason many of them are extinct. Photo by Tamura Shuhei

July 1 (UPI) -- Sudden and dramatic environmental shifts, triggered by climate change, fueled the decline of prehistoric elephants, mammoths and mastodonts -- and humans likely played only a minor role in their demise -- according to a new study.

For decades, hunter gatherers have served as the primary suspect in the case of the planet's disappeared megafauna.

After all, their descendants, modern humans, have severely degraded Earth's ecosystems and snuffed out dozens of plant and animal species.

But the latest findings -- published Thursday in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution -- suggest the emergence of small bands of spear-wielding humans fails to explain the rise and fall of the elephants, prehistoric and otherwise.

Still, there were once many more big animals than there are today.

Thousands of years ago, a wide variety of large proboscideans -- the group of large herbivores that includes mammoths and mastodons -- roamed the planet.

Today, only three species remain, all of them endangered and relegated to the tropics of Asia and Africa.

To better understand the evolutionary history of elephants and their relatives, an international team of paleontologists conducted an exhaustive review of the adaptive characteristics evolved by 185 different proboscidean species.

The review included dental and cranial features, mastication methods, tusk size, body mass and locomotion, among other characteristics.

This analysis allowed scientists to gain a better appreciation for the wide variety of forms and ecologies that proboscideans adopted during the millions of years before the arrival of early humans.

Using sophisticated statistical techniques, researchers modeled the emergence of these various adaptions across time and space.

"We discovered that the ecological diversity of proboscideans increased drastically once they dispersed from Africa to Eurasia approximately 20 million years ago and to North America approximately 16 million years ago, when land connections between these continents formed," study co-author Steven Zhang told UPI in an email.

"Diversity also increased in Africa following these events," said Zhang, a research associate at the University of Bristol in England.

Before this exodus, the prehistoric proboscideans of ancient Africa evolved rather slowly.

In fact, the proboscideans of the Oligocene, the epoch that began some 33 million years ago, didn't look all that much like elephants, and most of the morphological experiments were evolutionary dead ends.

Once these archaic North African lineages escaped into Europe and Asia, proboscidean evolution accelerated by a factor of 25 as prehistoric elephants quickly adapted to capitalize on a bounty of ecology opportunities.

Unfortunately, the boom times don't last forever. In addition to revealing the timing of proboscidean diversification, the analysis also revealed periodic declines in proboscidean speciation.

"From approximately 6 million years ago, and especially since 3 million years ago, the ecomorphological diversity of proboscideans started to decrease globally in increments, following events of climatic cooling and harshening," co-author Juha Saarinen, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Helsinki in Finland, told UPI in an email.

According to the authors of the new study, humans fail to explain these periodic declines.

"For instance, in Africa we see the big proboscidean extinction pulse about 2.4 million years ago, when members of the evolving hominin lineage were still very much bipedal chimpanzees in terms of their functional ecology," Zhang said.

"The final proboscidean extinction surges we detected on various continents do not go hand in hand with either enhanced hunting capabilities in archaic hominins or the settlement of Homo sapiens on the different landmasses," Zhang said.

The latest findings don't rule out all human influence on proboscidean extinctions, researchers said, but they do suggest a heightened risk of proboscidean extinction emerged in Africa, Eurasia and the Americas before the arrival of big-game-hunting humans.