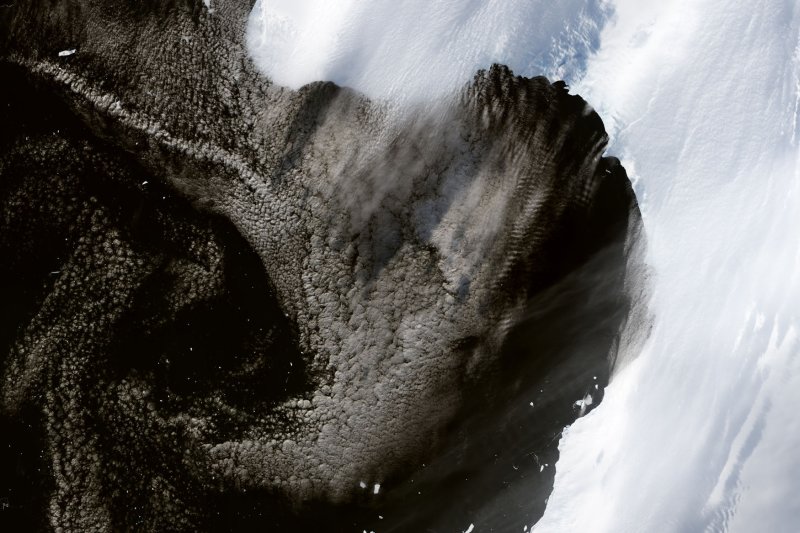

An ocean circulation pattern beginning near Antarctica helped flush more CO2 from the Pacific during the last period of deglaciation on Earth. Photo by NASA/UPI |

License Photo

Aug. 13 (UPI) -- The end of the last ice age was accompanied by a significant rise in the amount of carbon dioxide in Earth's atmosphere.

Scientists have long surmised the influx of CO2 originated in Earth's oceans, but the latest study is one of the first to show how and why large amounts of CO2 moved out of the Pacific and into the atmosphere.

According to the study, published this week in the journal Nature Geoscience, an acceleration of water circulation patterns in the Pacific, beginning near Antarctica, triggered the "flushing" of CO2 out of the deep sea.

Researchers worry a similar development could exacerbate manmade global warming.

"The Pacific Ocean is big and you can store a lot of stuff down there -- it's kind of like grandma's root cellar -- stuff accumulates there and sometimes doesn't get cleaned out," Alan Mix, an oceanographer at Oregon State University, said in a news release. "We've known that CO2 in the atmosphere went up and down in the past, we know that it was part of big climate changes, and we thought it came out of the deep ocean."

"But it has not been clear how the carbon actually got out of the ocean to cause the CO2 rise," Mix said.

Researchers gained an improved understanding of water circulation patterns by analyzing neodymium isotopes in ancient sediment cores. The data revealed the shifting speeds of a deep sea circulation pattern moving water from the Antarctic to Alaska and back.

The deep sea current begins in nearly Antarctic waters, carrying water slowly northward to Alaska before looping back to Antarctica and pushing deep ocean water toward the surface. Changes in neodymium isotope ratios showed the circulation pattern slowed during ice ages and sped up during periods of deglaciation.

Faster currents, scientists determined, pushed more deep ocean water to the surface, where CO2 was more easily released into the atmosphere, warming Earth's climate.

"It happened roughly in two steps during the last deglaciation -- an initial phase from 18,000 to 15,000 years ago, when CO2 rose by about 50 parts per million, and a second pulse later added another 30 parts per million," said Jianghui Du, a doctoral student in oceanography at Oregon State.

The findings are a reminder that the ocean alone can be a powerful driver of climate change.

Like forests, oceans have absorbed significant amounts of excess carbon emitted by fossil fuels. But just like forests, there is no guarantee that oceans will remain carbon sinks in perpetuity.

"If the ocean stops absorbing the excess CO2, and instead releases more from the deep sea, that spells trouble," Mix said. "Ocean release would subtract from our remaining emissions budget and that means we're going to have to get our emissions down a heck of a lot faster. We need to figure out how much."