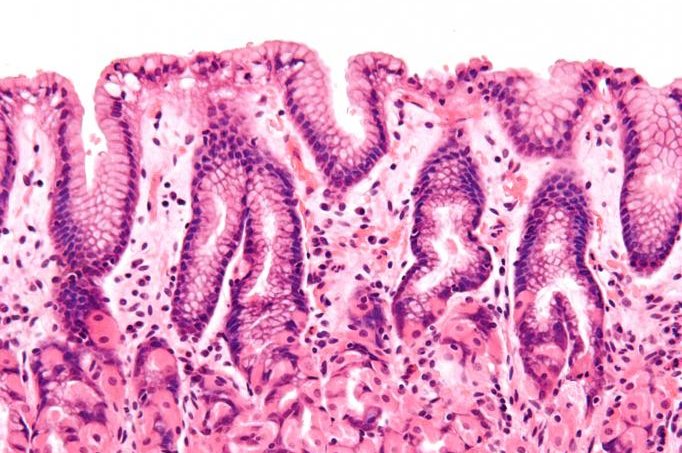

The intestinal wall, or epithelium barrier, ensures harmful pathogens can't escape from the guts into other parts of the body. Photo by Nephron/

Wikimedia Commons

Nov. 27 (UPI) -- The lining of the human intestine prevents potentially harmful bacteria, fungi and viruses that entered via consumed food from invading other parts of the body. New research suggests spending time in microgravity weakens what's known as the epithelial barrier.

"Our findings have implications for our understanding of the effects of space travel on intestinal function of astronauts in space, as well as their capability to withstand the effects of agents that compromise intestinal epithelial barrier function following their return to Earth," Declan McCole, a professor of biomedical sciences at the University of California, Riverside, said in a news release.

Spending long periods of time in space can negatively affect the health of astronauts in a variety of ways. Under microgravity conditions, muscles and bones atrophy and the immune system becomes depressed. Previous studies suggest time in space can impact human vision and the brain's gray matter, as well as increase an astronaut's susceptibility to food-borne pathogens like salmonella.

"Our study shows for the first time that a microgravity environment makes epithelial cells less able to resist the effects of an agent that weakens the barrier properties of these cells," McCole said. "Importantly, we observed that this defect was retained up to 14 days after removal from the microgravity environment."

For their study, scientists observed the effects of acetaldehyde, an alcohol metabolite, on epithelial cells under both normal and microgravity conditions. Alcohol is known to increase gastrointestinal permeability.

Researchers place epithelial cells in a rotating wall vessel, a bioreactor that keeps cells in a precise rotation, to simulate weightlessness.

After 18 days in the vessel, the epithelial cells had failed to form what scientists call "tight junctions," the connections between cells that ensure impermeability. Once removed, the cells struggled to develop proper tight junction patterns for an additional 14 days.

Researchers published the results of their study this week in the journal Scientific Reports.

"Our study is the first to investigate if functional changes to epithelial cell barrier properties are sustained over time following removal from a simulated microgravity environment," McCole said. "Our work can inform long-term space travel and colonization where exposure to a food-borne pathogen may result in a more severe pathology than on Earth."