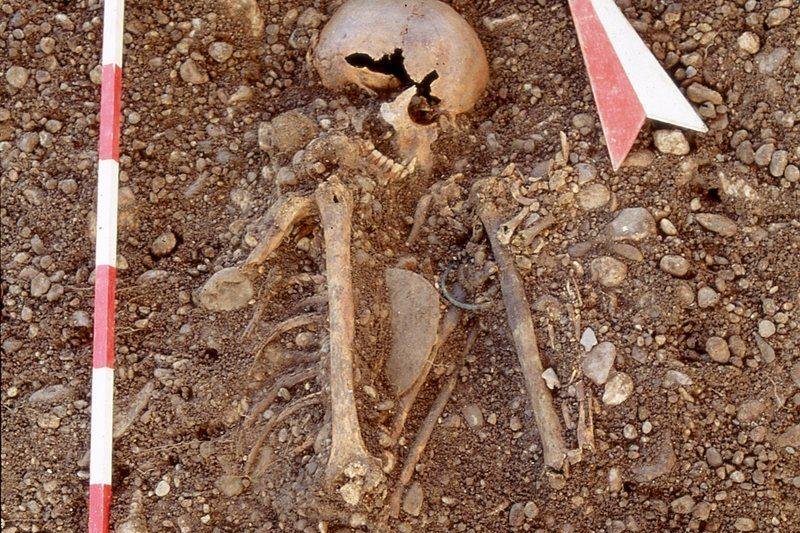

Scientists found the genome of the plague bacterium among human remains from the Stone Age. Photo by Stadtarchäologie Augsburg/MPG

Nov. 22 (UPI) -- The earliest evidence of the plague-causing bacterium Yersinia pestis suggests the disease first arrived in Europe during the Stone Age, several millennia before the first documented epidemics.

According to analysis by researchers at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, the bacteria was carried to Central Europe by wave migrations of steppe nomads arriving between 4,800 to 3,700 years ago.

Scientists detailed their discovery this week in the journal Current Biology.

Researchers surveyed more than 500 tooth and bone samples collected from Germany, Russia, Hungary, Croatia, Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia. Their analysis yielded six instances of the Yersinia pestis genome.

These bacteria strains that caused these early infections were closely related.

"This suggests that the plague either entered Europe multiple times during this period from the same reservoir, or entered once in the Stone Age and remained there," researcher Aida Andrades Valtueña said in a news release.

Roughly 4,800 years ago, people of the Caspian-Pontic Steppe began to move into Europe. The genetic signatures of their arrival are present in almost all modern Europeans. These signatures can be traced to reveal specific waves of migration.

The latest analysis suggests the arrival of Yersinia pestis coincides with the expansion of Caspian-Pontic Steppe populations into Europe.

"In our view, the human genetic ancestry and admixture, in combination with the temporal series within the Late Neolithic-Bronze Age Y. pestis lineage, support the view that Y. pestis was possibly introduced to Europe from the steppe around 4,800 years ago, where it established a local reservoir before moving back towards Central Eurasia," said researcher Alexander Herbig.

The new research also confirmed that the plague bacteria was undergoing genetic mutations related to its virulence at the time of its arrival.

Some have suggested the bacteria didn't evolve the ability to cause significant outbreaks until a few thousand years later, but it's possible the bacteria was already potent enough to trigger epidemics during the Stone Age.

"The threat of Y. pestis infections may have been one of the causes for the increased mobility during the late Neolithic-early Bronze Age period," said Johannes Krause, director of the Department of Archaeogenetics at MPG.

The arrival of the plague bacteria during the Stone Age could have triggered genetic turnover among European populations.

"It's possible that certain European populations, or the steppe people, may have had a different level of immunity," Krause said.

Further analysis of Y. pestis genomic samples is needed to unravel the detailed history and evolution of the deadly disease and its effects on human evolution.