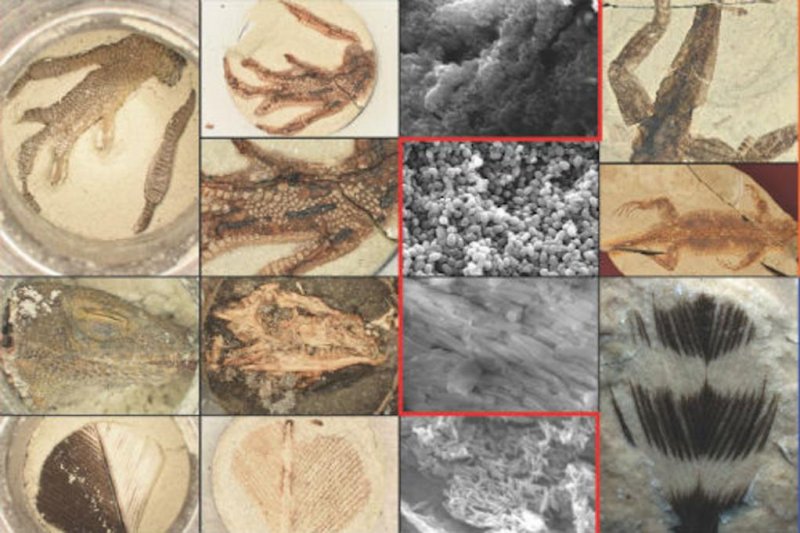

Scientists compared the synthetic fossils created in the lab with similar fossils found in the ground. Photo by Nicholas Edwards and Wang Yuan/University of Bristol

July 25 (UPI) -- Scientists have found a better way to accelerate the fossilization process in the lab. The new methodology promises to produce more realistic synthetic fossils, useful for comparisons with the real thing.

Usually, the process of fossilization takes thousands, if not millions, of years. But scientists have developed a new and improved way to replicate the heat, pressure and chemical reactions that result from millennia spent underground.

To speed up geologic time in the lab, Evan Saitta, a paleontologist with the Field Museum and the University of Bristol, and his research partner Tom Kaye, from the Foundation for Scientific Advancement, took bits of modern bird, lizard and plant samples and packed them into tiny clay tablets with a hydraulic press.

The duo then placed the tablets in a sealed metal tube inside an oven, subjecting them to 410 degrees Fahrenheit and 3,500 psi pressure. After 24 hours, they retrieved the tablets and analyzed the plant and animal remains.

"We were absolutely thrilled," Saitta said in a news release, speaking of the results. "We kept arguing over who would get to split open the tablets to reveal the specimens. They looked like real fossils -- there were dark films of skin and scales, the bones became browned. Even by eye, they looked right."

Previous attempts to replicate the fossilization process have mostly relied on small, sealed chambers that not only trap in the organic molecules of interest, but the decaying byproducts of less stable molecules. The presence of these particles, which would never survive the real fossilization process, interfere with the ability of scientists to compare synthetic and natural fossil for scientific purposes.

Kaye helped Saitta develop a process that would allow volatile degradation products to escape. They duo realized the missing element was sediment. By embedding the material in clay, they were able to offer an escape route for the interfering particles.

"The sediment acts as a filter allowing unstable molecules to escape from the sample, revealing browned, flattened bones surrounded by dark, organic films where soft tissues once were," Saiita said in a University of Bristol news release.

Researchers believe their technology -- detailed this week in the journal Paleontology -- will allow scientists to test their hypothesis about the survivability of and effects of decay on different types of plant and animal material.