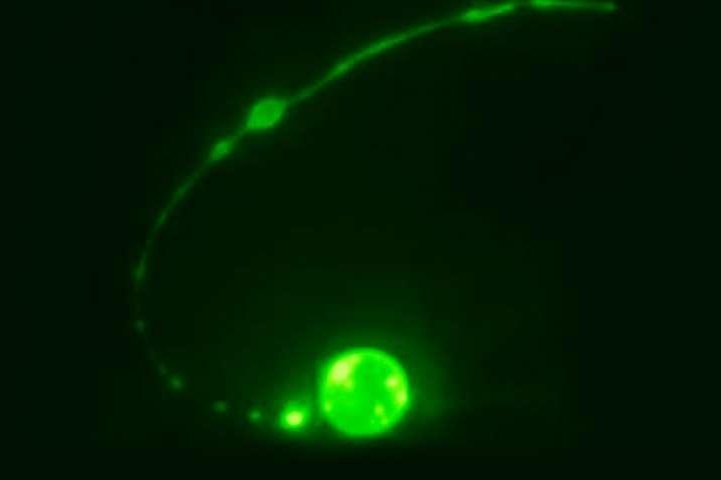

An image shows the core of a tail spike cell rounding up prior to being disintegrated. Photo by Laboratory of Developmental Genetics/Rockefeller University

March 19 (UPI) -- For the human cell, the process of dying is surprisingly complex. New research into the process has offered scientists insights into what happens to dead cell fragments.

Like almost all cellular processes, if the process of cell death malfunctions, health maladies can occur. To better understand how cells die -- and how glitches in the process might impact humans -- researchers at Rockefeller University studied an unusually shaped cell, called a tail spike cell, in C. elegans, a microscopic worm.

When cells die, other cells must descend on the retired cellular corpse to process the remains, or clear away the debris. If the leftovers are left to linger, disease and development problems can arise. Some cells are easier to process than others. Some neurons boast complex structures that aren't easy to breakdown.

Tail spike cells help C. elegans form its tail. Once it's developmental mission is complete, it dies. When researchers watched the worm species break down its dead tail spike cells, they were surprised to witness a recycling process unlike most they've witnessed before.

"Curiously, the middle of the cell is spliced out first," postdoctoral fellow Piya Ghose said in a news release.

The process begins with the separation of the cell's core from the rest of the structure, which rounds itself up and disintegrates. Next, the remaining cellular shell splits in two and is processed via two different mechanisms.

"The part of the extension closest to the cell body is broken up into bead-shaped bits, while the distal part retracts into a ball, which is then removed by a neighboring cell," Ghose said.

Interestingly, scientists observed a similar pattern of cell death and disintegration among the worm's neurons.

"Since we see this phenomenon in two different cell types with complicated shapes, it is conceivable that similar death events occur in many animals, and perhaps even in human disease," said lead researcher Shai Shaham.

During the analysis of cell death, scientists also found phagocytes, the cells responsible for vacuuming up the deceased cell debris, use the protein EFF-1 to help grab and gobble up tiny cellular fragments.

The findings, published this week in the journal Nature Cell Biology, set the stage for further exploration of a little understood system.

"There is a lot we don't understand about this remarkable death process, and we are hot on the trail of additional players," Shaham said.