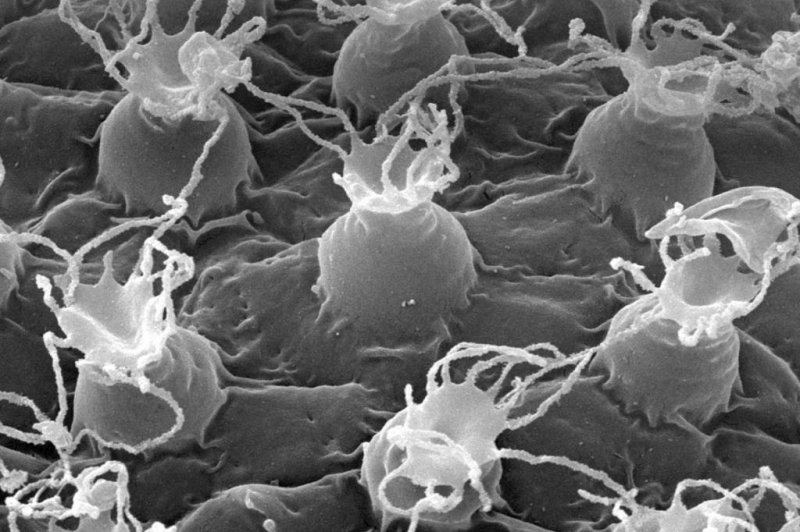

The newly discovered tardigrade species lays eggs with tentacle like tendrils. Photo by Stec et al./PLOS One

March 1 (UPI) -- Just when you thought tardigrades couldn't get any weirder, scientists discover an algae-eating water bear that lays tentacled eggs.

Tardigrades are the eight-legged micro-animals that appear both adorable and freakish, and have earned a reputation as the toughest animals on planet Earth.

Kazuharu Arakawa, a molecular biologist at Japan's Keio University, found the new tardigrade species in a moss sample he pulled from the parking lot outside his apartment. As most new water bear species are found in bits of moss and lichen, those who make a living studying tardigrades are always on the lookout for a fresh and interesting patch of the spongy, green plants.

When Arakawa sequenced the genome of the tardigrade living in the moss sample, he could find no match for it in the existing database. Believing that he's located a new species, he got in touch with fellow tardigradologist Łukasz Michalczyk of Jagiellonian University in Poland.

Michalczyk and his colleagues confirmed Arakawa's suspicion. The specimen warranted a new species classification -- they named it Macrobiotus shonaicus.

Water bears are incredibly resilient. They can be dehydrated and then resuscitated years later with a drop of water. They can survive extreme heat. They can even be frozen and thawed, exposed to radiation and sent to space and back, each time springing back to life.

Macrobiotus shonaicus looks a lot like other water bears, with a puffy, caterpillar-like body and a tiny mouth composed of three ringed rows of teeth.

The eggs laid by Macrobiotus shonaicus are what makes the new species unique. They look like upside-down octopi, with wily tendrils waving about.

The species' eating habits also make it unusual. While most water bears are carnivorous, subsisting on animals that are even smaller than they are, the new species can subsist on algae.

Outside of genetic analysis, the best way to tell the hundreds of tardigrade species apart is by studying their egg morphology. Scientists aren't quite sure the micro-animals lay such wide variety of egg types.

"It could be hypothesized that different egg morphotypes are adaptations to egg laying in specific microhabitats that require different shapes and sizes of egg processes," Daniel Stec, a researcher at Jagiellonian, said in an interview.

But Stec -- lead author of the new study describing the species in the journal PLOS One -- suggests it's also possible that water bears are so resilient and successful, evolutionarily speaking, they have a greater freedom to experiment.

"If this alternative scenario was true, it would mean that relaxed natural selection allows departures from ancestral egg morphotype and results in such a great diversity of egg ornamentation," Stec said. "Nevertheless, it remains to be tested which of these is a true explanation."

Though researchers say tardigrades have largely become an Internet sensation thanks to their strange cuteness, scientists are mostly interested in their unique resilience. Analysis of their ability to withstand long periods of dehydration helped scientists design longer-lasting vaccines.

"Maybe someday, thanks to tardigrades, we will be able to preserve organs for transplantation, extend our lifespan, or travel to other planets and stars, not worrying about detrimental effects of cosmic radiation," Stec said.