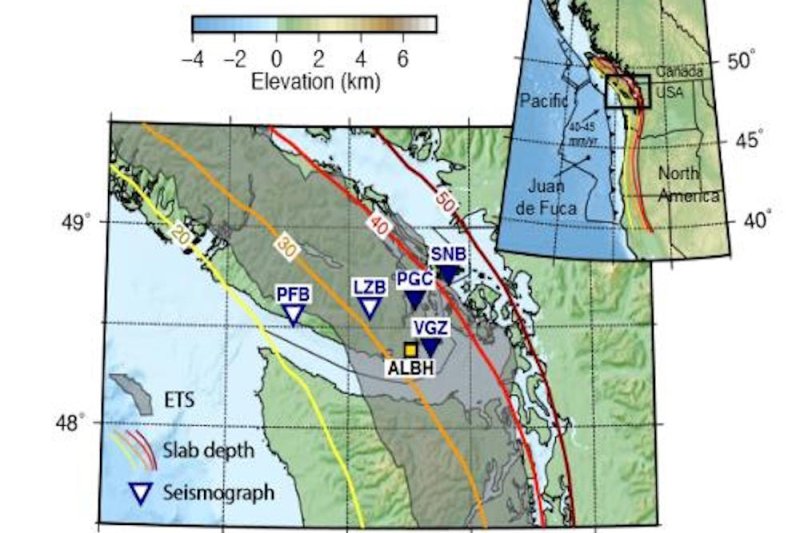

A map of Vancouver Island shows the locations of seismic instruments considered by the research group. The grey shaded region delineates where slow earthquakes occur.

Photo courtesy of University of Ottawa

Jan. 24 (UPI) -- Researchers have identified the origins of slow earthquakes, or slowquakes, a unique type of earthquake discovered just 20 years ago.

Slow earthquakes, which can last days or months, don't produce large seismic waves or trigger tsunamis. Imperceptible on land, these deep-lying quakes occur as one tectonic plate slips over another at subduction zone faults.

A team of researchers at the University of Ottawa in Canada wanted to find out why these slow-moving quakes behave so much differently than those that occur closer to the surface.

"Our work presents unprecedented evidence that these slow earthquakes are related to dynamic fluid processes at the boundary between tectonic plates," study author Jeremy Gosselin, an Ottawa doctoral student, said in a news release. "These slow earthquakes are quite complex, and many theoretical models of slow earthquakes require the pressure of these fluids to fluctuate during an earthquake cycle."

Using imaging technology similar to ultrasound, scientists were able to survey slow earthquakes and study the geologic structures surrounding the subduction zone faults where they occur. Scientists also considered the unique properties of the kinds of rocks found along these deep-lying faults.

One of the study's authors, Pascal Audet, an associate professor of geophysics at the University of Ottawa, had previously discovered a link between slow earthquakes and faults featuring especially high fluid pressures.

"The rocks at those depths are saturated with fluids, although the quantities are minuscule," said Audet. "At a depth of 40 kilometers, the pressure exerted on the rocks is very high, which normally tends to drive the fluids out, like a sponge that someone squeezes. However, these fluids are imprisoned in the rocks and are virtually incompressible; the fluid pressure therefore rises to very high values, which essentially weakens the rocks and generates slow earthquakes."

Though researchers have previously proposed that sudden changes in fluid pressures might explain the triggering of slowquakes, but until now, scientists had no empirical evidence for the theory.

"What we discovered confirmed our suspicions and we were able to establish the first direct evidence that fluid pressures do, in fact, fluctuate during slow earthquakes," said researcher Jeremy Gosselin.

The research team published the results of their slowquake survey this week in the journal Science Advances.