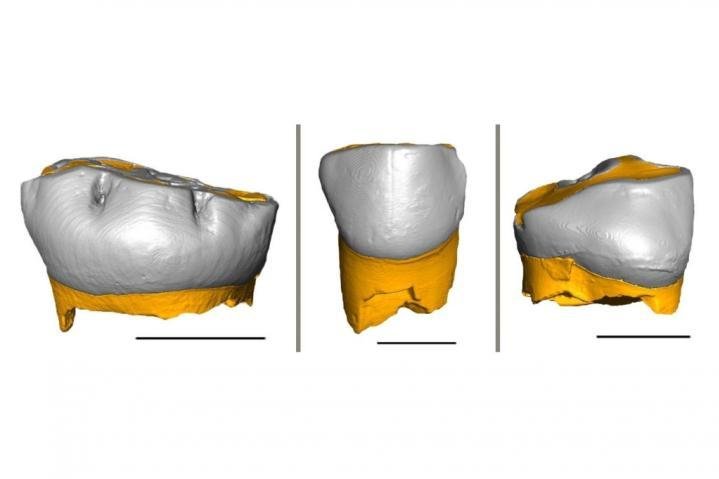

By analyzing ancient milk teeth, researchers were able to determine how fast young Neanderthal children grew. Photo by Federico Lugli

Nov. 2 (UPI) -- Neanderthal children grew at the same rates and were weaned at roughly same age as Homo sapien children, according to a new study published Monday in the journal PNAS.

Scientists were able to discern the growth rates and weaning onset times of Neanderthal children by examining milk teeth fossils recovered from northern Italy. The fossil teeth belonged to three different Neanderthal children living between 70,000 and 45,000 years ago.

Teeth form discrete layers as they develop, like a tree's growth rings. Each layer, or ring, preserves chemical details that can provide insights into an individual's diet and environmental circumstances.

Scientists used a laser-mass spectrometer to measure chemical signatures, including strontium concentrations, in the layers of the ancient milk teeth. The data showed Neanderthal parents began introducing solid foods to their children when they were around five or six months old.

The new findings suggest weaning onset is physiological phenomena, not a cultural one.

"In modern humans, in fact, the first introduction of solid food occurs at around six months of age when the child needs a more energetic food supply, and it is shared by very different cultures and societies," study author Alessia Nava, anthropologist and research fellow at the University of Kent in Britain, said in a news release.

"Now, we know that also Neanderthals started to wean their children when modern humans do," said Nava, an anthropologist and research fellow at the University of Kent in Britain.

Researchers hypothesize that the high energy demands of human brain development is responsible for the early introduction of solid foods in the diets of Neanderthal and Homo sapien children.

The similarities between growth rates and the timing of weaning Neanderthal and Homo sapien children suggests Neanderthal newborns were likely of similar weight to modern human newborns.

The milk teeth analyzed for the study were recovered from a trio of cave sites in northeastern Italy. In addition to revealing the growth rates and diets of infants, the chemical makeup of the ancient teeth also offered scientists a sense of these Neanderthals' regional mobility.

"They were less mobile than previously suggested by other scholars," said co-author Wolfgang Müller.

"The strontium isotope signature registered in their teeth indicates in fact that they have spent most of the time close to their home: this reflects a very modern mental template and a likely thoughtful use of local resources," said Müller, researchers at Goethe University Frankfurt in Germany.

Researchers suspect northeastern Italy's rich ecological diversity and variety of food sources allowed Neanderthals to persist -- without doing too much moving around -- in the region until at least 45,000 years ago.

According to the study's authors, the new findings undermine previously published hypotheses suggesting late weaning age contributed the demise of Neanderthals.