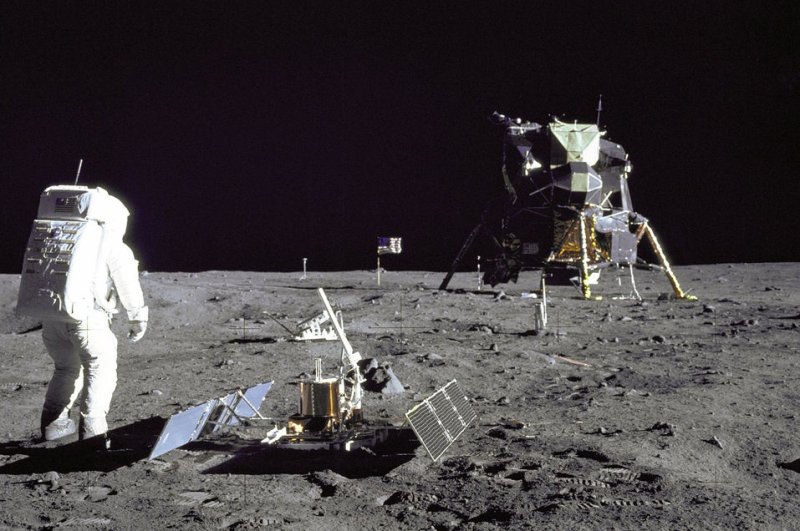

1 of 7 | Astronaut Edwin E."Buzz" Aldrin Jr. is seen during the Apollo 11 extravehicular activity on the surface of the moon on July 20, 1969. While Aldrin, Neil Armstrong and Michael Collins brought back nearly 50 pounds of rock samples, making it to the moon was the primary scientific objective of the Apollo 11 mission. File Photo by NASA |

License Photo

June 17 (UPI) -- In 1961, when President John F. Kennedy called on the United States to put a man on the moon by the end of the decade, he wasn't inspired by a curiosity about the moon's formation.

Kennedy felt the intense pressure of the Cold War, and in the wake of Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin becoming the first human in space, Kennedy called on the United States to "catch up to and overtake" the Soviet Union in the so-called space race.

"This was war by another means," Roger Launius, former chief historian of NASA, told UPI.

Today, dozens of scientific experiments regularly travel to and from the International Space Station, and each new NASA mission features an array of scientific instruments and objectives. But during the early 1960s, NASA wasn't sure if space exploration beyond near-Earth-orbiting satellites -- let alone scientific exploration of the moon -- was even possible.

"The point of Apollo 11 was to meet Kennedy's commitment," said John Logsdon, space historian and a professor of political science and international affairs at George Washington University. "Anything else that would have interfered or complicated the success of the mission wouldn't have been given priority."

Apollo 11's scientific mission, Logsdon contends, was secondary and non-essential.

"Apollo 11 went to land on the safest place on the moon," Logsdon said. "It was also, scientifically, probably the least interesting place you could go."

Mare Tranquilitatis, or the Sea of Tranquility, where Apollo 11 touched down on July 20, 1969, is one of the oldest, flattest lunar regions. For engineers, big, flat lunar plains without much differentiation are the best bet for safely landing spacecraft.

"But it's not good for collecting lots of different kinds of rocks and soil samples," Launius said.

Even if Apollo's scientific mission was secondary -- an afterthought, even -- it was still significant.

"The science was actually huge even though it was not the primary goal of the mission," said science journalist and space historian Andrew Chaikin.

In addition to setting foot on the moon, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin collected 47.5 pounds of lunar material and brought it back to Earth. The lunar samples allowed scientists to test a variety of hypotheses about the moon's formation and history.

Prior to the moon landing, there was still some debate about whether the moon was a cold fossil, a frozen relic, or a planetary body that had experienced volcanic activity.

"The Apollo 11 samples proved without a doubt that the moon had been volcanically active," Chaikin said.

There were even some scientists who argued the moon was covered in a thick layer of dust. The Apollo 11 astronauts, they predicted, would sink into the surface upon leaving the lander. The prediction, obviously, proved false.

Prior to Apollo 11, lunar scientists weren't certain about much. Scientists weren't sure whether the moon was young or old, or if it was composed of the same materials as Earth or something different.

The samples collected by Armstrong and Aldrin helped settle these basic scientific questions.

"Most importantly, the lunar samples proved the moon had underground differentiation, it's materials had become hot enough to melt and separate into layers," Chaikin said. "In the Apollo 11 samples, there were very small grains of anorthocite -- remnants of the original crust that formed after the molten moon first cooled."

The Apollo 11 mission also confirmed the moon was indeed an ancient object -- its rocks as old as Earth's -- and that it could be, according to Chaikin, a kind of "Rosetta stone for decoding the earliest years of the solar system."

"The Apollo 11 samples also revealed the critical role large impacts play in the evolution of young planets and moons," Chaikin said.

One of the things scientists first noticed when they got lunar rock samples under microscopes back on Earth was that all the water was gone.

"They were absolutely bone dry," Chaikin said. "Scientists couldn't find water molecules chemically bound to the minerals inside the moon rocks."

The revelation confirmed that the moon had failed to hold onto any significant stores of volatiles, which suggested the moon was the product of a massive collision between Earth and another planetary body.

Despite the lack of water, the first moon rocks proved Earth and its moon shared a common geologic ancestry. However, isotopic analysis also proved the two bodies were distinct.

But it's true that Apollo 11 wasn't a scientific mission. The United States and its space agency put a man on the moon to prove that it could -- to demonstrate its engineering and technological might.

"The great legacy of Apollo was pulling this thing off under a deadline," Chaikin said. "The country funded an experiment in how to do hard things with large numbers of people."

The feat set the stage for future space missions.

"It was a necessary step for future missions for which you could plan different activities, like scientific investigation and exploration," Logsdon said. "After 11, there were advertised scientific objectives for each mission."

"Each of the Apollo missions were designed to be more extensive and involved than the one before," Launius said. "Each of those of missions did more than the last."

By the time of Apollo 15, mission astronauts were outfitted with a lunar rover.

"Once you've got the lunar rover, you can move," Launius said. "The Apollo 15 astronauts traveled more than 20 miles, and they were able to go over to places that were scientifically interesting."

While the scope of NASA's scientific missions steadily increased in the wake of Apollo 11, the agency's budget did not. By the time Armstrong and Aldrin made history, NASA's budget was already falling. After peaking in 1965, the agency's budget shrank for a decade before stabilizing.

Today, NASA is once again trying to manage an array of ambitious scientific space missions, while meeting the president's call for a return to human spaceflight. Of course, NASA has proven it can send astronauts to the moon. Now, the agency wants to go to the moon and stay there.

"The real question is: Can we go back to the moon and do in a way that's sustainable and cost-effective," Chaikin said.