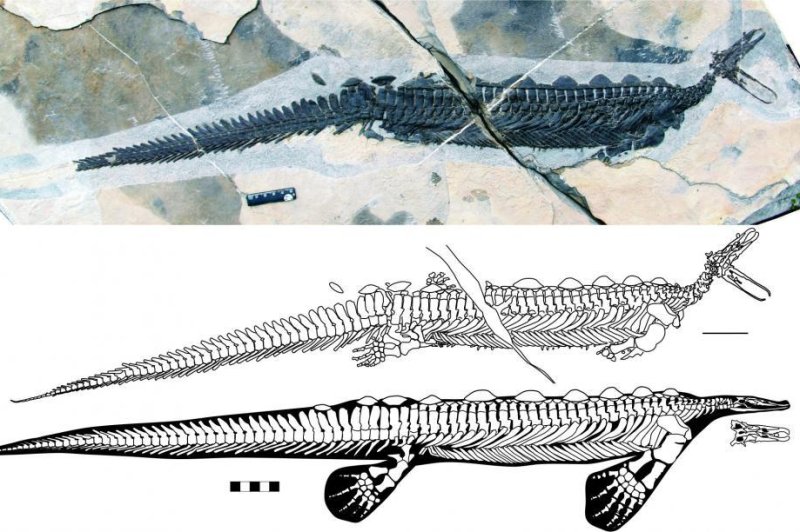

Scientists have recovered the skull of an ancient marine reptile. Like the modern day platypus, Eretmorhipis carrolldongi used a duck bill to hunt small prey. Photo by Long Cheng, et al./Scientific Reports 2019/Creative Commons 4.0

Jan. 28 (UPI) -- Scientists have recovered the remains of an ancient duck-billed reptile in China. The platypus-like species swam Asia's shallow seas during the early Triassic, some 250 million years ago.

The newly discovered species belongs to an extinct genus of hupehsuchian marine reptile called Eretmorhipis. Scientists have recovered a handful of Eretmorhipis specimens, but only partial fossils and never a skull.

Now, scientists know at least one Eretmorhipis species posted a duck bill.

The reptile measured just 27 inches long and featured a slender, rigid body. Four fan-like flippers helped the marine reptile maneuver, while bony plates running down its back offered protection. Its small skull boasted tiny eyes.

"This is a very strange animal," Ryosuke Motani, a paleontologist at the University of California, Davis, said in a news release. "When I started thinking about the biology I was really puzzled."

Scientists think Eretmorhipis carrolldongi lurked at the bottom of lagoons, scooping up shrimp, worms and other small invertebrates from the mud. The species was likely a poor swimmer, unable to go after more capable prey.

"It wouldn't survive in the modern world, but it didn't have any rivals at the time," Motani said.

Like the modern day platypus, researchers think Eretmorhipis carrolldongi's bill housed a collection of mechanoreceptors, which helped it locate dinner.

Researchers described the unusual species in the journal Scientific Reports.

"The specimens represent the oldest record of amniotes with extremely reduced visual capacity, utilizing non-visual cues for prey detection," scientists wrote. "The discovery reveals that the ecological diversity of marine predators was already high in the late Early Triassic."