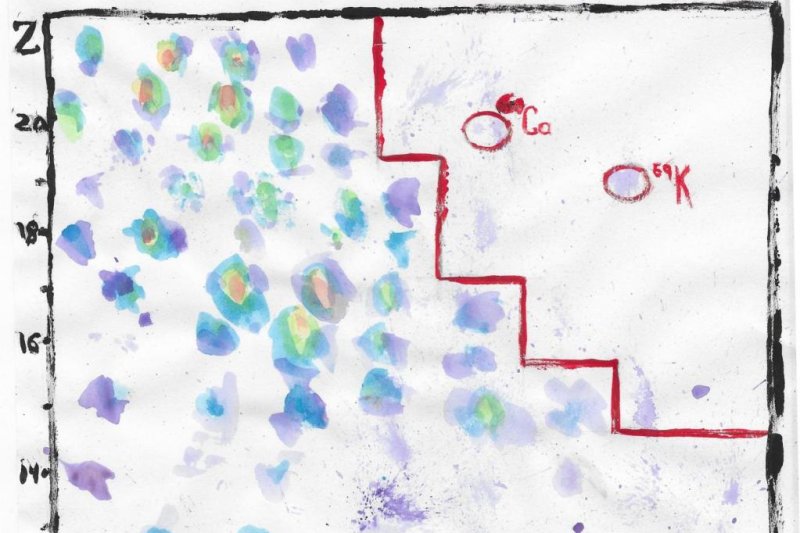

Ninth-grader Alexandra Tarasova used watercolors to interpret the exotic isotope yielded by the latest RIBF experiments. Photo by Alexandra Tarasova/Holt High School

July 12 (UPI) -- Scientists have discovered eight new isotopes -- all of them the heaviest-known forms of their respective elements.

Through experimentation at RIKEN's Radioactive Isotope Beam Factory in Japan, scientists synthesized new sulfur, chlorine, argon, potassium, scandium and calcium isotopes -- each with record numbers of neutrons.

All iterations of an atomic element feature the same amount of protons, but different isotopes feature different numbers of neutrons in the nucleus. The more neutrons an atom has, the heavier it is.

The makeup of an atom's nucleus can affect its properties, particularly it's half-life -- or how quickly the atom decays. Stable isotopes can live forever, but some heavy isotopes flash in and out of existence in a matter of seconds.

Scientists discover new isotopes by using powerful particle accelerators to slam zinc particles onto a block of beryllium. The collisions can yield a variety of unexpected atomic byproducts.

The eight new byproducts identified during the most recent RIBF experiments were detailed this week in the journal Physical Review Letters.

By finding and studying the behavior of different isotopes, scientists can improve their understanding of the nuclear force -- the force that binds protons and neutrons together.

Until the latest experiments, calcium-48 was the heaviest-known calcium isotope. But researchers were able to synthesize two new isotopes, calcium-59 and calcium-60. The most stable version of calcium can live for hundreds of quintillion years -- 40 trillion times the age of the universe. Calcium-60 lasts just a few thousandths of a second before it disintegrates.

By observing exotic isotopes and their peculiarities, scientists can improve their models of the nuclear force.

"Some of these models that describe nuclei at the highest resolution scale predict that 20 protons and 40 neutrons will not hold together to form Ca-60," Alexandra Gade, professor of physics at Michigan State University, said in a news release. "The discovery of calcium-60 will prompt theorists to identify missing ingredients in their models."