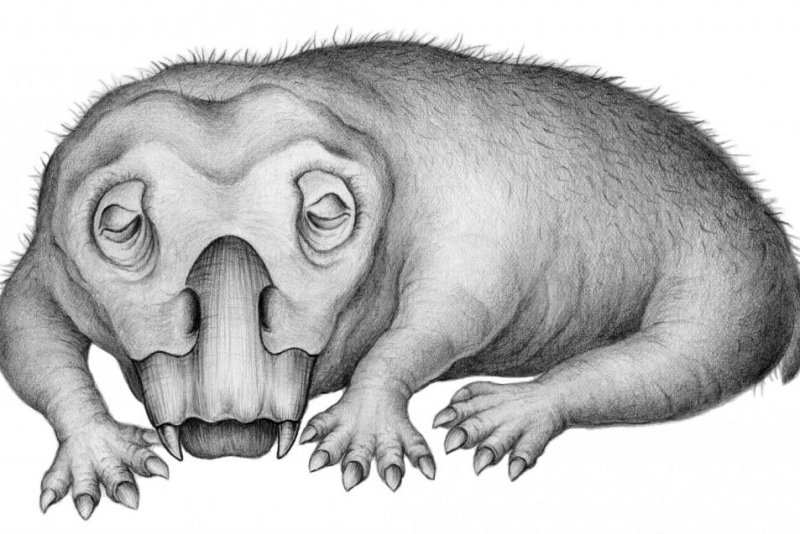

Members of the genus Lystrosaurus were stout, four-legged foragers that new research suggests went into a hibernation-like state during winters in Antarctica.

Illustration by Crystal Shin

Aug. 27 (UPI) -- Paleontologists have unearthed fossil evidence of hibernation in Antarctica that suggest animals have been using torpor for at least 250 million years, according to a study published Thursday in the journal Communications Biology.

Torpor is another name for hibernation, during which animals lower their body temperatures and metabolic rates for long periods of time -- effectively sleeping away the winter.

Scientists discovered the hibernation-like state in a member of the genus Lystrosaurus, a distant relative of mammals. The stubby, pig-like animal first emerged in the fossil record not long before the end of the Permian Period, which was marked by a mass extinction event that wiped out 70 percent of land-based vertebrates.

Lystrosaurus species survived, spreading across Earth's single, giant continent, Pangea, during the first 5 million years of the Triassic Period. The four-legged forager even established itself in the most frigid parts of Pangea, the parts that became Antarctica.

Scientists were able to the discover the animal's hibernation by studying its tusks, the cross sections of which contain records of metabolism, growth and stress.

For the study, researchers compared patterns in the tusk cross sections of Antarctic Lystrosaurus specimens to those from four Lystrosaurus specimens unearthed in South Africa.

"The fact that Lystrosaurus survived the end-Permian mass extinction and had such a wide range in the early Triassic has made them a very well-studied group of animals for understanding survival and adaptation," study co-author Christian Sidor, professor of biology at the University of Washington and curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Burke Museum, said in a news release.

During the Early Triassic, the Lystrosaurus of Antarctica and South Africa were separated by 550 miles. The southern regions of Pangea were well within the Antarctic Circle. Though Earth was warmer during this period, the southern-most parts of Pangea would have still experienced prolonged periods without sun.

Among the tusks belonging to Antarctic Lystrosaurus, researchers found thick, closely spaced rings representing prolonged periods of stress. The same markings were absent or less pronounced among tusks from farther north.

"The closest analog we can find to the 'stress marks' that we observed in Antarctic Lystrosaurus tusks are stress marks in teeth associated with hibernation in certain modern animals," said lead study author Megan Whitney, a postdoctoral researcher at Harvard University who conducted the research while a doctoral student in biology at Washington.

Animals practice torpor to different degrees. Researchers can't be sure whether Lystrosaurus engaged in a weeks-long reduction in metabolism, body temperature and activity or relied on a shorter, more subtle version of torpor.

Many of the other vertebrates from the Triassic, with a geographical range similar to Lystrosaurus -- species that might help scientists confirm the ancient roots of hibernation -- didn't have tusks or continuously growing teeth.

"To see the specific signs of stress and strain brought on by hibernation, you need to look at something that can fossilize and was growing continuously during the animal's life," said Sidor. "Many animals don't have that, but luckily Lystrosaurus did."

Researchers plan to continue comparing the cross sections of Lystrosaurus tusks from different parts of Pangea, with hopes that a more robust pattern emerges -- evidence of hibernation's ancient evolutionary roots.

"Cold-blooded animals often shut down their metabolism entirely during a tough season, but many endothermic or 'warm-blooded' animals that hibernate frequently reactivate their metabolism during the hibernation period," said Whitney. "What we observed in the Antarctic Lystrosaurus tusks fits a pattern of small metabolic 'reactivation events' during a period of stress, which is most similar to what we see in warm-blooded hibernators today."