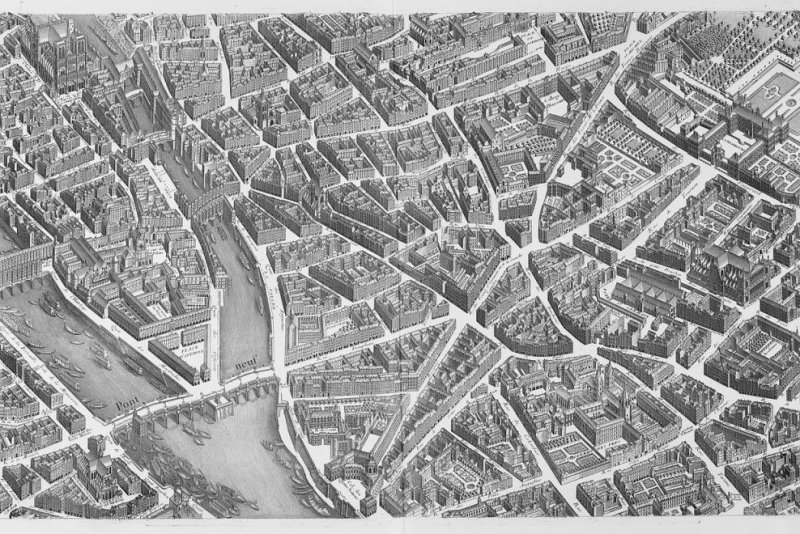

New research showed people who were better at memorizing the layout of a virtual city were also better at identifying smells. Photo by

Pixabay/CC

Oct. 19 (UPI) -- People with good spatial memory are better at identifying smells than those with poor navigational skills.

The link makes sense, researchers at McGill University argue, because animals evolved a keen sense of smell to aid navigation. Most animals rely on their olfactory system to track down food. Smells also help some animals find mates.

However, for modern humans, the olfactory system is much less important that it was for human ancestors and distant relatives. Scientists were skeptical that they could confirm a correlation.

Researchers designed a series of experiments to test participants' spatial memory and sense of smell. In one test, participants explored a virtual city, trekking down each street and passing by the city's 20 landmarks. Afterwards, participants were quizzed about the fastest routes between different landmarks. In a second test, participants were asked to identify different smells.

After completing the tests, participants allowed scientists to image their brains. The structural MRI results showed participants who performed better on both tests had a larger right hippocampus and a thicker medial orbitofrontal cortex, or mOFC.

Previous studies suggest the right hippocampus controls long-term memory, while the mOFC is essential to the olfactory system.

"We weren't sure, going in, that we would find that people who were better at identifying smells would also be good at navigating," Louisa Dahmani, now a postdoctoral researcher at Harvard University, said in a news release. "So the results came as a real surprise."

In a separate experiment, scientists recruited participants who had experienced a brain injury that damaged the medial orbitofrontal cortex. Tests showed the brain injuries resulted in diminished olfactory and spatial memory performance.

The study -- published this week in the journal Nature Communications -- is the first to link the medial orbitofrontal cortex to spatial memory.

"The fact that both functions seem to rely on similar brain regions supports the idea that they were systems in the brain that were evolving at the same time -- though this is theory, rather than anything we set out to show in this paper," said senior study author Véronique Bohbot. "All we can say for sure is that we now know a bit more about the brain systems involved in both navigation and olfaction."