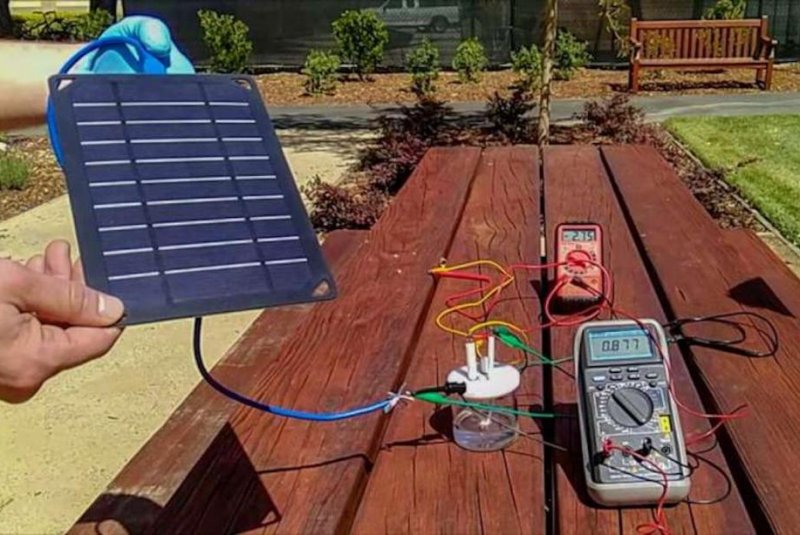

Scientists used a new solar-powered device to split seawater into oxygen and hydrogen. Photo by H. Dai, Yun Kuang, Michael Kenney

March 19 (UPI) -- Scientists at Stanford University have developed a way to turn seawater into hydrogen fuel using solar power and electrodes.

Current water-splitting technologies used to generate hydrogen fuel require highly purified water. The creation of a hydrogen economy would require "so much hydrogen it is not conceivable to use purified water," according to Stanford researchers Hongjie Dai, J.G. Jackson and C.J. Wood.

Because hydrogen fuel doesn't release CO2 when it is burned, many see hydrogen fuel as a potentially climate-friendly replacement for fossil fuels.

Using electricity to split water molecules, a process called electrolysis, isn't new. When electricity is run through electrodes in water, hydrogen gas bubbles out of the cathode, or negative end, while pure oxygen emerges from the anode, or positive end.

When seawater is used, negatively charged chloride can corrode the anode. But in proof-of-concept experiments conducted in the Dai lab, Stanford researchers used layers rich in negative charges to repel chloride and protect anodes from corrosion.

Scientists built the layered anode using layers of nickel-iron hydroxide and nickel sulfide, covering a nickel foam core. The foam works as a conductor, delivering electricity to the nickel-iron hydroxide, which triggers electrolysis. The water-splitting reaction causes nickel sulfide to evolve into a negatively charged layer, which repels chloride and protects the core metal.

In seawater, a standard anode lasts just 12 hours.

"The whole electrode falls apart into a crumble," Michael Kenney, a graduate student in the Dai lab, said in a news release. "But with this layer, it is able to go more than a thousand hours."

For the first set of experiments, scientists controlled the amounts of electricity being fed into the water-splitting electrodes. For their second proof-of-concept experiment, researchers built a water-splitting device powered by solar panels. Scientists used the device to turn seawater from the San Francisco Bay into oxygen and hydrogen.

"The impressive thing about this study was that we were able to operate at electrical currents that are the same as what is used in industry today," Kenney said.

Researchers described their feat in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Scientists hope industrial researchers can develop ways to scale and commercialize the new technology. In the future, the device could be used to do more than generate fuel. The water-splitting technology could also be used to generate oxygen for divers and submarines deep below the ocean's surface.