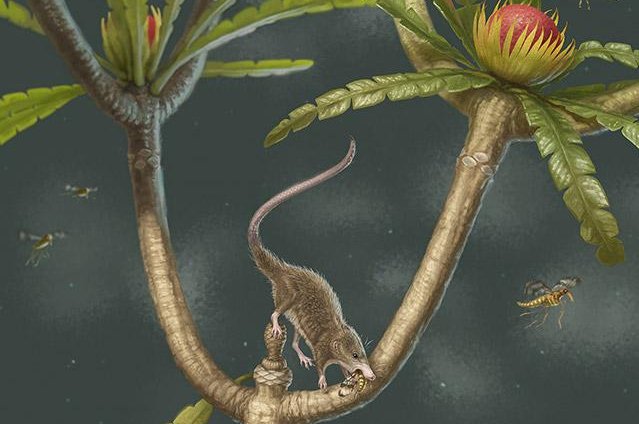

An ancient shrew-like, tree-dwelling species was one of the earliest mammalian ancestors to boast U-shape hyoid bones. Photo by April Neander/University of Chicago

July 18 (UPI) -- Unlike reptiles and birds, which scarf down large chunks of food or even swallow prey whole, most mammals chew before they swallow. The discovery of the 165-million-year-old remains of a shrew-like animal, Microdocodon gracilis, suggests some of the earliest ancestors of modern mammals chewed before they swallowed, too.

The newly found Jurassic fossil features the earliest known example of the hyoid bones deployed by modern mammals. Hyoid bones connect the back of the mouth to the esophagus. In mammals, the bones are suspended by jointed segments from the skull to form a U-like shape. They provide the tongue and throat muscles with the mobility necessary to transport and swallow chewed food.

"Mammals have become so diverse today through the evolution of diverse ways to chew their food, weather it is insects, worms, meat, or plants. But no matter how differently mammals can chew, they all have to swallow in the same way," Zhe-Xi Luo, a professor of biology and anatomy at the University of Chicago, said in a news release. "Essentially, the specialized way for mammals to chew and then swallow is all made possible by the agile hyoid bones at the back of the throat."

While other vertebrates have hyoid bones, they are simple and rod-like. The same kinds of sophisticated chewing technique used be mammals would be impossible with such a rigid structure supporting the tongue and throat.

Until now, scientists were unsure of the evolutionary origins of U-shaped hyoid bones. The latest discovery, detailed this week in the journal Science, suggests Microdocodon gracilis was one of the earliest species to deploy the evolutionary adaptation.

"It is a pristine, beautiful fossil. I was amazed by the exquisite preservation of this tiny fossil at the first sight. We got a sense that it was unusual, but we were puzzled about what was unusual about it," Luo said. "After taking detailed photographs and examining the fossil under a microscope, it dawned on us that this Jurassic animal has tiny hyoid bones much like those of modern mammals."

Microdocodon gracilis is a docodont, an extinct lineage of mammaliaforms, which is a group of early mammalian ancestors from the Mesozoic era. Scientists used CT scans, computer simulations and 3D casts of the fossil to better understand both its ecological and evolutionary history.

Though the species boasts a middle ear bone still attached to the jaw, a primitive feature, its hyoids already resembled those of modern mammals.

"Hyoids and ear bones are all derivatives of the primordial vertebrate mouth and gill skeleton, with which our earliest fishlike ancestors fed and respired," said Bhart-Anjan Bhullar, a postdoctoral researcher at Yale University. "The jointed, mobile hyoid of Microdocodon coexists with an archaic middle ear -- still attached to the lower jaw. Therefore, the building of the modern mammal entailed serial repurposing of a truly ancient system."

The species' lightweight, long tail and nimble limb bones resemble those of a tree-dweller, while its teeth suggest M. gracilis ate mostly insects.

"Its limb bones are as thin as matchsticks, and yet this tiny Mesozoic mammal still lived an active life in trees," said April Neander, a scientific artist at the University of Chicago.