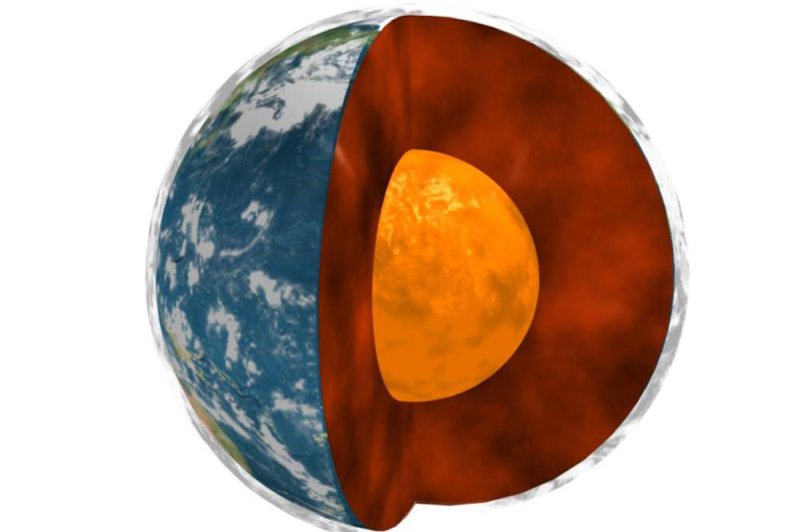

The mantle, which is sandwiched between Earth's crust and the outer core, is some 1,800 miles thick. Photo by JPL/NASA

June 6 (UPI) -- Scientists assumed Earth's mantle, the layer stretching from the crust to a depth of 255 miles, was magnetically dead. New research suggests they were mistaken.

Most scientists thought Earth's magnetism was powered by materials in the crust and core, but according to a new study published this week in the journal Nature, hematite, a common iron oxide, retains its magnetic qualities at high temperatures.

"This new knowledge about the Earth's mantle and the strongly magnetic region in the western Pacific could throw new light on any observations of the Earth's magnetic field," Ilya Kupenko, mineral physicist and researcher from the University of Munster in Germany, said in a news release.

Earlier this year, scientists had to complete an early update of the World Magnetic Model, a map of Earth's magnetic fields that powers a variety of global navigational systems, after Magnetic North began shifting and behaving erratically. The ordeal offered a reminder of how little scientists understand the movement of magnetic materials inside Earth's interior.

The latest research, however, could help scientists begin to explain some of the planet's electromagnetic anomalies.

Most of Earth's magnetism comes from the flow of liquid iron alloys inside the planet's core. Rocks in the crust also give off magnetic signals. But until now, researchers thought minerals lost their magnetism inside the mantle as a result of the extreme heat and high pressures.

But when, in a series of lab tests, scientists subjected iron oxides to temperatures and pressures comparable to the conditions deep inside the mantle, they found hematite remained magnetic up to a temperature of 925 degrees Celsius.

"As a result, we are able to demonstrate that the Earth's mantle is not nearly as magnetically 'dead' as has so far been assumed," said Carmen Sanchez-Valle, professor at the Institute of Mineralogy at Munster University. "These findings might justify other conclusions relating to the Earth's entire magnetic field."

Every few hundred thousand years, Earth's magnetic poles flip. Scientists studying Earth's electromagnetic history have previously estimated Earth's magnetic poles migrate across the Pacific. The hypothesis is based on the analysis of ancient rock records and electromagnetic anomalies measured in the ocean floor. The latest research, however, suggests those anomalies could be explained by the movement of hematite-containing rocks in the Earth's mantle beneath the West Pacific.

"What we now know -- that there are magnetically ordered materials down there in the Earth's mantle -- should be taken into account in any future analysis of the Earth's magnetic field and of the movement of the poles," said Leonid Dubrovinsky, professor at the Bavarian Research Institute of Experimental Geochemistry and Geophysics at Bayreuth University.